The year—what an eventful year it had been for me,— was drawing to a close, and the brief wintry day hardly gave light enough to recognize the old familiar objects bound up with so many happy memories, as the train glided round the last bend into the station, and the hoarse cry of “Elveston! Elveston!” resounded along the platform.

It was sad to return to the place, and to feel that I should never again see the glad smile of welcome, that had awaited me here so few months ago. “And yet, if I were to find him here,” I muttered, as in solitary state I followed the porter, who was wheeling my luggage on a barrow, “and if he were to ’strike a sudden hand in mine, And ask a thousand things of home,’ I should not—no, ’I should not feel it to be strange’!”

Having given directions to have my luggage taken to my old lodgings, I strolled off alone, to pay a visit, before settling down in my own quarters, to my dear old friends—for such I indeed felt them to be, though it was barely half a year since first we met—the Earl and his widowed daughter.

The shortest way, as I well remembered, was to cross through the churchyard. I pushed open the little wicket-gate and slowly took my way among the solemn memorials of the quiet dead, thinking of the many who had during the past year, disappeared from the place, and had gone to “join the majority”. A very few steps brought me in sight of the object of my search. Lady Muriel, dressed in the deepest mourning, her face hidden by a long crepe veil, was kneeling before a little marble cross, round which she was fastening a wreath of flowers.

The cross stood on a piece of level turf, unbroken by any mound, and I knew that it was simply a memorial cross, for one whose dust reposed elsewhere, even before reading the simple inscription:

In loving Memory of

ARTHUR FORESTER, M.D.

whose mortal remains lie buried by the sea:

whose spirit has returned to God who gave it.“GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS, THAT

A MAN LAY DOWN HIS LIFE FOR HIS FRIENDS.”

She threw back her veil on seeing me approach, and came forwards to meet me, with a quiet smile, and far more self-possessed than I could have expected.

“It is quite like old times, seeing you here again!” she said, in tones of genuine pleasure. “Have you been to see my father?”

“No,” I said: “I was on my way there, and came through here as the shortest way. I hope he is well, and you also?”

“Thanks, we are both quite well. And you? Are you any better yet?”

“Not much better, I fear: but no worse, I am thankful to say.”

“Let us sit here awhile, and have a quiet chat,” she said. The calmness—almost indifference—of her manner quite took me by surprise. I little guessed what a fierce restraint she was putting upon herself.

“One can be so quiet here,” she resumed. “I come here every—every day.”

“It is very peaceful,” I said.

“You got my letter?”

“Yes, but I delayed writing. It is so hard to say—on paper “

“I know. It was kind of you. You were with us when we saw the last of—” She paused a moment, and went on more hurriedly. “I went down to the harbour several times, but no one knows which of those vast graves it is. However, they showed me the house he died in: that was some comfort. I stood in the very room where—where—” She struggled in vain to go on. The flood-gates had given way at last, and the outburst of grief was the most terrible I had ever witnessed. Totally regardless of my presence, she flung herself down on the turf, burying her face in the grass, and with her hands clasped round the little marble cross. “Oh, my darling, my darling!” she sobbed. “And God meant your life to be so beautiful!”

I was startled to hear, thus repeated by Lady Muriel, the very words of the darling child whom I had seen weeping so bitterly over the dead hare. Had some mysterious influence passed, from that sweet fairy-spirit, ere she went back to Fairyland, into the human spirit that loved her so dearly? The idea seemed too wild for belief. And yet, are there not “more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy”?

“God meant it to be beautiful,” I whispered, “and surely it was beautiful? God’s purpose never fails!” I dared say no more, but rose and left her. At the entrance-gate to the Earl’s house I waited, leaning on the gate and watching the sun set, revolving many memories—some happy, some sorrowful—until Lady Muriel joined me.

She was quite calm again now. “Do come in,” she said. “My father will be so pleased to see you!”

