Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

Hello, First National Bank? This is Laura. I need to transfer all my funds before my wife, I mean husband, finds out. (Saddboy, CC-BY-SA 3.0)

I spent some time in Seattle recently, and ran across an article in a neighborhood newspaper, the Queen Anne & Magnolia News, about transgender activists trying to enable abusive exes:

Duff, a contract caregiver, said she’d banked at the Magnolia branch (3300 W. McGraw St.) for more than two years before changing her name and gender marker last September.

Duff said she’d provided the bank updates [sic] copies of her new driver’s license and updated photo. But when she called in for an update on her account balance, she ran into new issues.

The bank representative, according to Duff, asked her multiple security questions, all of which she answered correctly. Despite that, Duff said, she was placed on hold so that she could be forwarded to a manager.

“That hold became a permanent hold,” Duff said.

Duff called back and was told that the bank wouldn’t provide any information over the phone because the account was listed as Lizzi Duff, female.

“I said, ‘That’s me: Lizzi Duff, female,’” Duff said. “Me answering all my security questions should prove that it’s me.”

Duff claims the bank representative hung up on her and that she called back a third time, only to go through another half-dozen security questions. She said she was finally allowed to access her account after relaying her driver’s license number.

This wasn’t a matter of a woman with a low voice register. The bank operator recognized a male voice trying to access an account marked as a woman’s, bypassing the way most people access their accounts today. The operator was right! It was a man’s voice.

That, however, is not what drew me to write about the story. The transgender activists rallying around Duff believe that critical security procedures are an attack on transgender people:

Duff believes the employee profiled her voice as a man’s, which is why so many additional security questions were asked.

“Voice profiling is a common and a really hateful way of discriminating against transgender people and attacking our right to be on the planet,” she said.

Looking for discrepancies between the person asking for account info and the person on file is not an attack. It is critical security.

Duff does not want to identify as transgender, but as female. Duff also chose to handle bank transactions with a human rather than using a password or PIN at a computer or ATM. Computers and ATMs don’t care what a person sounds like, only what they type—because passwords truly are secret information. Calling in is automatically going to increase the chance of scrutiny because it is an indication that the caller does not know the password—and thus might not be the account owner.

Frankly, the bank operator should not have hung up. If they think someone is trying to access someone else’s account, they should bring in the authorities, not just hang up. But, I don’t know how many phone calls they receive every day like that. And I do know from experience that they don’t do this, because this is not a made-up concern. I know someone who was told that a man had tried to gain access to her account. In her case, he tried to lie that they were still together, but if you allow the ex to just say they are the person they are trying to swindle, then their job becomes a lot easier.

Ignoring vocal discrepancies when someone calls in to a human operator rather than using their password or PIN at a computer or ATM would be a great boon for abusive ex-boyfriends and ex-husbands, who already know most, if not all, of the other identifying information of their victims. A driver’s license number is not, and should not be considered, enough to identify a person over the phone. The people most likely to bear a grudge against a woman are the people most likely to know that kind of identifying information.

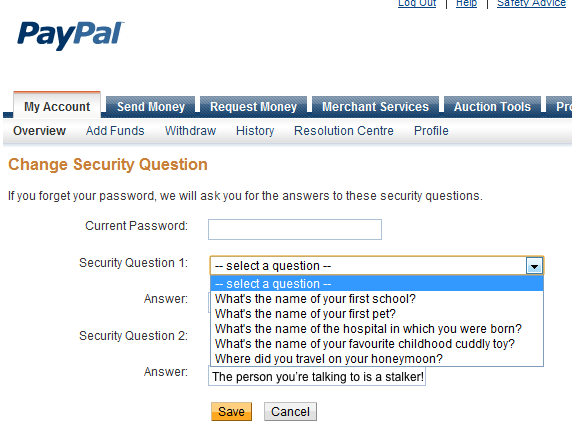

This is the critical flaw in password insecurity questions; they allow bypassing passwords through non-secret information. Password insecurity questions have at least the justification of being meant for use only for computer-automated password recovery; computers can’t do the kind of common-sense pattern matching that a human can.1 We must not force human bank operators to ignore their own common sense with the result that our bank account passwords become as easy to bypass as Yahoo mail.

