“It isn’t bed-time!” said a sleepy little voice. “The owls hasn’t gone to bed, and I s’a’n’t go to seep wizout oo sings to me!”

“Oh, Bruno!” cried Sylvie. “Don’t you know the owls have only just got up? But the frogs have gone to bed, ages ago.”

“Well, I aren’t a frog,” said Bruno.

“What shall I sing?” said Sylvie, skilfully avoiding the argument.

“Ask Mister Sir,” Bruno lazily replied, clasping his hands behind his curly head, and lying back on his fern-leaf, till it almost bent over with his weight. “This aren’t a comfable leaf, Sylvie. Find me a comfabler—please!” he added, as an after-thought, in obedience to a warning finger held up by Sylvie. “I doosn’t like being feet-upwards!”

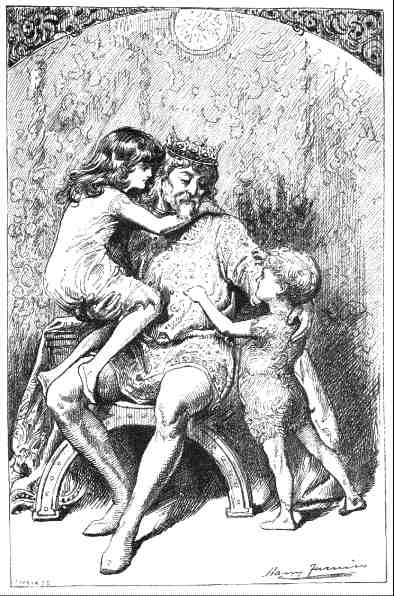

It was a pretty sight to see the motherly way in which the fairy-child gathered up her little brother in her arms, and laid him on a stronger leaf. She gave it just a touch to set it rocking, and it went on vigorously by itself, as if it contained some hidden machinery. It certainly wasn’t the wind, for the evening-breeze had quite died away again, and not a leaf was stirring over our heads.

“Why does that one leaf rock so, without the others?” I asked Sylvie. She only smiled sweetly and shook her head. “I don’t know why,” she said. “It always does, if it’s got a fairy-child on it. It has to, you know.”

“And can people see the leaf rock, who ca’n’t see the Fairy on it?”

“Why, of course!” cried Sylvie. “A leaf’s a leaf, and everybody can see it; but Bruno’s Bruno, and they ca’n’t see him, unless they’re eerie, like you.”

Then I understood how it was that one sometimes sees —going through the woods in a still evening—one fern-leaf rocking steadily on, all by itself. Haven’t you ever seen that? Try if you can see the fairy-sleeper on it, next time; but don’t pick the leaf, whatever you do; let the little one sleep on!

But all this time Bruno was getting sleepier and sleepier. “Sing, sing!” he murmured fretfully, Sylvie looked to me for instructions. “What shall it be?” she said. “Could you sing him the nursery-song you once told me of? I suggested. “The one that had been put through the mind-mangle, you know. ‘The little man that had a little gun,’ I think it was.”

“Why, that are one of the Professor’s songs!” cried Bruno. “I likes the little man; and I likes the way they spinned him—like a teetle-totle-tum.” And he turned a loving look on the gentle old man who was sitting at the other side of his leaf-bed, and who instantly began to sing, accompanying himself on his Outlandish guitar, while the snail, on which he sat, waved its horns in time to the music.

-

- In stature the Manlet was dwarfish—

- No burly big Blunderbore he:

- And he wearily gazed on the crawfish

- His Wifelet had dressed for his tea.

- “Now reach me, sweet Atom, my gunlet,

- And hurl the old shoelet for luck:

- Let me hie to the bank of the runlet,

- And shoot thee a Duck!

-

- She has reached him his minikin gunlet:

- She has hurled the old shoelet for luck:

- She is busily baking a bunlet

- To welcome him home with his Duck.

- On he speeds, never wasting a wordlet

- Though thoughtlets cling, closely as wax

- To the spot where the beautiful birdlet

- So quietly quacks.

-

- Where the Lobsterlet lurks, and the Crablet

- So slowly and sleepily crawls:

- Where the Dolphin’s at home, and the Dablet

- Pays long ceremonious calls:

- Where the Grublet is sought by the Froglet:

- Where the Frog is pursued by the Duck:

- Where the Ducklet is chased by the Doglet—

- So runs the world’s luck!

-

- He has loaded with bullet and powder:

- His footfall is noiseless as air:

- But the Voices grow louder and louder,

- And bellow, and bluster, and blare.

- They bristle before him and after,

- They flutter above and below,

- Shrill shriekings of lubberly laughter,

- Weird wailings of woe!

-

- They echo without him, within him:

- They thrill through his whiskers and beard:

- Like a teetotum seeming to spin him,

- With sneers never hitherto sneered.

- “Avengement,” they cry, “on our Foelet!

- Let the Manikin weep for our wrongs!

- Let us drench him, from toplet to toelet,

- With Nursery-Songs!

-

- “He shall muse upon ‘Hey! Diddle! Diddle!’

