The Warden entered at this moment: and close behind him came the Lord Chancellor, a little flushed and out of breath, and adjusting his wig, which appeared to have been dragged partly off his head.

“But where is my precious child?” my Lady enquired, as the four took their seats at the small side-table devoted to ledgers and bundles and bills.

“He left the room a few minutes ago with the Lord Chancellor,” the Sub-Warden briefly explained.

“Ah!” said my Lady, graciously smiling on that high official. “Your Lordship has a very taking way with children! I doubt if any one could gain the ear of my darling Uggug so quickly as you can!” For an entirely stupid woman, my Lady’s remarks were curiously full of meaning, of which she herself was wholly unconscious.

The Chancellor bowed, but with a very uneasy air. “I think the Warden was about to speak,” he remarked, evidently anxious to change the subject.

But my Lady would not be checked. “He is a clever boy,” she continued with enthusiasm, “but he needs a man like your Lordship to draw him out!”

The Chancellor bit his lip, and was silent. He evidently feared that, stupid as she looked, she understood what she said this time, and was having a joke at his expense. He might have spared himself all anxiety: whatever accidental meaning her words might have, she herself never meant anything at all.

“It is all settled!” the Warden announced, wasting no time over preliminaries. “The Sub-Wardenship is abolished, and my brother is appointed to act as Vice-Warden whenever I am absent. So, as I am going abroad for a while, he will enter on his new duties at once.”

“And there will really be a Vice after all?” my Lady enquired.

“I hope so!” the Warden smilingly replied.

My Lady looked much pleased, and tried to clap her hands: but you might as well have knocked two feather-beds together, for any noise it made. “When my husband is Vice,” she said, “it will be the same as if we had a hundred Vices!”

“Hear, hear!” cried the Sub-Warden.

“You seem to think it very remarkable,” my Lady remarked with some severity, “that your wife should speak the truth!”

“No, not remarkable at all!” her husband anxiously explained. “Nothing is remarkable that you say, sweet one!”

My Lady smiled approval of the sentiment, and went on. “And am I Vice-Wardeness?”

“If you choose to use that title,” said the Warden: “but ‘Your Excellency’ will be the proper style of address. And I trust that both ‘His Excellency’ and ‘Her Excellency’ will observe the Agreement I have drawn up. The provision I am most anxious about is this.” He unrolled a large parchment scroll, and read aloud the words “‘item, that we will be kind to the poor.’ The Chancellor worded it for me,” he added, glancing at that great Functionary. “I suppose, now, that word ‘item’ has some deep legal meaning?”

“Undoubtedly!” replied the Chancellor, as articulately as he could with a pen between his lips. He was nervously rolling and unrolling several other scrolls, and making room among them for the one the Warden had just handed to him. “These are merely the rough copies,” he explained: “and, as soon as I have put in the final corrections—” making a great commotion among the different parchments, “—a semi-colon or two that I have accidentally omitted—” here he darted about, pen in hand, from one part of the scroll to another, spreading sheets of blotting-paper over his corrections, “all will be ready for signing.”

“Should it not be read out, first?” my Lady enquired.

“No need, no need!” the Sub-Warden and the Chancellor exclaimed at the same moment, with feverish eagerness.

“No need at all,” the Warden gently assented. “Your husband and I have gone through it together. It provides that he shall exercise the full authority of Warden, and shall have the disposal of the annual revenue attached to the office, until my return, or, failing that, until Bruno comes of age: and that he shall then hand over, to myself or to Bruno as the case may be, the Wardenship, the unspent revenue, and the contents of the Treasury, which are to be preserved, intact, under his guardianship.”

All this time the Sub-Warden was busy, with the Chancellor’s help, shifting the papers from side to side, and pointing out to the Warden the place whew he was to sign. He then signed it himself, and my Lady and the Chancellor added their names as witnesses.

“Short partings are best,” said the Warden. “All is ready for my journey. My children are waiting below to see me off” He gravely kissed my Lady, shook hands with his brother and the Chancellor, and left the room.

The three waited in silence till the sound of wheels announced that the Warden was out of hearing: then, to my surprise, they broke into peals of uncontrollable laughter.

“What a game, oh, what a game!” cried the Chancellor. And he and the Vice-Warden joined hands, and skipped wildly about the room. My Lady was too dignified to skip, but she laughed like the neighing of a horse, and waved her handkerchief above her head: it was clear to her very limited understanding that something very clever had been done, but what it was she had yet to learn.

“You said I should hear all about it when the Warden had gone,” she remarked, as soon as she could make herself heard.

“And so you shall, Tabby!” her husband graciously replied, as he removed the blotting-paper, and showed the two parchments lying side by side. “This is the one he read but didn’t sign: and this is the one he signed but didn’t read! You see it was all covered up, except the place for signing the names—”

“Yes, yes!” my Lady interrupted eagerly, and began comparing the two Agreements.

“‘Item, that he shall exercise the authority of Warden, in the Warden’s absence.’ Why, that’s been changed into ‘shall be absolute governor for life, with the title of Emperor, if elected to that office by the people.’ What! Are you Emperor, darling?”

“Not yet, dear,” the Vice-Warden replied. “It won’t do to let this paper be seen, just at present. All in good time.”

My Lady nodded, and read on. “‘Item, that we will be kind to the poor.’ Why, that’s omitted altogether!”

“Course it is!” said her husband. “We’re not going to bother about the wretches!”

