The pseudo-scientific state and other evils

When I was growing up, much of my reading library was my dad’s large collection of westerns and mysteries. I read a lot of Ellery Queen, Erle Stanley Gardner and other mysteries of the era, as well as the occasional G.K. Chesterton Father Brown story in a best of collection.

Lately I’ve been using Project Gutenberg to keep iBooks filled with waiting-for-others reading, and pulled down some Father Brown collections. While browsing through Chesterton’s work, I discovered he also had essay collections, so I added a few of those as well.

Sunday morning, I started reading Eugenics and Other Evils and was hooked right from the introduction:

Though most of the conclusions, especially towards the end, are conceived with reference to recent events, the actual bulk of preliminary notes about the science of Eugenics were written before the war. It was a time when this theme was the topic of the hour; when eugenic babies (not visibly very distinguishable from other babies) sprawled all over the illustrated papers; when the evolutionary fancy of Nietzsche was the new cry among the intellectuals; and when Mr. Bernard Shaw and others were considering the idea that to breed a man like a cart-horse was the true way to attain that higher civilisation, of intellectual magnanimity and sympathetic insight, which may be found in cart-horses. It may therefore appear that I took the opinion too controversially, and it seems to me that I sometimes took it too seriously. But the criticism of Eugenics soon expanded of itself into a more general criticism of a modern craze for scientific officialism and strict social organisation.

And then the hour came when I felt, not without relief, that I might well fling all my notes into the fire. The fire was a very big one, and was burning up bigger things than such pedantic quackeries. And, anyhow, the issue itself was being settled in a very different style. Scientific officialism and organisation in the State which had specialised in them, had gone to war with the older culture of Christendom. Either Prussianism would win and the protest would be hopeless, or Prussianism would lose and the protest would be needless. As the war advanced from poison gas to piracy against neutrals, it grew more and more plain that the scientifically organised State was not increasing in popularity. Whatever happened, no Englishmen would ever again go nosing round the stinks of that low laboratory. So I thought all I had written irrelevant, and put it out of my mind.

I am greatly grieved to say that it is not irrelevant. It has gradually grown apparent, to my astounded gaze, that the ruling classes in England are still proceeding on the assumption that Prussia is a pattern for the whole world. If parts of my book are nearly nine years old, most of their principles and proceedings are a great deal older. They can offer us nothing but the same stuffy science, the same bullying bureaucracy and the same terrorism by tenth-rate professors that have led the German Empire to its recent conspicuous triumph. For that reason, three years after the war with Prussia, I collect and publish these papers.

He wrote this in 1922, so his “war with Prussia” was what we would call the First World War. He of course didn’t call it that, being as the Second had not yet happened.

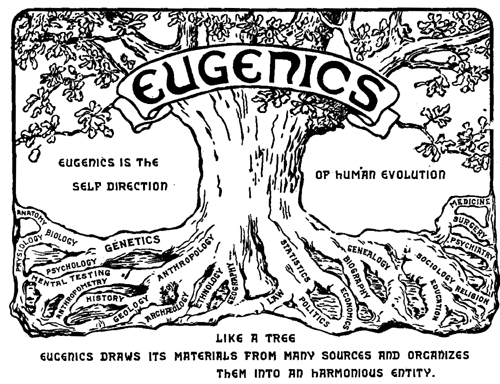

In his “and other evils”, Chesterton appears to expand the term eugenics too a much wider definition than what we usually mean. It encompasses a lot of the so-called “scientific state”, that is, a state modeled around controlling people’s lives according to scientific principles that will make them more useful to the state.