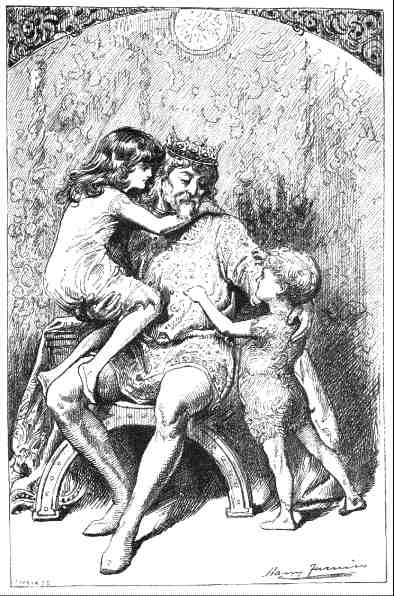

The old man rose from his chair, with a smile, to welcome me; but his self-command was far less than his daughter’s, and the tears coursed down his face as he grasped both my hands in his, and pressed them warmly.

My heart was too full to speak; and we all sat silent for a minute or two. Then Lady Muriel rang the bell for tea. “You do take five o’clock tea, I know!” she said to me, with the sweet playfulness of manner I remembered so well, “even though you ca’n’t work your wicked will on the Law of Gravity, and make the teacups descend into Infinite Space, a little faster than the tea!”

This remark gave the tone to our conversation. By a tacit mutual consent, we avoided, during this our first meeting after her great sorrow, the painful topics that filled our thoughts, and talked like light-hearted children who had never known a care.

“Did you ever ask yourself the question,” Lady Muriel began, à propos of nothing, “what is the chief advantage of being a Man instead of a Dog?”

“No, indeed,” I said: “but I think there are advantages on the Dog’s side of the question as well.

“No doubt,” she replied, with that pretty mock-gravity that became her so well: “but, on Man’s side, the chief advantage seems to me to consist in having pockets! It was borne in upon me—upon us, I should say; for my father and I were returning from a walk—only yesterday. We met a dog carrying home a bone. What it wanted it for, I’ve no idea: certainly there was no meat on it—”

A strange sensation came over me, that I had heard all this, or something exactly like it, before: and I almost expected her next words to be “perhaps he meant to make a cloak for the winter?” However what she really said was “and my father tried to account for it by some wretched joke about pro bono publico. Well, the dog laid down the bone—not in disgust with the pun, which would have shown it to be a dog of taste but simply to rest its jaws, poor thing! I did pity it so! Won’t you join my Charitable Association for supplying dogs with pockets’ How would you like to have to carry your walking-stick in your mouth?”

Ignoring the difficult question as to the raison d’être of a walking-stick, supposing one had no hands, I mentioned a curious instance, I had once witnessed, of reasoning by a dog. A gentleman, with a lady, and child, and a large dog, were down at the end of a pier on which I was walking. To amuse his child, I suppose, the gentleman put down on the ground his umbrella and the lady’s parasol, and then led the way to the other end of the pier, from which he sent the dog back for the deserted articles. I was watching with some curiosity. The dog came racing back to where I stood, but found an unexpected difficulty in picking up the things it had come for. With the umbrella in its mouth, its jaws were so far apart that it could get no firm grip on the parasol. After two or three failures, it paused and considered the matter.

Then it put down the umbrella and began with the parasol. Of course that didn’t open its jaws nearly so wide and it was able to get a good hold of the umbrella, and galloped off in triumph. One couldn’t doubt that it had gone through a real train of logical thought.

I entirely agree with you,” said Lady Muriel. “but don’t orthodox writers condemn that view, as putting Man on the level of the lower animals? Don’t they draw a sharp boundary-line between Reason and Instinct?”

“That certainly was the orthodox view, a generation ago,” said the Earl. “The truth of Religion seemed ready to stand or fall with the assertion that Man was the only reasoning animal. But that is at an end now. Man can still claim certain monopolies—for instance, such a use of language as enables us to utilize the work of many, by division of labour’. But the belief, that we have a monopoly of Reason, has long been swept away. Yet no catastrophe has followed. As some old poet says, ’God is where he was’.”