- On the Cow that surmounted the Moon:

- He shall rave of the Cat and the Fiddle,

- And the Dish that eloped with the Spoon:

- And his soul shall be sad for the Spider,

- When Miss Muffet was sipping her whey,

- That so tenderly sat down beside her,

- And scared her away!

-

- “The music of Midsummer-madness

- Shall sting him with many a bite,

- Till, in rapture of rollicking sadness,

- He shall groan with a gloomy delight:

- He shall swathe him, like mists of the morning,

- In platitudes luscious and limp,

- Such as deck, with a deathless adorning,

- The Song of the Shrimp!

-

- “When the Ducklet’s dark doom is decided,

- We will trundle him home in a trice:

- And the banquet, so plainly provided,

- Shall round into rose-buds and rice:

- In a blaze of pragmatic invention

- He shall wrestle with Fate, and shall reign:

- But he has not a friend fit to mention,

- So hit him again!”

-

- He has shot it, the delicate darling!

- And the Voices have ceased from their strife:

- Not a whisper of sneering or snarling,

- as he carries it home to his wife:

- Then, cheerily champing the bunlet

- His spouse was so skilful to bake,

- He hies him once more to the runlet,

- To fetch her the Drake!

“He’s sound asleep now,” said Sylvie, carefully tucking in the edge of a violet-leaf, which she had been spreading over him as a sort of blanket: “good night!”

“Good night!” I echoed.

“You may well say ‘good night’!” laughed Lady Muriel, rising and shutting up the piano as she spoke. “When you’ve been nid—nid—nodding all the time I’ve been singing for your benefit! What was it all about, now?” she demanded imperiously.

“Something about a duck?” I hazarded. “Well, a bird of some kind?” I corrected myself, perceiving at once that that guess was wrong, at any rate.

“Something about a bird of some kind!” Lady Muriel repeated, with as much withering scorn as her sweet face was capable of conveying. “And that’s the way he speaks of Shelley’s Sky-Lark, is it? When the Poet particularly says ‘Hail to thee, blithe spirit! Bird thou never wert!’”

She led the way to the smoking-room, where, ignoring all the usages of Society and all the instincts of Chivalry, the three Lords of the Creation reposed at their ease in low rocking-chairs, and permitted the one lady who was present to glide gracefully about among us, supplying our wants in the form of cooling drinks, cigarettes, and lights. Nay, it was only one of the three who had the chivalry to go beyond the common-place “thank you”, and to quote the Poet’s exquisite description of how Geraint, when waited on by Enid, was moved

- “To stoop and kiss the tender little thumb

- That crossed the platter as she laid it down,”

and to suit the action to the word—an audacious liberty for which, I feel bound to report, he was not duly reprimanded.

As no topic of conversation seemed to occur to any one, and as we were, all four, on those delightful terms with one another (the only terms, I think, on which any friendship, that deserves the name of intimacy, can be maintained) which involve no sort of necessity for speaking for mere speaking’s sake, we sat in silence for some minutes.

At length I broke the silence by asking “Is there any fresh news from the harbour about the Fever?”

“None since this morning,” the Earl said, looking very grave. “But that was alarming enough. The Fever is spreading fast: the London doctor has taken fright and left the place, and the only one now available isn’t a regular doctor at all: he is apothecary, and doctor, and dentist, and I don’t know what other trades, all in one. It’s a bad outlook for those poor fishermen—and a worse one for all the women and children.”

“How many are there of them altogether?” Arthur asked.

“There were nearly one hundred, a week ago,” said the Earl: “but there have been twenty or thirty deaths since then.”

“And what religious ministrations are there to be had?”

“There are three brave men down there,” the Earl replied, his voice trembling with emotion, “gallant heroes as ever won the Victoria Cross! I am certain that no one of the three will ever leave the place merely to save his own life. There’s the Curate: his wife is with him: they have no children. Then there’s the Roman Catholic Priest. And there’s the Wesleyan Minister. They go amongst their own flocks mostly; but I’m told that those who are dying like to have any of the three with them. How slight the barriers seem to be that part Christian from Christian when one has to deal with the great facts of Life and the reality of Death!”

“So it must be, and so it should be—” Arthur was beginning, when the front-door bell rang, suddenly and violently.

We heard the front-door hastily opened, and voices outside: then a knock at the door of the smoking-room, and the old house-keeper appeared, looking a little scared.

“Two persons, my Lord, to speak with Dr. Forester.”

Arthur stepped outside at once, and we heard his cheery “Well, my men?” but the answer was less audible, the only words I could distinctly catch being “ten since morning, and two more just—”

“But there is a doctor there?” we heard Arthur say and a deep voice, that we had not heard before, replied “Dead, Sir. Died three hours ago.”

Lady Muriel shuddered, and hid her face in her hands: but at this moment the front-door was quietly closed, and we heard no more.

