For a full month the business, for which I had returned to London, detained me there: and even then it was only the urgent advice of my physician that induced me to leave it unfinished and pay another visit to Elveston.

Arthur had written once or twice during the month; but in none of his letters was there any mention of Lady Muriel. Still, I did not augur ill from his silence: to me it looked like the natural action of a lover, who, even while his heart was singing “She is mine!”, would fear to paint his happiness in the cold phrases of a written letter, but would wait to tell it by word of mouth. “Yes,” I thought, “I am to hear his song of triumph from his own lips!”

The night I arrived we had much to say on other matters: and, tired with the journey, I went to bed early, leaving the happy secret still untold. Next day, however, as we chatted on over the remains of luncheon, I ventured to put the momentous question. “Well, old friend, you have told me nothing of Lady Muriel—nor when the happy day is to be?”

“The happy day,” Arthur said, looking unexpectedly grave, “is yet in the dim future. We need to know—or, rather, she needs to know me better. I know her sweet nature, thoroughly, by this time. But I dare not speak till I am sure that my love is returned.”

“Don’t wait too long!” I said gaily. “Faint heart never won fair lady!”

“It is ‘faint heart,’ perhaps. But really I dare not speak just yet.”

“But meanwhile,” I pleaded, “you are running a risk that perhaps you have not thought of. Some other man—”

“No,” said Arthur firmly. “She is heart-whole: I am sure of that. Yet, if she loves another better than me, so be it! I will not spoil her happiness. The secret shall die with me. But she is my first—and my only love!”

“That is all very beautiful sentiment,” I said, “but it is not practical. It is not like you.

- He either fears his fate too much,

- Or his desert is small,

- Who dares not put it to the touch,

- To win or lose it all.”

“I dare not ask the question whether there is another!” he said passionately. “It would break my heart to know it!”

“Yet is it wise to leave it unasked? You must not waste your life upon an ‘if’!”

“I tell you I dare not!”

“May I find it out for you?” I asked, with the freedom of an old friend.

“No, no!” he replied with a pained look. “I entreat you to say nothing. Let it wait.”

“As you please,” I said: and judged it best to say no more just then. “But this evening,” I thought, “I will call on the Earl. I may be able to see how the land lies, without so much as saying a word!”

It was a very hot afternoon—too hot to go for a walk or do anything—or else it wouldn’t have happened, I believe.

In the first place, I want to know—dear Child who reads this!—why Fairies should always be teaching us to do our duty, and lecturing us when we go wrong, and we should never teach them anything? You can’t mean to say that Fairies are never greedy, or selfish, or cross, or deceitful, because that would be nonsense, you know. Well then, don’t you think they might be all the better for a little lecturing and punishing now and then?

I really don’t see why it shouldn’t be tried, and I’m almost sure that, if you could only catch a Fairy, and put it in the corner, and give it nothing but bread and water for a day or two, you’d find it quite an improved character—it would take down its conceit a little, at all events.

The next question is, what is the best time for seeing Fairies? I believe I can tell you all about that.

The first rule is, that it must be a very hot day—that we may consider as settled: and you must be just a little sleepy—but not too sleepy to keep your eyes open, mind. Well, and you ought to feel a little—what one may call “fairyish “—the Scotch call it “eerie,” and perhaps that’s a prettier word; if you don’t know what it means, I’m afraid I can hardly explain it; you must wait till you meet a Fairy, and then you’ll know.

And the last rule is, that the crickets should not be chirping. I can’t stop to explain that: you must take it on trust for the present.

So, if all these things happen together, you have a good chance of seeing a Fairy—or at least a much better chance than if they didn’t.

The first thing I noticed, as I went lazily along through an open place in the wood, was a large Beetle lying struggling on its back, and I went down upon one knee to help the poor thing to its feet again. In some things, you know, you ca’n’t be quite sure what an insect would like: for instance, I never could quite settle, supposing I were a moth, whether I would rather be kept out of the candle, or be allowed to fly straight in and get burnt—or again, supposing I were a spider, I’m not sure if I should be quite pleased to have my web torn down, and the fly let loose—but I feel quite certain that, if I were a beetle and had rolled over on my back, I should always be glad to be helped up again.

So, as I was saying, I had gone down upon one knee, and was just reaching out a little stick to turn the Beetle over, when I saw a sight that made me draw back hastily and hold my breath, for fear of making any noise and frightening the little creature a way.