“Most religious believers would now agree with Bishop Butler,” said I, “and not reject a line of argument, even if it led straight to the conclusion that animals have some kind of soul, which survives their bodily death.”

“I would like to know that to be true!” Lady Muriel exclaimed. “If only for the sake of the poor horses. Sometimes I’ve thought that, if anything could make me cease to believe in a God of perfect justice, it would be the sufferings of horses—without guilt to deserve it, and without any compensation!”

“It is only part of the great Riddle,” said the Earl, “why innocent beings ever suffer. It is a great strain on Faith—but not a breaking strain, I think.”

The sufferings of horses”, I said, “are chiefly caused by Man’s cruelty. So that is merely one of the many instances of Sin causing suffering to others than the Sinner himself. But don’t you find a greater difficulty in sufferings inflicted by animals upon each other? For instance, a cat playing with a mouse. Assuming it to have no moral responsibility, isn’t that a greater mystery than a man over-driving a horse?”

“I think it is,” said Lady Muriel, looking a mute appeal to her father.

“What right have we to make that assumption?” said the Earl. “Many of our religious difficulties are merely deductions from unwarranted assumptions. The wisest answer to most of them, is, I think, ’behold, we know not anything’.”

“You mentioned ‘division of labour’, just now,” I said. “Surely it is carried to a wonderful perfection in a hive of bees?”

“So wonderful—so entirely super-human—” said the Earl, “and so entirely inconsistent with the intelligence they show in other ways—that I feel no doubt at all that it is pure Instinct, and not, as some hold, a very high order of Reason. Look at the utter stupidity of a bee, trying to find its way out of an open window! It doesn’t try, in any reasonable sense of the word: it simply bangs itself about! We should call a puppy imbecile, that behaved so. And yet we are asked to believe that its intellectual level is above Sir Isaac Newton!”

“Then you hold that pure Instinct contains no Reason at all?”

“On the contrary,” said the Earl, “I hold that the work of a bee-hive involves Reason of the highest order. But none of it is done by the Bee. God has reasoned it all out, and has put into the mind of the Bee the conclusions, only, of the reasoning process.”

“But how do their minds come to work together?” I asked.

“What right have we to assume that they have minds?”

“Special pleading, special pleading!” Lady Muriel cried, in a most unfilial tone of triumph. “Why, you yourself said, just now, ‘the mind of the Bee’!”

“But I did not say ’minds’, my child,” the Earl gently replied. “It has occurred to me, as the most probable solution of the ‘Bee’-mystery, that a swarm of Bees have only one mind among them. We often see one mind animating a most complex collection of limbs and organs, when joined together. How do we know that any material connection is necessary? May not mere neighbourhood be enough? If so, a swarm of bees is simply a single animal whose many limbs are not quite close together!”

“It is a bewildering thought,” I said, “and needs a night’s rest to grasp it properly. Reason and Instinct both tell me I ought to go home. So, good-night!”

“I’ll ‘set’ you part of the way,” said Lady Muriel. “I’ve had no walk to-day. It will do me good, and I have more to say to you. Shall we go through the wood? It will be pleasanter than over the common, even though it is getting a little dark.”

We turned aside into the shade of interlacing boughs, which formed an architecture of almost perfect symmetry, grouped into lovely groined arches, or running out, far as the eye could follow, into endless aisles, and chancels, and naves, like some ghostly cathedral, fashioned out of the dream of a moon-struck poet.

“Always, in this wood,” she began after a pause (silence seemed natural in this dim solitude), “I begin thinking of Fairies! May I ask you a question?” she added hesitatingly. “Do you believe in Fairies?”

The momentary impulse was so strong to tell her of my experiences in this very wood, that I had to make a real effort to keep back the words that rushed to my lips. “If you mean, by ‘believe’, ‘believe in their possible existence’, I say ‘Yes’. For their actual existence, of course, one would need evidence.”