For a few minutes we sat quite silent: then the Earl left the room, and soon returned to tell us that Arthur had gone away with the two fishermen, leaving word that he would be back in about an hour. And, true enough, at the end of that interval—during which very little was said, none of us seeming to have the heart to talk—the front-door once more creaked on its rusty hinges, and a step was heard in the passage, hardly to be recognized as Arthur’s, so slow and uncertain was it, like a blind man feeling his way.

He came in, and stood before Lady Muriel, resting one hand heavily on the table, and with a strange look in his eyes, as if he were walking in his sleep.

“Muriel—my love—” he paused, and his lips quivered: but after a minute he went on more steadily. “Muriel—my darling—they—want me—down in the harbour.”

“Must you go?” she pleaded, rising and laying her hands on his shoulders, and looking up into his face with great eyes brimming over with tears. “Must you go, Arthur? It may mean—death!”

He met her gaze without flinching. “It does mean death,” he said, in a husky whisper: “but—darling—I am called. And even my life itself—” His voice failed him, and he said no more.

For a minute she stood quite silent, looking upwards in a helpless gaze, as if even prayer were now useless, while her features worked and quivered with the great agony she was enduring. Then a sudden inspiration seemed to come upon her and light up her face with a strange sweet smile. “Your life?” she repeated. “It is not yours to give!”

Arthur had recovered himself by this time, and could reply quite firmly, “That is true,” he said. “It is not mine give. It is yours, now, my—wife that is to be! And you—do you forbid me to go? Will you not spare me, my own beloved one?”

Still clinging to him, she laid her head softly on his breast. She had never done such a thing in my presence before, and I knew how deeply she must be moved. “I will spare you”, she said, calmly and quietly, “to God.”

“And to God’s poor,” he whispered.

“And to God’s poor,” she added. “When must it be, sweet love?”

“To-morrow morning,” he replied. “And I have much to do before then.”

And then he told us how he had spent his hour of absence. He had been to the Vicarage, and had arranged for the wedding to take place at eight the next morning (there was no legal obstacle, as he had, some time before this, obtained a Special Licence) in the little church we knew so well. “My old friend here”, indicating me, “will act as ‘Best Man’, I know: your father will be there to give you away: and—and—you will dispense with bride’s-maids, my darling?”

She nodded: no words came.

“And then I can go with a willing heart—to do God’s work—knowing that we are one—and that we are together in spirit, though not in bodily presence—and are most of all together when we pray! Our prayers will go up together—”

“Yes, yes!” sobbed Lady Muriel. “But you must not stay longer now, my darling! Go home and take some rest. You will need all your strength to-morrow—”

“Well, I will go,” said Arthur. “We will be here in good time to-morrow. Good night, my own own darling!”

I followed his example, and we two left the house together. As we walked back to our lodgings, Arthur sighed deeply once or twice, and seemed about to speak—but no words came, till we had entered the house, and had lit our candles, and were at our bedroom-doors. Then Arthur said “Good night, old fellow! God bless you!”

“God bless you!” I echoed from the very depths of my heart.

We were back again at the Hall by eight in the morning, and found Lady Muriel and the Earl, and the old Vicar, waiting for us. It was a strangely sad and silent party that walked up to the little church and back, and I could not help feeling that it was much more like a funeral than a wedding: to Lady Muriel it was in fact, a funeral rather than a wedding, so heavily did the presentiment weigh upon her (as she told us afterwards) that her newly-won husband was going forth to his death.

Then we had breakfast; and, all too soon, the vehicle was at the door, which was to convey Arthur, first to his lodgings, to pick up the things he was taking with him and then as far towards the death-stricken hamlet as it was considered safe to go. One or two of the fishermen were to meet him on the road, to carry his things the rest of the way.

“And are you quite sure you are taking all that you need?” Lady Muriel asked. “All that I shall need as a doctor, certainly. And my personal needs are few: I shall not even take any of own wardrobe—there is a fisherman’s suit, ready-made, that is waiting for me at my lodgings. I shall only take my watch, and a few books, and—stay—there is one book I should like to add, a pocket-Testament—to use at the bedsides of the sick and dying—”

Take mine!” said Lady Muriel: and she ran upstairs to fetch it. “It has nothing written in it but ‘Muriel’,” she said as she returned with it: “shall I inscribe—” ‘, my own one,” said Arthur, taking it from her. “What could you inscribe better than that? Could any human name mark it more clearly as my own individual property? Are you not mine? Are you not,” (with all the old playfulness of manner) “as Bruno would say, ‘my very mine’?”

He bade a long and loving adieu to the Earl and to me, and left the room, accompanied only by his wife, who was bearing up bravely, and was—outwardly, at least—less overcome than her old father. We waited in the room a minute or two, till the sounds of wheels had told us that Arthur had driven away; and even then we waited still, for the step of Lady Muriel, going upstairs to her room, to die away in the distance. Her step, usually so light and joyous, now sounded slow and weary, like one who plods on under a load of hopeless misery; and I felt almost as hopeless, and almost as wretched as she. “Are we four destined ever to meet again, on this side the grave?” I asked myself, as I walked to my home. And the tolling of a distant bell seemed to answer me, “No! No! No!”