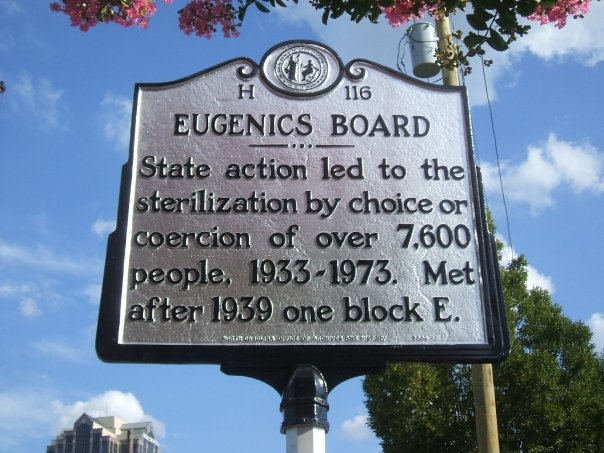

For a long time, World War II and the Nazis precluded any fears of the state organizing society along such pseudo-scientific principles; while many of the trappings of the scientific state remained, such as Margaret Sanger’s project to weed out black babies and the minimum wage’s pricing unskilled workers out of the market, they were unmoored from their eugenicist docks.

But now today this grievous ideal is taking root again among our elite.1 You could take those last two paragraphs and replace Prussia with China and make it relevant yet again, nearly a hundred years later.

His first chapter goes on to describe what he means by eugenics, which is notable especially for its intro on the spread of evil:

I know that [Eugenics] means very different things to different people; but that is only because evil always takes advantage of ambiguity. I know it is praised with high professions of idealism and benevolence; with silver-tongued rhetoric about purer motherhood and a happier posterity. But that is only because evil is always flattered, as the Furies were called “The Gracious Ones.” I know that it numbers many disciples whose intentions are entirely innocent and humane; and who would be sincerely astonished at my describing it as I do. But that is only because evil always wins through the strength of its splendid dupes; and there has in all ages been a disastrous alliance between abnormal innocence and abnormal sin.

Then he goes on to describe the various kinds of arguments in favor of eugenics, including those that say the law will only go so far as they leash it, so to speak, and no further:

I had thought of calling the next sort of superficial people the Idealists; but I think this implies a humility towards impersonal good they hardly show; so I call them the Autocrats. They are those who give us generally to understand that every modern reform will “work” all right, because they will be there to see. Where they will be, and for how long, they do not explain very clearly. I do not mind their looking forward to numberless lives in succession; for that is the shadow of a human or divine hope. But even a theosophist does not expect to be a vast number of people at once. And these people most certainly propose to be responsible for a whole movement after it has left their hands. Each man promises to be about a thousand policemen. If you ask them how this or that will work, they will answer, “Oh, I would certainly insist on this”; or “I would never go so far as that”; as if they could return to this earth and do what no ghost has ever done quite successfully—force men to forsake their sins. Of these it is enough to say that they do not understand the nature of a law any more than the nature of a dog. If you let loose a law, it will do as a dog does. It will obey its own nature, not yours. Such sense as you have put into the law (or the dog) will be fulfilled. But you will not be able to fulfil a fragment of anything you have forgotten to put into it.

The emphasis is mine; it is worth remembering for any law. A law will draw forth as interpreters everyone who thinks they can use the law for their purpose. It will thus go as far as its nature, not as far as yours. There is no “pass the law to see what is in it”. What is in it is, with certainty, what you will see, whether you read it or not.

- February 15, 2023: Our Cybernetic Future 2023: Entropy in Action

-

When I was growing up, a standard response taught by parents to young children was “sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me.”

I doubt parents still teach that. There are a lot of assumptions in that advice that are no longer safe, notably that it won’t be taken as a challenge. The assumption then was that verbal exchanges remained verbal exchanges. Nowadays the assumption is that knifing a fellow student in the back is merely standard schoolyard play.

That was seriously said by the West Side Left, back in 2021.

Teenagers have been having fights including fights involving knives for eons. We do not need police to address these situations by showing up to the scene & using a weapon against one of the teenagers.

Their logic in letting kids knife kids would be perfectly understandable to Norbert Wiener. Yes, young teenagers have engaged in deadly fights for eons. It was hard work bringing our culture out of the barbarism of child violence. But there is a growing contingent today that doesn’t just want to ignore that without work we get barbarism, they welcome the slide backward into barbarism, even to the point of supporting kids knifing kids.