“You were saying, the other day”, she went on, “that you would accept anything, on good evidence, that was not à priori impossible. And I think you named Ghosts as an instance of a provable phenomenon. Would Fairies be another instance?”

“Yes, I think so.” And again it was hard to check the wish to say more: but I was not yet sure of a sympathetic listener.

“And have you any theory as to what sort of place they would occupy in Creation? Do tell me what you think about them! Would they, for instance (supposing such beings to exist), would they have any moral responsibility? I mean” (and the light bantering tone suddenly changed to one of deep seriousness) “would they be capable of sin?”

“They can reason—on a lower level, perhaps, than men and women—never rising, I think, above the faculties of a child; and they have a moral sense, most surely. Such a being, without free will, would be an absurdity. So I am driven to the conclusion that they are capable of sin.”

“You believe in them?” she cried delightedly, with a sudden motion as if about to clap her hands. “Now tell me, have you any reason for it?”

And still I strove to keep back the revelation I felt sure was coming. “I believe that there is life everywhere —not material only, not merely what is palpable to our senses—but immaterial and invisible as well; We believe in our own immaterial essence—call it ‘soul, or spirit, or what you will. Why should not other similar essences exist around us, not linked on to a visible and material body? Did not God make this swarm of happy insects, to dance in this sunbeam for one hour of bliss, for no other object, that we can imagine, than to swell the sum of conscious happiness? And where shall we dare to draw the line, and say ‘He has made all these and no more’?”

“Yes, yes”! she assented, watching me with sparkling eyes. “But these are only reasons for not denying. You have more reasons than this, have you not?”

“Well, yes,” I said, feeling I might safely tell all now. “And I could not find a fitter time or place to say it. I have seen them—and in this very wood!”

Lady Muriel asked no more questions. Silently she paced at my side, with head bowed down and hands clasped tightly together. Only, as my tale went on, she drew a little short quick breath now and then, like a child panting with delight. And I told her what I had never yet breathed to any other listener, of my double life, and, more than that (for mine might have been but a noonday-dream), of the double life of those two dear children.

And when I told her of Bruno’s wild gambols, she laughed merrily; and when I spoke of Sylvie’s sweetness and her utter unselfishness and trustful love, she drew a deep breath, like one who hears at last some precious tidings for which the heart has ached for a long while and the happy tears chased one another down her cheeks.

I have often longed to meet an angel,” she whispered so low that I could hardly catch the words. “I’m so glad I’ve seen Sylvie! My heart went out to the child the first moment that I saw her—Listen!” she broke off suddenly. That’s Sylvie singing! I’m sure of it! Don’t you know her voice?”

“I have heard Bruno sing, more than once,” I said: ‘but I never heard Sylvie.”

“I have only heard her once,” said Lady Muriel. “It was that day when you brought us those mysterious flowers. The children had run out into the garden; and I saw Eric coming in that way, and went to the window to meet him: and Sylvie was singing, under the trees, a song I had never heard before. The words were something like ‘I think it is Love, I feel it is Love’. Her voice sounded far away, like a dream, but it was beautiful beyond all words—as sweet as an infant’s first smile, or the first gleam of the white cliffs when one is coming home after weary years—a voice that seemed to fill one’s whole being with peace and heavenly thoughts—Listen!” she cried, breaking off again in her excitement. “That is her voice, and that’s the very song!”

I could distinguish no words, but there was a dreamy sense of music in the air that seemed to grow ever louder and louder, as if coming nearer to us. We stood quite silent, and in another minute the two children appeared, coming straight towards us through an arched opening among the trees. Each had an arm round the other, and the setting sun shed a golden halo round their heads, like what one sees in pictures of saints. They were looking in our direction, but evidently did not see us, and I soon made out that Lady Muriel had for once passed into a condition familiar to me, that we were both of us “eerie”, and that, though we could see the children so plainly, we were quite invisible to them.

