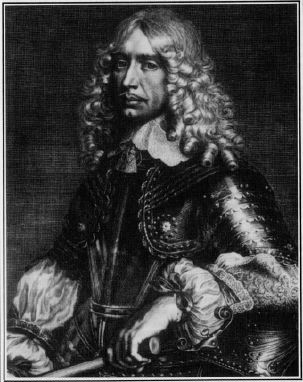

Duc de Beaufort

The man who was set free by Grimaud in Twenty Years After was originally the man most trusted by Queen Anne. When the King died, she “entrusted her children to his safekeeping, afraid that the King’s brother, Gaston, or the Prince de Condé, who was commander-in-chief of the army, might attempt to kidnap the future King.” (Noone, 60) He made the mistake, however, of not only opposing Mazarin, but taking part in the plots against Mazarin’s life. The Queen ordered him arrested and imprisoned at Vincennes, from which he escaped in May 1648 and returned to Paris to help lead the Fronde uprising. Afterwards,

His enemies called him ‘King of the Market’, but at a time when the King of England had just been executed by his people and the King of France was in hiding from his, it was not a title to be scoffed at. (Noone, 60)

Nicolas Fouquet

In following the theories of the man behind the iron mask, John Noone writes in passing:

When Saint-Mars was given command of the state prison in the citadel of Pignerol in January 1665 he had only one prisoner: Nicolas Fouqet. Then aged fifty, the former Superintendent General of Finance had been arrested and imprisoned in September 1661, tried for embezzlement of state funds and conspiracy to rebellion, found guilty and sentenced in December 1664 to imprisonment for life. The troop of musketeers which made the arrest was led by d’Artagnan, more famous from fiction than in fact (Noone, 133)

According to Noone, Fouquet’s major crime was that he was more a king than was the King:

Fouquet was certainly guilty of embezzlement, but in the general corruption of the times that made him no different from anyone else in government or finance. His crime was rather a matter of style; he invented the Louis XIV style before Louis XIV had any style at all. He was everything the young King wished to be and the jealousy and resentment this engendered in the monarch could be appeased by nothing less than the superintendent’s complete destruction…

When he built a house for himself at Vaux-le-Vicomte he created a work of art which set the style in Europe for over a hundred years…

On 17 August 1661, he invited the King and six thousand guests to a party at Vaux… the King was so mortified to find himself the guest of a subject so much more of a king than himself that he very nearly had him arrested on the spot. The guests were overwhelmed by the magnificence of their host, the splendour of the house, the marvel of the garden… There were a hundred tables laid with silver and Venetian lace and the King’s own table was set with massive gold…

Versailles was begun with the spoils of Vaux. The King took its treasures and appropriated its makers… Paintings, sculptures, a thousand orange trees, porcelain, glass and plate, all went to Versailles and with them Le Vau, the architect, Le Nôtre, the gardener, and Le Brun, the decorator… When years later the Sun King finally emerged, tricked out in all his glory, the gross affectation of his posturing was saved from the ridiculous only by the subtle glimmer that still remained of that light which he had stolen from the Superintendent Sun.

Monsieur Laporte

The godfather of Madame Bonacieux fared poorly in the Queen’s demise as well: he went first to the Bastille, and then was exiled to the countryside (Kleinman, 104) for his assistance in carrying the Queen’s letters. He returned to the palace when Anne took power, and was Louis XIV’s tutor for a period. However, his vocal hatred of Richelieu’s successor, Mazarin, resulted in the Queen dismissing him from service.

Interestingly, Laporte may have been related to Cardinal Richelieu: Richelieu’s mother’s side was “the hardworking La Porte-Meilleraye family of robe lineage”. Whether this is the same Laporte family from which Monsieur Laporte came from, I haven’t been able to verify.

Dame Peronne

Given as Anne’s midwife in The Man in the Iron Mask, “we know nothing about Anne’s midwife save her name: Dame Peronne, who, if her name is an indication, probably belonged to a dynasty of midwives long established in Paris.” (Kleinman, 108)

Prince Philippe

In The Man in the Iron Mask, there are two Philippes: the twin brother of the king, and the acknowledged, younger brother of the king, causing no end of confusion to readers toward the end. In real life, of course, there was only the younger brother. He was known as “Monsieur” and his wife, Henrietta Maria, as “Madame”.

Chancellor Séguier

Séguier rates two mentions in “Twenty Years After”. After the Queen, her son the King, Mazarin, and d’Artagnan flee Paris, she sends a message to parliament through Chancellor Séguier. A few chapters later, she instructs Séguier to “open the conferences” with the partisans of the Fronde.

King Charles Stuart (Charles I of England)

In “Twenty Years After”, King Charles’ wife, Queen Henrietta Maria, was in France while Charles fought for his crown in England. Their daughter, also Henrietta, was in France as well, and eventually married Louis XIV’s brother Philippe. Daughter Henrietta was the “Madame” of “Madame and Monsieur” in “The Man in the Iron Mask”. Queen Henrietta Maria was the daughter of the French King Henry IV, Louis XIII’s father. Charles died pretty much exactly as Dumas described, and the Queen’s fate (and her daughter’s) was also as written.

The road to democracy in England was a rocky one. In the beginning, the fight between Parliament and King was as much, or more, a fight between religious extremists on Parliament’s side, who wanted to jail and even hang “papists” who did not adhere to the Anglican or Protestant line, and the King or Queen on the other, who wanted to let “their subjects” live in peace. Parliament made no pretense of fighting for democracy because they didn’t really know what one was. They wanted the same autocratic powers as the king had. This is why, in the history of the events leading up to the American revolution, you often see the Americans pleading to the King to protect them from Parliament.

Charles had declared that anyone arguing that Parliament could overthrow the King’s rule was guilty of treason and should be put to death. He used this declaration to jail and kill members of Parliament. Parliament got tired of this and passed a law that any King who tried to overthrow Parliament’s laws was guilty of treason and should be put to death. Charles refused to acknowledge this law, or that Parliament could pass laws without the King’s approval. This was what Charles refused to acknowledge, and what he meant when he said, in “Remember!”, “To maintain a cause which I believed sacred I have lost the throne”. (Durant VII)

Louise de la Vallière

Louise de la Vallière was originally a maid of honor for Madame, the King’s brother’s wife. According to Kleinman, Vallière was originally used as a ‘blind’, to hide the King’s affair with his own brother’s wife. They were ‘in love’, however, for a time, and she had five children in the affair. The last became Louis de Bourbon, Comte de Vermandois, born on October 2, 1667. After the affair ended, Vallière entered a Carmelite convent. Vermandois and one sister were the only children of the affair to survive infancy. They were raised in the home of Colbert and were acknowledged “and proclaimed legitimate” by their father King Louis XIV. (Noone, 50-15) Vermandois is notable, in real life, as one of the lesser candidates for being the man behind the iron mask.