The Fiftieth Anniversary of Convoy

“Uh, breaker 1-9, this here’s the Rubber Duck. Anybody got a copy on me out there, come on.”

One of the strangest fads to flash through popular culture in the seventies was Citizens Band radio. As a ham radio operator I was only tangentially familiar with it: CB was that thing that people who couldn’t pass a license test used.

But one part of the fad I was very familiar with was C.W. McCall’s part in it, especially his 1975 hit song Convoy. The song was released as part of the Black Bear Road album on September 19, 1975. By January 10 it had reached number 1 on both the Billboard pop singles chart and the Billboard country singles chart.

Convoy was not the first CB-oriented song. Dave Dudley had already done a few, including “Me and Ol’ C.B.” for his own 1975 album Uncommonly Good Country. The trucker-as-cowboy theme was already well-trod territory, and Convoy accelerated the popularity of Citizens Band as a part of that myth. By 1977 there was enough demand for CB songs for an entire album of them, all ears, from, if I’m reading the label correctly, Radio Shack. The title of the album came from C.B. radio slang for an antenna.

C.W. McCall was the outlaw alter ego of Bill Fries and Chip Davis, the latter the founder of the very non-outlaw Mannheim Steamroller. I once, back in the eighties when both country and rap were very different, described C.W. McCall’s best music as a sort of country rap. It is nothing like rap, but it embodies a similar outlaw ethos, a tall-tale storyteller speaking directly to the listener as a real person.

If you’re interested in seventies country music, I’d strongly recommend searching out C.W. McCall’s albums. Besides Black Bear Road, which is a real classic, Wolf Creek Pass and Wilderness are also worth searching out.

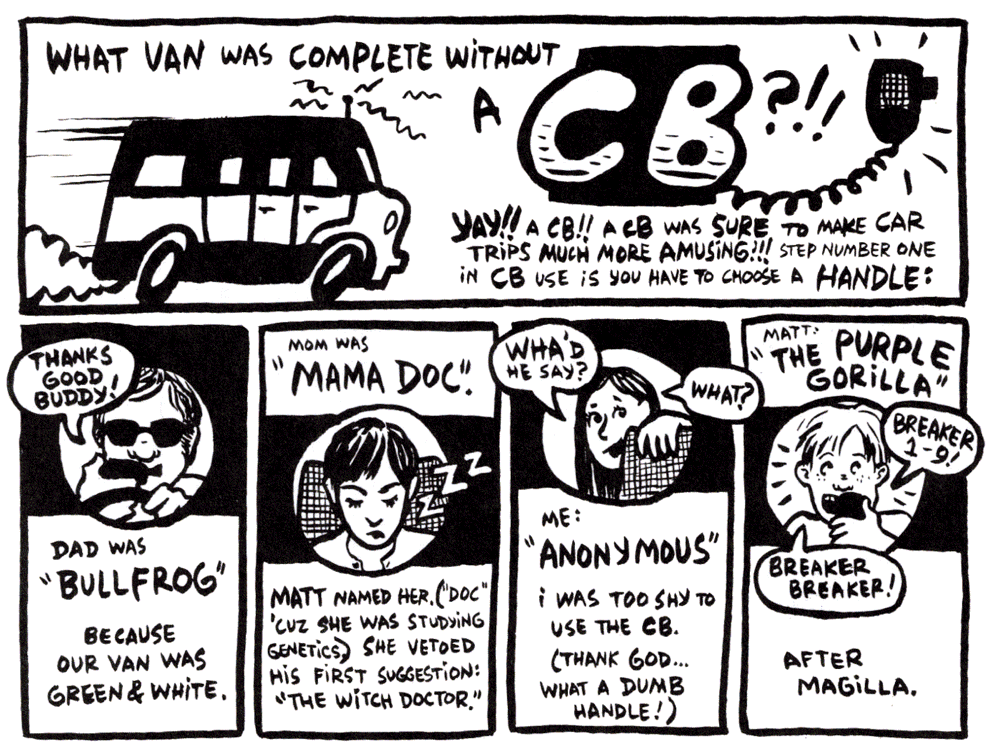

Ellen Forney’s I was Seven in ’75• covers the CB radio craze—and convoys—among other amazing vignettes of the seventies.

Convoy wasn’t McCall’s only hit, but it was by far the most popular, coming in at just the right time to both benefit from and stoke the CB radio fad. It was so popular across so many demographics it was made into a 1978 movie starring Kris Kristofferson, Ali McGraw, and Ernest Borgnine.

McCall made a new version of Convoy for the movie, to more closely reflect the changes in the movie’s story from the original song, and even to reference the sheriff by name.

The movie was hugely popular—and then it disappeared.

I traditionally watch a patriotic movie on July 4, such as 1776: The Musical, Independence Day, or The Patriot. But last year as I was browsing through my movies to find something appropriate for July 4 I noticed I had an Austin City Limits episode on the DVR with Kris Kristofferson. Which led immediately to wondering, what ever happened to the movie Convoy?

Through the wonders of Apple’s universal search, I discovered that Tubi1 had it for free viewing.

I hadn’t remembered Convoy being a 2.35 panoramic movie. I had no idea it was a Sam Peckinpah movie.

The dialogue is bad and the story laughable, which is about how I remember it from when I saw it as a teen. It is, however, just as enjoyable as it was then, and adult me has a better idea of why a movie this poorly written holds up so well. Great direction and cinematography can, if not overcome a bad script, at least compensate for it.