Without work, entropy always wins.

In part one, I highlighted John G. Kemeny’s argument that the proper relationship between man and machine in the age of the computer is a collaborative one with man in control. In part two I examined Vannevar Bush’s prescient vision of a networked future in which scientific discoveries would be readily available to all, ensuring that science and technology would always advance to the benefit of mankind rather than being lost in dusty libraries. And in part three I added Norbert Wiener’s warnings that entropy applies to communications—especially networked communications—just as it applies to physics.

What can we learn from these three visionaries more than half a century on?

- December 14, 2022: Our Cybernetic Future 1954: Entropy and Anti-Entropy

-

Having dealt with someone at the far cusp of the personal computer revolution, and someone at its conception, I’d like to look at someone in between. Like Vannevar Bush1, Norbert Wiener• did not use personal computers. They didn’t exist. Nor was there anything remotely like the Internet. But it was the Internet’s potential for degrading human communication that frightened him. Or, more generally, the vast speed-up of the coming communications technology divorced from any acknowledgment that communication is always subject to degradation and that progress is not natural.

Norbert Wiener feared a faster and faster world with less and less content, because of a culture that more and more denies the existence of entropy. Entropy originated as a term from physics, for the level of disorder and randomness in a system. It’s the second law of thermodynamics, which, in simpler terms, means that everything tends toward disorder. Order requires that some form of work be added to the system. You can think of entropy as a measure of how jumbled up a jigsaw puzzle is. But the universe is not just a jigsaw puzzle that must be put back together—applying work to reduce the entropy in the puzzle. The universe is a jigsaw puzzle that continually falls apart, as if it were on a glass table in an earthquake. Work is required not just to keep it from getting more disordered, but to keep it from mixing up with the table, too.

Wiener published The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society in 1954. What Wiener wanted to bring to public attention was the meaning of life, communication, and being human in a world where communications and computers were speeding up just as Vannevar Bush had promised us they would. New forms of communication would soon connect far more people for far more uses than previously imaginable.

Norbert Wiener was one of the founders, if not the founder, of the field of Cybernetics. He defined Cybernetics as:

- November 30, 2022: Our Cybernetic Future 1945: As We May Blog

-

In 1945, Vannevar Bush told us our future: fast computers attached to powerful networks, enabling nearly unimaginable individual creativity and research; and even more importantly, communications both with other people and with the vast wealth of human knowledge. As We May Think is possibly the most influential essay in the history of both science fiction and computers. I’m almost surprised that we didn’t name computers “memexes” given how influential As We May Think was in science fact and fiction.

There are two aspects of this very famous and influential essay: what was happening, and what was going to happen, both the growth of knowledge and the advancement of computer science. Vannevar Bush didn’t use terminology we’re familiar with. It didn’t exist. The title of the essay was meant literally: he predicted that our thinking would change in the future. He predicted a hybrid, cyborg future, offloading repetitive thought to automated processes, and naturally integrating automated knowledge retrieval into the way we think on a daily basis.

As someone who can no longer remember anything without keeping my phone on hand, I resemble that vision.

“There is a growing mountain of research…” Bush wrote, and “we are being bogged down today as specialization extends…”. Important research had always run the risk of obscurity, and it was only getting worse.

Mendel’s concept of the laws of genetics was lost to the world for a generation because his publication did not reach the few who were capable of grasping and extending it; and this sort of catastrophe is undoubtedly being repeated all about us, as truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential.

- November 16, 2022: Our Cybernetic Future 1972: Man and Machine

-

I’m dividing my promised sequel to Future Snark into three parts, one each for three very smart views of a future that became our present. These are the anti-snark to that installment’s snark: Vannevar Bush (1945), Norbert Wiener (1954), and John G. Kemeny (1972). I was going to title it “Snark and Anti-Snark” to extend the Toffler joke• further than it ought to go. But these installments are not snark about failed predictions. These are futurists whose predictions were accompanied by important insights into the nature of man and computer, what computerization and computerized communications mean for our culture, and what responsibilities we have as consumers and citizens within a computerized and networked society.