- April 27, 2016: Insecurity Questions enable harassment and abuse

-

I bet they’d still let them in if the stalker called with a good sob story about being stalked.

I complain a lot about insecurity questions in other articles about organizations wanting to rely solely on them and not on human intelligence. For example, wanting banks to ignore that the person owning the account is listed as a woman but the voice is clearly a man’s.

The reason insecurity questions suck so much is that they don’t just enable hackers to persecute us. Most of us live in the serene knowledge that we are too inconsequential to matter to hackers, and even when hackers randomly choose one person to steal money from, we’re still just one in three hundred million in the United States, and one in seven billion in the world. The odds, we think, are in our favor.1

Insecurity questions suck because they enable easy hacking by precisely the people we do have to worry about: the abusive ex-boyfriend, the crazy ex-girlfriend with a penchant for boiling rabbits, the stalker, the shady brother-in-law who is always in debt. Insecurity questions rely on personal information that are already known by the people we most have to worry about. Even those answers that are not widely known among our acquaintances are easily knowable simply by engaging in normal conversation among our web of friends. And the people you have to worry about have access to the edges of your web of friends. All they have to do is innocently start talking about high school to someone they know went to high school with you, and they’ve got your high school. Your pet’s name probably has already been posted to Facebook and is easily accessible by a friend of a friend who is not your friend at all.

The entire reason for insecurity questions is so that someone who does not have your password can reset your password without having to talk to a human. The selling point is that they are for helping you when you don’t have your password. But they’re just as useful for anyone else who also doesn’t have your password.

- January 22, 2016: Should Apple enable exes to access their ex-spouse’s iPad?

-

“Hey, Apple, give me a second. Yup, now she’s dead.” (Saddboy, CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Chris Matyszczyk complains that Apple wouldn’t give a woman the password to her dead husband’s iPad, even though all she wanted to do was play card games on it.

“Even showing the company his death certificate”, reads the summary, did no good in getting his Apple ID password.

But she didn’t show his death certificate. She showed a copy of his death certificate.1 It’s a document that is easily forged, and, for that matter, varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. There is no way for a company in Cupertino to know what a valid death certificate in British Columbia is supposed to look like or how to verify that it’s real.

Imagine this scenario:

A man calls Apple and says that his wife recently died. He provides a copy of her death certificate and a copy of her will, and then uses this to access the iPad he stole from his ex-wife—who is not dead after all—and use her contacts list and passwords list to harass her both socially and financially, eventually driving her to poverty and death.

Apple would be excoriated, justifiably so, for having relied on such easily forged documents.2

Matyszczyk writes in the article that:

Those blessed with common sense might wonder that digital assets are no different from any other possessions. If you bequeath your things to someone else, that person should have the automatic rights to those things.

I am not familiar with Canada, but in the United States, we do in fact require courts to be involved with the distribution of physical assets after a death. That’s what an executor is for, to act as a liaison between the probate court system and the inheritors. It isn’t “extreme” for Apple to want a court to be involved in the official transfer of assets after death. It is the normal process. Apple should be wary of anyone asking them to bypass the normal process. That’s a sign that this could be a social engineering attack.

This is a horrible rationale, because computer-automated password recovery is practically designed to aide hackers, but at least the logic makes sense.

↑

- Transgender community rallies behind Magnolia resident: Eric Mandel

- “Voice profiling is a common and a really hateful way of discriminating against transgender people and attacking our right to be on the planet,” she said.

More banking

- Insecurity questions on phones and at banks

- How important are the last four digits of your social security number? That and a high school yearbook can get a hacker your bank account.

More identity theft

- Insecurity Questions enable harassment and abuse

- Insecurity questions are designed specifically to let someone who does not have your password access your account without having to talk to a human. The idea is that that person will be you after you forget your password, but the computer does not care. Anyone or anything with that information can access your account.

- Should Apple enable exes to access their ex-spouse’s iPad?

- Chris Matyszczyk wants Apple to just believe someone who says their spouse died, and give access to their iPad, then claims that this is how everything else, from house titles to bank accounts work. Unfortunately, he’s not far off there.

More insecurity questions

- Security is hard, and 2FA is not the answer

- Is 2-factor authentication the magic bullet in security? Not unless we solve the real problem, which is that people always take the easy way out—and that includes service providers.