“Good,” said my Lady, with emphasis, and read on again. “‘Item, that the contents of the Treasury be preserved intact.’ Why, that’s altered into ‘shall be at the absolute disposal of the Vice-Warden’! “Well, Sibby, that was a clever trick! All the Jewels, only think! May I go and put them on directly?”

“Well, not just yet, Lovey,” her husband uneasily replied. “You see the public mind isn’t quite ripe for it yet. We must feel our way. Of course we’ll have the coach-and-four out, at once. And I’ll take the title of Emperor, as soon as we can safely hold an Election. But they’ll hardly stand our using the Jewels, as long as they know the Warden’s alive. We must spread a report of his death. A little Conspiracy—”

“A Conspiracy!” cried the delighted lady, clapping her hands. “Of all things, I do like a Conspiracy! It’s so interesting!”

The Vice-Warden and the Chancellor interchanged a wink or two. “Let her conspire to her heart’s content!” the cunning Chancellor whispered. “It’ll do no harm!”

“And when will the Conspiracy—”

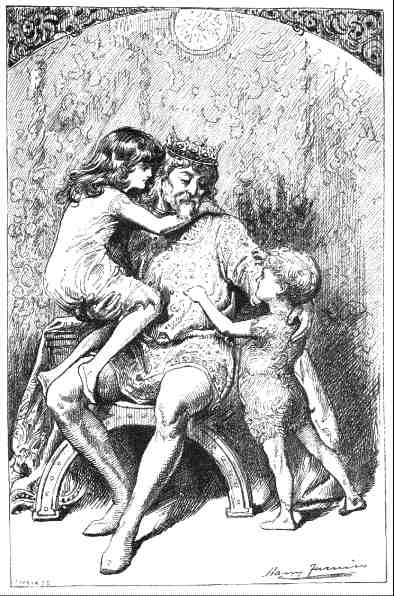

“Hist!’, her husband hastily interrupted her, as the door opened, and Sylvie and Bruno came in, with their arms twined lovingly round each other—Bruno sobbing convulsively, with his face hidden on his sister’s shoulder, and Sylvie more grave and quiet, but with tears streaming down her cheeks.

“Mustn’t cry like that!” the Vice-Warden said sharply, but without any effect on the weeping children. “Cheer ‘em up a bit!” he hinted to my Lady.

“Cake!” my Lady muttered to herself with great decision, crossing the room and opening a cupboard, from which she presently returned with two slices of plum-cake. “Eat, and don’t cry!” were her short and simple orders: and the poor children sat down side by side, but seemed in no mood for eating.

For the second time the door opened—or rather was burst open, this time, as Uggug rushed violently into the room, shouting “that old Beggars come again!”

“He’s not to have any food—” the Vice-warden was beginning, but the Chancellor interrupted him. “It’s all right,” he said, in a low voice: “the servants have their orders.”

“He’s just under here,” said Uggug, who had gone to the window, and was looking down into the court-yard.

“Where, my darling?” said his fond mother, flinging her arms round the neck of the little monster. All of us (except Sylvie and Bruno, who took no notice of what was going on) followed her to the window. The old Beggar looked up at us with hungry eyes. “Only a crust of bread, your Highness!” he pleaded.

He was a fine old man, but looked sadly ill and worn. “A crust of bread is what I crave!” he repeated. “A single crust, and a little water!”

“Here’s some water, drink this!”

Uggug bellowed, emptying a jug of water over his head.

“Well done, my boy!” cried the Vice-Warden.

“That’s the way to settle such folk!”

“Clever boy!”, the Wardeness chimed in. “Hasn’t he good spirits?”

“Take a stick to him!” shouted the Vice-Warden, as the old Beggar shook the water from his ragged cloak, and again gazed meekly upwards.

“Take a red-hot poker to him!” my Lady again chimed in.

Possibly there was no red-hot poker handy: but some sticks were forthcoming in a moment, and threatening faces surrounded the poor old wanderer, who waved them back with quiet dignity. “No need to break my old bones,” he said. “I am going. Not even a crust!”

“Poor, poor old man!” exclaimed a little voice at my side, half choked with sobs. Bruno was at the window, trying to throw out his slice of plum-cake, but Sylvie held him back.

“He shalt have my cake!” Bruno cried, passionately struggling out of Sylvie’s arms.

“Yes, yes, darling!” Sylvie gently pleaded. “But don’t throw it out! He’s gone away, don’t you see? Let’s go after him.” And she led him out of the room, unnoticed by the rest of the party, who were wholly absorbed in watching the old Beggar.

The Conspirators returned to their seats, and continued their conversation in an undertone, so as not to be heard by Uggug, who was still standing at the window.

“By the way, there was something about Bruno succeeding to the Wrardenship,” said my Lady. “How does that stand in the new Agreement?”

The Chancellor chuckled. “Just the same, word for word,” he said, “with one exception, my Lady. Instead of ‘Bruno,’ I’ve taken the liberty to put in—” he dropped his voice to a whisper, “to put in ‘Uggug,’ you know!”

“Uggug, indeed!” I exclaimed, in a burst of indignation I could no longer control. To bring out even that one word seemed a gigantic effort: but, the cry once uttered, all effort ceased at once: a sudden gust swept away the whole scene, and I found myself sitting up, staring at the young lady in the opposite corner of the carriage, who had now thrown back her veil, and was looking at me with an expression of amused surprise.