These authors understood the relationship between man and computer, before the personal computer existed. Their predictions were sometimes strange, but their vision of how that relationship should be handled embodied important truths we must not forget. Their views of our cybernetic future focus heavily on not just the interaction between user and machine but on the relationship between computerization and humanity in general.

Surviving the ongoing computer and communications revolution requires understanding that relationship.

I’m going to handle these authors in reverse order, starting with John G. Kemeny. Kemeny published Man and the Computer in 1972. If Kemeny’s name sounds familiar, you might recognize “Kemeny and Kurtz” as the developers of the BASIC programming language. Much of this book, while it wasn’t designed as such, is an explanation of why BASIC is what it is—a unique programming language unmatched even today as an interactive dialogue between the user and the computer. Unlike most programming languages—including BASIC itself on modern computers—Kemeny’s BASIC didn’t require creating programs in order to get the computer to do stuff. The same commands that could be entered into a computer program could be typed directly to the computer with an immediate response.

- October 13, 2021: Future Snark

-

I’ve been reading a lot of books lately about the future of technology from the perspective of the previous century. Predicting the future is always difficult, of course, but two stood out for how well they recognized what the future would have to deal with. Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock is from the perspective of the sixties (it was published in 1970), and Cyberwar is from the perspective of the nineties.1

Both got the future badly wrong, despite usually seeing where the transformations would come from. I think the problem for any futurist is aptly summed up by Harlan D. Mills in his introduction to a 1978 book about programming:

Back in 1900 it was possible to foresee cars going 70 miles an hour, but the drivers were imagined as daredevils rather than grandmothers. — Harlan D. Mills (BASIC with style•)

Technology policies made by someone who cannot comprehend the future equivalent of 70 miles per hour will always be wrong. It is nearly impossible to jettison the spectacles through which we view the world. If you’ve rarely gone faster than walking speed2, the notion of seventy miles an hour is one of reckless abandon. Even if you were to foresee that this would be a casual speed—I drove 75 miles per hour today merely getting my groceries—your forecast would be one of a world gone mad.

Seventy-five miles an hour to buy groceries? What’s the damn hurry? It’s legal? Even grandmothers do it? You’re all going to die!

A person looking forward from 1900 might well realize that vehicles will have the capability to go over 70 miles per hour. Fewer will recognize that drivers will routinely go more than seventy miles an hour. Fewer yet will realize that advances in materials design will make such speeds reliable and that advances in technology will make control of such vehicles nearly automatic.

What they almost always miss is the adaptability of the human brain and body. That we will learn how to routinely manage such speeds and that our brains will not freeze at the sight of, say, vehicles passing by on the other side of the highway at relative speeds in excess of 150 miles an hour. That our reflexes will find shifting lanes at such speeds a normal task.

- December 19, 2018: Money Changes Everything: Empowering the vicious

-

Every once in a while you see someone take time out from promoting some form of government control of the economy and jump straight to saying money itself is bad, usually misquoting that money is the root of all evil. It’s important for them, because government controlled economies or exchanges eventually do destroy the value of money or the value of whatever is in the exchange. Which means they have to denigrate money or admit failure.

But money is not the root of evil. Money is the root of civilization. Money, instead of direct bartering, makes civilization possible by freeing up everybody who is neither rich nor powerful from day-to-day subsistence living.

Two of the oldest technological advances that progressives oppose are also the most empowering: guns and money. Like guns, money is something progressives claim to disdain but make sure they have access to themselves. And like guns, money makes life better for people with less power than the anointed. The beltway class can afford armed protection; they are often provided free armed protection by the state. That the invention of firearms makes effective self-defense available to everyone else, too, goes against every vision of the anointed.

Money is the same. It empowers everyone else to save, to buy, and to sell. Money, like guns, makes life safer and easier for the average person. It especially makes it easier for them to avoid becoming the prey of the rich, powerful, vicious, and strong.