The song ceased just as they came into sight: but, to my delight, Bruno instantly said “Let’s sing it all again, Sylvie! It did sound so pretty!” And Sylvie replied “Very well. It’s you to begin, you know.”

So Bruno began, in the sweet childish treble I knew so well:

- “Say, what is the spell, when her fledgelings are cheeping,

- That lures the bird home to her nest?

- Or wakes the tired mother, whose infant is weeping,

- To cuddle and croon it to rest;

- What’s the magic that charms the glad babe in her arms,

- Till it cooes with the voice of the dove?”

And now ensued quite the strangest of all the strange experiences that marked the wonderful year whose history I am writing—the experience of first hearing Sylvie’s voice in song. Her part was a very short one—only a few words—and she sang it timidly, and very low indeed, scarcely audibly, but the sweetness of her voice was simply indescribable; I have never heard any earthly music like it.

- “’Tis a secret, and so let us whisper it low

- And the name of the secret is Love!”

On me the first effect of her voice was a sudden sharp pang that seemed to pierce through one’s very heart. (I had felt such a pang only once before in my life, and it had been from seeing what, at the moment, realized one’s idea of perfect beauty—it was in a London exhibition where, in making my way through a crowd, I suddenly met, face to face, a child of quite unearthly beauty.) Then came a rush of burning tears to the eyes, as though one could weep one’s soul away for pure delight. And lastly there fell on me a sense of awe that was almost terror— some such feeling as Moses must have had when he heard the words “Put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground” The figures of the children became vague and shadowy, like glimmering meteors: while their voices rang together in exquisite harmony as they sang:

- “For I think it is Love

- For I feel it is Love,

- For I’m sure it is nothing but Love!”

By this time I could see them clearly once more. Bruno again sang by himself:

- “Say, whence is the voice that, when anger is burning,

- Bids the whirl of the tempest to cease?

- That stirs the vexed soul with an aching—a yearning

- For the brotherly hand-grip of peace;

- Whence the music that fills all our being—that thrills

- Around us, beneath, and above?”

Sylvie sang more courageously, this time: the words seemed to carry her away, out of herself:

- “’Tis a secret: none knows how it comes, how it goes

- But the name of the secret is Love!”

And clear and strong the chorus rang out:

- “For I think it is Love,

- For I feel it is Love,

- For I’m sure it is nothing but Love!”

Once more we heard Bruno’s delicate little voice alone:

- “Say whose is the skill that paints valley and hill,

- Like a picture so fair to the sight?

- That pecks the green meadow with sunshine and shadow,

- Till the little lambs leap with delight?”

And again uprose that silvery voice, whose angelic sweetness I could hardly bear:

- “’Tis a secret untold to hearts cruel and cold,

- Though ’tis sung, by the angels above,

- In notes that ring clear for the ears that can hear—

- And the name of the secret is Love!”

And then Bruno joined in again with

- “For I think it is Love,

- For I feel it is Love,

- For I’m sure it is nothing but Love!”

“That are pretty!” the little fellow exclaimed, as the children passed us—so closely that we drew back a little to make room for them, and it seemed we had only to reach out a hand to touch them: but this we did not attempt.

“No use to try and stop them!” I said, as they passed away into the shadows. “Why, they could not even see us!”

“No use at all,” Lady Muriel echoed with a sigh. “One would like to meet them again, in living form! But I feel, somehow, that can never be. They have passed out of our lives!” She sighed again; and no more was said, till we came out into the main road, at a point near my lodgings.

“Well; I will leave you here,” she said. “I want to get back before dark: and I have a cottage-friend to visit, first. Good night, dear friend! Let us see you soon—and often!” she added, with an affectionate warmth that went to my very heart. “For those are few we hold as dear!

“Good night!” I answered. “Tennyson said that of a worthier friend than me.”

“Tennyson didn’t know what he was talking about!” she saucily rejoined, with a touch of her old childish gaiety; and we parted.