Not that she looked as if she would be easily frightened: she seemed so good and gentle that I’m sure she would never expect that any one could wish to hurt her. She was only a few inches high, and was dressed in green, so that you really would hardly have noticed her among the long grass; and she was so delicate and graceful that she quite seemed to belong to the place, almost as if she were one of the flowers. I may tell you, besides, that she had no wings (I don’t believe in Fairies with wings), and that she had quantities of long brown hair and large earnest brown eyes, and then I shall have done all I can to give you an idea of her.

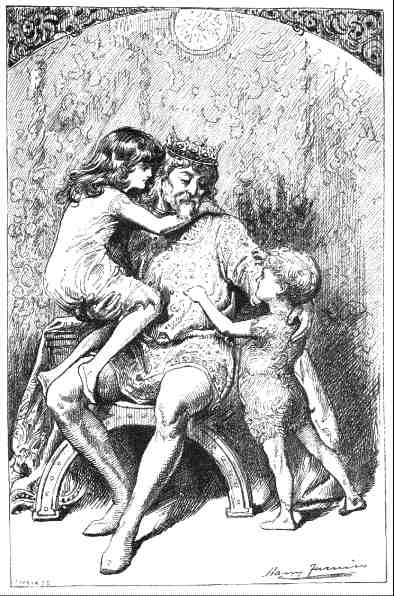

Sylvie (I found out her name afterwards) had knelt down, just as I was doing, to help the Beetle; but it needed more than a little stick for her to get it on its legs again; it was as much as she could do, with both arms, to roll the heavy thing over; and all the while she was talking to it, half scolding and half comforting, as a nurse might do with a child that had fallen down.

“There, there! You needn’t cry so much about it. You’re not killed yet—though if you were, you couldn’t cry, you know, and so it’s a general rule against crying, my dear! And how did you come to tumble over? But I can see well enough how it was—I needn’t ask you that—walking over sand-pits with your chin in the air, as usual. Of course if you go among sand-pits like that, you must expect to tumble. You should look.”

The Beetle murmured something that sounded like “I did look,” and Sylvie went on again.

“But I know you didn’t! You never do! You always walk with your chin up—you’re so dreadfully conceited. Well, let’s see how many legs are broken this time. Why, none of them, I declare! And what’s the good of having six legs, my dear, if you can only kick them all about in the air when you tumble? Legs are meant to walk with, you know. Now don’t begin putting out your wings yet; I’ve more to say. Go to the frog that lives behind that buttercup—give him my compliments—Sylvie’s compliments—can you say compliments’?”

The Beetle tried and, I suppose, succeeded.

“Yes, that’s right. And tell him he’s to give you some of that salve I left with him yesterday. And you’d better get him to rub it in for you. He’s got rather cold hands, but you mustn’t mind that.”

I think the Beetle must have shuddered at this idea, for Sylvie went on in a graver tone. “Now you needn’t pretend to be so particular as all that, as if you were too grand to be rubbed by a frog. The fact is, you ought to be very much obliged to him. Suppose you could get nobody but a toad to do it, how would you like that?”

There was a little pause, and then Sylvie added “Now you may go. Be a good beetle, and don’t keep your chin in the air.” And then began one of those performances of humming, and whizzing, and restless banging about, such as a beetle indulges in when it has decided on flying, but hasn’t quite made up its mind which way to go. At last, in one of its awkward zigzags, it managed to fly right into my face, and, by the time I had recovered from the shock, the little Fairy was gone.

I looked about in all directions for the little creature, but there was no trace of her—and my ‘eerie’ feeling was quite gone off, and the crickets were chirping again merrily—so I knew she was really gone.

And now I’ve got time to tell you the rule about the crickets. They always leave off chirping when a Fairy goes by—because a Fairy’s a kind of queen over them, I suppose—at all events it’s a much grander thing than a cricket —so whenever you’re walking out, and the crickets suddenly leave off chirping, you may be sure that they see a Fairy.

I walked on sadly enough, you may be sure. However, I comforted myself with thinking “It’s been a very wonderful afternoon, so far. I’ll just go quietly on and look about me, and I shouldn’t wonder if I were to come across another Fairy somewhere.”

Peering about in this way, I happened to notice a plant with rounded leaves, and with queer little holes cut in the middle of several of them. “Ah, the leafcutter bee!” I carelessly remarked—you know I am very learned in Natural History (for instance, I can always tell kittens from chickens at one glance)—and I was passing on, when a sudden thought made me stoop down and examine the leaves.