- Security questions will always be insecure

- Insecurity questions are insecure because their purpose is to allow access to someone who does not know the access credentials. This trait is shared by zero or one person who has forgotten their password, and an infinitude of people who never knew it in the first place—because they shouldn’t have access.

- Are insecurity questions designed to help hackers?

- Insecurity questions are being modified to make them easier to hack and harder to remember. It’s as if they’re designed to help hackers and frustrate forgetful account owners.

- Insecurity Questions enable harassment and abuse

- Insecurity questions are designed specifically to let someone who does not have your password access your account without having to talk to a human. The idea is that that person will be you after you forget your password, but the computer does not care. Anyone or anything with that information can access your account.

- Mat Honan should read Mimsy

- “Because the last four numbers of your SSN are what businesses ask for, they are all that a criminal sometimes needs to use your cash or credit.”

- Two more pages with the topic insecurity questions, and other related pages

More passwords

- Security is hard, and 2FA is not the answer

- Is 2-factor authentication the magic bullet in security? Not unless we solve the real problem, which is that people always take the easy way out—and that includes service providers.

- Security questions will always be insecure

- Insecurity questions are insecure because their purpose is to allow access to someone who does not know the access credentials. This trait is shared by zero or one person who has forgotten their password, and an infinitude of people who never knew it in the first place—because they shouldn’t have access.

- Insecurity questions on phones and at banks

- How important are the last four digits of your social security number? That and a high school yearbook can get a hacker your bank account.

- The most popular passwords at school

- We are still lying about passwords to our community. What are the most popular first words in passwords?

- Embarrassing password tricks

- Never trust anyone over 30 characters.

More social engineering

- Security is hard, and 2FA is not the answer

- Is 2-factor authentication the magic bullet in security? Not unless we solve the real problem, which is that people always take the easy way out—and that includes service providers.

- How does Apple’s supposed anti-conservative bias matter?

- If you think Apple has a bias against conservatives or Christians, you definitely don’t want Apple to build a tool its employees can use to help guess an iPhone’s password.

More transphobia

- The Destruction of Title IX

- If you put the government in charge of a desert, in fifty years you’ll have a shortage of sand. If you put the government in charge of protecting women, in fifty years you’ll have government-sponsored violence against women.

- That’s a man, baby: Your fantasy is hurting people

- We are beating and mutilating children in the name of tolerance. There will come a time when our denial of biological reality is recognized as a mass hysteria, when child castration is recognized as the barbarity that it is.

- How the left transformed vulgarity into courage and elected Donald Trump

- When you lose to Donald Trump, look inward, because it isn’t Donald Trump’s fault. The establishment left, especially the media, attacked Donald Trump just like he was Joe the Plumber. But Donald Trump has the platform to attack back. Doing so took courage, and the Plumbers of America recognized that.

- Dr. Frank N. Furter: the left’s answer to transgender bathrooms

- The left thinks transgenders are murderous, cannialistic rapists. And they approve.

- Nothing to Queer but Queer itself

- You’re just being paranoid, America. Nobody’s forcing you to take part in gay marriage or forcing your children to approve of transsexuality. Just let them be themselves and they’ll leave you alone.

- Two more pages with the topic transphobia, and other related pages

More vulnerable

- Money Changes Everything: Empowering the vicious

- Barbarism empowers the rich, the powerful, the vicious, the strong. Civilization empowers everyone else. Gun control and centralized economies, darlings of the progressive left, have empowered the vicious since the beginning of time. The beltway crowd prefers no competition from people free to barter, or free to defend themselves.

- Handmaid’s Tale experiences backlash over handling of religion

- Fans of Margaret Atwood’s new television show turn against the series after revelations the story is a metaphor for Islam’s treatment of women.

- But the rhetoric’s so much better here under the tragedy!

- Want to stop domestic terrorism? Take seriously those who say they want to kill. Want to stop the oppression of women and the gay community? Take seriously those who say they want to literally enslave women and kill gays.

- Insecurity Questions enable harassment and abuse

- Insecurity questions are designed specifically to let someone who does not have your password access your account without having to talk to a human. The idea is that that person will be you after you forget your password, but the computer does not care. Anyone or anything with that information can access your account.