Money is nothing more than a way to make bartering easier. If you want to trade for my time as a programmer, or for something at my yard sale, you don’t have to come up with something else that I want in order to barter in exchange for what you want. You give me money, and I will use it to get whatever I would have wanted in barter. I can wait until exactly the right thing comes along, without fear that what I have to sell will go stale, or be stolen. This further encourages sellers to create what people want. Money makes it easier for them to forego what is almost what they want, and wait or go elsewhere for better quality or better prices.

Where it always lay dormant, in their secret and not-so-secret fear that the Soviet scientific state would overwhelm our own free one.

↑

- Eugenics and Other Evils: G. K. Chesterton at Project Gutenberg (ebook)

-

“I know that [Eugenics] means very different things to different people; but that is only because evil always takes advantage of ambiguity. I know it is praised with high professions of idealism and benevolence; with silver-tongued rhetoric about purer motherhood and a happier posterity. But that is only because evil is always flattered, as the Furies were called ‘The Gracious Ones.’ I know that it numbers many disciples whose intentions are entirely innocent and humane; and who would be sincerely astonished at my describing it as I do. But that is only because evil always wins through the strength of its splendid dupes; and there has in all ages been a disastrous alliance between abnormal innocence and abnormal sin.”

“I know that [Eugenics] means very different things to different people; but that is only because evil always takes advantage of ambiguity. I know it is praised with high professions of idealism and benevolence; with silver-tongued rhetoric about purer motherhood and a happier posterity. But that is only because evil is always flattered, as the Furies were called ‘The Gracious Ones.’ I know that it numbers many disciples whose intentions are entirely innocent and humane; and who would be sincerely astonished at my describing it as I do. But that is only because evil always wins through the strength of its splendid dupes; and there has in all ages been a disastrous alliance between abnormal innocence and abnormal sin.”

- Liberal Fascism

- The story of how the National Socialist German Workers Party and the fascist government takeover of businesses became defined as a conservative movement by socialists and leftists who believe the government should control businesses.

- Murrow: His Life and Times

- Edward R. Murrow inspired generations of journalists with his reports from the London blitz on radio and, later, his reports on McCarthyism on television.

More eugenics

- Eugenics and Other Evils

- What’s old is new again: unwilling to learn the lessons of the past, those who wish to rule are returning to socialism and cronyism as the only two solutions for all the problems government creates. That is, more government to fix bad government.

- Liberal Fascism

- The story of how the National Socialist German Workers Party and the fascist government takeover of businesses became defined as a conservative movement by socialists and leftists who believe the government should control businesses.

More G. K. Chesterton

- Eugenics and Other Evils

- What’s old is new again: unwilling to learn the lessons of the past, those who wish to rule are returning to socialism and cronyism as the only two solutions for all the problems government creates. That is, more government to fix bad government.

More reigning in bad laws

- A one-hundred-percent rule for traffic laws

- Laws should be set at the point at which we are willing and able to jail 100% of offenders. We should not make laws we are unwilling to enforce, nor where we encourage lawbreaking.

- A free market in union representation

- Every monopoly is said to be special, that this monopoly is necessary. And yet every time, getting rid of the monopoly improves service, quality, and price. There is no reason for unions to be any different.

- Bipartisanship in the defense of big government

- We’ve got to protect our phony-baloney jobs. Despite their complaints about Trump’s overreach, Democrats have introduced legislation to make it harder for them to block his administration’s regulations.

- The Last Defense against Donald Trump?

- When you’ve dismantled every other defense, what’s left except the whining? The fact is, Democrats can easily defend against Trump over-using the power of the presidency. They don’t want to, because they want that power intact when they get someone in.

- The Sunset of the Vice President

- Rather than automatically sunsetting all laws (which I still support), perhaps the choice of which laws have not fulfilled their purpose should go to an elected official who otherwise has little in the way of official duties.

- 20 more pages with the topic reigning in bad laws, and other related pages