Then a little thrill of delight ran through me —for I noticed that the holes were all arranged so as to form letters; there were three leaves side by side, with “B,” “R,” and “U” marked on them, and after some search I found two more, which contained an “N” and an “O.”

And then, all in a moment, a flash of inner light seemed to illumine a part of my life that had all but faded into oblivion—the strange visions I had experienced during my journey to Elveston: and with a thrill of delight I thought “Those visions are destined to be linked with my waking life!”

By this time the ‘eerie’ feeling had come back again, and I suddenly observed that no crickets were chirping; so I felt quite sure that “Bruno was somewhere very near.

And so indeed he was—so near that I had very nearly walked over him without seeing him; which would have been dreadful, always supposing that Fairies can be walked over my own belief is that they are something of the nature of Will-o’-the-wisps: and there’s no walking over them.

Think of any pretty little boy you know, with rosy cheeks, large dark eyes, and tangled brown hair, and then fancy him made small enough to go comfortably into a coffee-cup, and you’ll have a very fair idea of him.

“What’s your name, little one?” I began, in as soft a voice as I could manage. And, by the way, why is it we always begin by asking little children their names? Is it because we fancy a name will help to make them a little bigger? You never thought of as king a real large man his name, now, did you? But, however that may be, I felt it quite necessary to know his name; so, as he didn’t answer my question, I asked it again a little louder. “What’s your name, my little man?”

“What’s oors?” he said, without looking up.

I told him my name quite gently, for he was much too small to be angry with.

“Duke of Anything?” he asked, just looking at me for a moment, and then going on with his work.

“Not Duke at all,” I said, a little ashamed of having to confess it.

“Oo’re big enough to be two Dukes,” said the little creature. “I suppose oo’re Sir Something, then?”

“No,” I said, feeling more and more ashamed. “I haven’t got any title.”

The Fairy seemed to think that in that case I really wasn’t worth the trouble of talking to, for he quietly went on digging, and tearing the flowers to pieces.

After a few minutes I tried again. “Please tell me what your name is.”

“Bruno,” the little fellow answered, very readily. “Why didn’t oo say ‘please’ before?”

“That’s something like what we used to be taught in the nursery,” I thought to myself, looking back through the long years (about a hundred of them, since you ask the question), to the time when I was a little child. And here an idea came into my head, and I asked him “Aren’t you one of the Fairies that teach children to be good?”

“Well, we have to do that sometimes,” said Bruno, “and a dreadful bother it is.” As he said this, he savagely tore a heartsease in two, and trampled on the pieces.

“What are you doing there, Bruno?” I said.

“Spoiling Sylvie’s garden,” was all the answer Bruno would give at first. But, as he went on tearing up the flowers, he muttered to himself “The nasty cross thing wouldn’t let me go and play this morning,—said I must finish my lessons first—lessons, indeed! I’ll vex her finely, though!”

“Oh, Bruno, you shouldn’t do that!” I cried. “Don’t you know that’s revenge? And revenge is a wicked, cruel, dangerous thing!”

“River-edge?” said Bruno. “What a funny word! I suppose oo call it cruel and dangerous ‘cause, if oo wented too far and tumbleded in, oo’d get drownded.”

“No, not river-edge,” I explained: “revenge” (saying the word very slowly). But I couldn’t help thinking that Bruno’s explanation did very well for either word.

“Oh!” said Bruno, opening his eyes very wide, but without trying to repeat the word.

“Come! Try and pronounce it, Bruno!” I said, cheerfully. “Re-venge, re-venge.”

But Bruno only tossed his little head, and said he couldn’t; that his mouth wasn’t the right shape for words of that kind. And the more I laughed, the more sulky the little fellow got about it.

“Well, never mind, my little man!” I said. “Shall I help you with that job?”

“Yes, please,” Bruno said, quite pacified. “Only I wiss I could think of somefin to vex her more than this. Oo don’t know how hard it is to make her angry!”

“Now listen to me, Bruno, and I’ll teach you quite a splendid kind of revenge!”

“Somefin that’ll vex her finely?” he asked with gleaming eyes.

“Something that will vex her finely. First, we’ll get up all the weeds in her garden. See, there are a good many at this end quite hiding the flowers.”

“But that won’t vex her!” said Bruno.

“After that,” I said, without noticing the remark, “we’ll water this highest bed—up here. You see it’s getting quite dry and dusty.”

Bruno looked at me inquisitively, but he said nothing this time.

“Then after that,” I went on, “the walks want sweeping a bit; and I think you might cut down that tall nettle—it’s so close to the garden that it’s quite in the way—”

“What is oo talking about?” Bruno impatiently interrupted me. “All that won’t vex her a bit!”

“Won’t it?” I said, innocently. “Then, after that, suppose we put in some of these coloured pebbles—just to mark the divisions between the different kinds of flowers, you know. That’ll have a very pretty effect.”

Bruno turned round and had another good stare at me. At last there came an odd little twinkle into his eyes, and he said, with quite a new meaning in his voice, “That’ll do nicely. Let’s put ‘em in rows—all the red together, and all the blue together. "

“That’ll do capitally,” I said; “and then—what kind of flowers does Sylvie like best?”

Bruno had to put his thumb in his mouth and consider a little before he could answer. “Violets,” he said, at last.

“There’s a beautiful bed of violets down by the brook—”

“Oh, let’s fetch ‘em!” cried Bruno, giving a little skip into the air. “Here! Catch hold of my hand, and I’ll help oo along. The grass is rather thick down that way.”

I couldn’t help laughing at his having so entirely forgotten what a big creature he was talking to. “No, not yet, Bruno,” I said: “we must consider what’s the right thing to do first. You see we’ve got quite a business before us.”

“Yes, let’s consider,” said Bruno, putting his thumb into his mouth again, and sitting down upon a dead mouse.

“What do you keep that mouse for?” I said. “You should either bury it, or else throw it into the brook.”

“Why, it’s to measure with!” cried Bruno. “How ever would oo do a garden without one? We make each bed three mouses and a half long, and two mouses wide.”

I stopped him, as he was dragging it off by the tail to show me how it was used, for I was half afraid the ‘eerie’ feeling might go off before we had finished the garden, and in that case I should see no more of him or Sylvie. “I think the best way will be for you to weed the beds, while I sort out these pebbles, ready to mark the walks with.”

“That’s it!” cried Bruno. “And I’ll tell oo about the caterpillars while we work.”

“Ah, let’s hear about the caterpillars,” I said, as I drew the pebbles together into a heap and began dividing them into colours.

And Bruno went on in a low, rapid tone, more as if he were talking to himself. “Yesterday I saw two little caterpillars, when I was sitting by the brook, just where oo go into the wood. They were quite green, and they had yellow eyes, and they didn’t see me. And one of them had got a moth’s wing to carry—a great brown moth’s wing, oo know, all dry, with feathers. So he couldn’t want it to eat, I should think—perhaps he meant to make a cloak for the winter?”

“Perhaps,” I said, for Bruno had twisted up the last word into a sort of question, and was looking at me for an answer.

One word was quite enough for the little fellow, and he went on merrily. “Well, and so he didn’t want the other caterpillar to see the moth’s wing, oo know—so what must he do but try to carry it with all his left legs, and he tried to walk on the other set. Of course he toppled over after that.”

“After what?” I said, catching at the last word, for, to tell the truth, I hadn’t been attending much.

“He toppled over,” Bruno repeated, very gravely, “and if oo ever saw a caterpillar topple over, oo’d know it’s a welly serious thing, and not sit grinning like that—and I sha’n’t tell oo no more!”

“Indeed and indeed, Bruno, I didn’t mean to grin. See, I’m quite grave again now.”

But Bruno only folded his arms, and said “Don’t tell me. I see a little twinkle in one of oor eyes—just like the moon.”

“Why do you think I’m like the moon, Bruno?” I asked.

“Oor face is large and round like the moon,” Bruno answered, looking at me thoughtfully. “It doosn’t shine quite so bright—but it’s more cleaner.”

I couldn’t help smiling at this. “You know I sometimes wash my face, Bruno. The moon never does that.”

“Oh, doosn’t she though!” cried Bruno; and he leant forwards and added in a solemn whisper, “The moon’s face gets dirtier and dirtier every night, till it’s black all across. And then, when it’s dirty all over—so—” (he passed his hand across his own rosy cheeks as he spoke) “then she washes it.”

“Then it’s all clean again, isn’t it?”

“Not all in a moment,” said Bruno. “What a deal of teaching oo wants! She washes it little by little—only she begins at the other edge, oo know.”

By this time he was sitting quietly on the dead mouse with his arms folded, and the weeding wasn’t getting on a bit: so I had to say “Work first, pleasure afterwards: no more talking till that bed’s finished.”