And this is a beautiful movie. Unsurprisingly, Peckinpah treats it as a western. He pulls out all his western shots, especially panoramas, to expand the subculture implied within the McCall song. The characters explicitly reference themselves as cowboys but what they are—as all real cowboys are—is knights. The most westernish, iconically Peckinpah, scenes enclose them completely in their armor, right down to a Seven Samurai-style battle prep outside a small Texas town to free a colleague.

The scenes themselves are perfectly contrasted. Just when I’d start laughing, I’d be jolted into seriousness; just when I started thinking, this is serious, what’s going on here? there was a break to answer that question, to assimilate that seriousness.2 None of that fixes the stupid portrayal of the serious stuff, but on an emotional level a good filmmaking foundation still works even when the superficial aspect of the movie is crap.

It’s disappointing that Convoy didn’t have a better script; even if they’d just written in better dialogue to the same story it would have immeasurably improved.

What makes it a real missed opportunity is that the story revolved around a law that literally everyone broke, from its beginning only four years earlier to its then-unimaginable repeal two decades later: the 55 mile per hour highway speed limit—the “double nickel” in CB slang.

I drove across the country, from Michigan to Los Angeles, in 1988. I don’t remember much about the speed limit’s effect on that trip—I had never driven under anything else—other than that it was followed sporadically at best by other vehicles. I can’t imagine making my living from long hauls and having to drive so slowly.

In 2014 I drove across the country again, from San Diego to Texas to Maryland to New York to Michigan to Los Angeles and back to San Diego. My experience is that people drive much closer to the speed limit now that it ranges mostly from 65 to 85. Except, however, for one place.

As I pulled onto the long east-west highway in New York, traffic was crazy. Everyone was weaving around me at high speed. I had gotten so used to following the speed limit that I was only driving a little above New York’s still-55mph speed limit. I quickly sped up to about 70, still below the prevailing speed, but not dangerously so.

That having a law everyone breaks encourages everyday corruption was something everyone knew and laughed off in 1978. That this everyday corruption also enabled brutal racism everyone also knew. It wasn’t nearly as funny, but what can you do? It’s the law. You can’t fight the law. The law will win.

Peckinpah’s Convoy made this personal, and this part of the story was well-imagined. Rather than the typical mob of bullies against a single victim, Convoy turned this around, and asked, what does it matter? How do you handle a situation where a bully is extorting you in a literal middle of nowhere? Where you outnumber the bully three to one? Where you even have the law on your side? But they have the authority and the gun?

The interaction between Kristofferson’s trucker and Ernest Borgnine’s sheriff was the only relatively well-handled characterization in the movie. There are basically two traditions in movies like this: the hero and the villain are enemies, and they will always be enemies. This is a fight to the death. And then there’s the other tradition where the hero and the villain are in opposition. They know one has to be defeated and may not even survive the fight, but they recognize each other’s heroism.

In Convoy Kristofferson’s trucker wanted to keep their rivalry to the latter kind: if not friendly, at least on a professional level. Borgnine’s sheriff didn’t care about honorable conflict. To him, truckers were marks. He had no respect for truckers, at least at the beginning.

But Borgnine’s Sheriff Wallace did have his own ethical rules. When his colleagues broke those roles he was shocked. Despite that, he remained unwilling to break with his fraternity in favor of his rivals. There’s a lot of that going around in government today.

What happens when bad laws beget violence? What happens when government has no respect for the public? What happens when tribal loyalties overcome principle? These are great questions that deserved a better movie. All Convoy really needed was better dialog. The result would have been a much more impressive, long-lasting movie well suited to Peckinpah’s style. Even with its flaws, Convoy is still worth watching. It’s a wonderful alternate take on the Peckinpah western, and a wonderful taste of a unique period in American popular culture.

Convoy appears to currently be available on Roku.

↑This is as opposed to the undermining of seriousness with humor as modern movies almost inevitably do whenever they accidentally present serious consequences of the movie’s logic.

↑

- C.W. McCall—Convoy

- This is the version of Convoy from the movie, along with scenes from the movie. It may be the German trailer.

- A Chronology of C.W. McCall-related Events at C.W. McCall: An American Legend

- From August 1876 (“Colorado becomes the 38th state”) to 2009 (“C.W. McCall… inducted into the Iowa Rock ’N’ Roll Hame of Fame.”).

- I was Seven in ’75•: Ellen Forney at Amazon.com (comic book)

- A short collection of amazing vignettes about growing up in the seventies.

- Old Home Bread at Texas Archive of the Moving Image

- “Bill Fries created this advertising campaign for Metz Baking Company’s Old Home Bread in 1973… The ads are narrated by singer C. W. McCall (the nom de chanteur for Bill Fries) and feature a truck driver played by Dallas actor Jim Finlayson and a waitress named Mavis Davis, played by Dallas actress Jean McBride Capps.”

- Old Home Bread no. 1 at Old Home Bread

- “This Old Home Bread jingle is narrated by a singer named ‘C. W. McCall’…. This particular advertisement promotes Old Home Stone-Ground Whole Wheat.”

- The Seven Samurai

- Probably the most influential samurai film, starring Toshirô Mifune and directed by Akira Kurosawa. It inspired more than just samurai: “The Magnificent Seven” was “Seven Samurai” remade into one of the most influential westerns.

- San Diego to Louisiana and Back in Three Minutes: Jerry Stratton

- I set the camera on the dashboard and had it take a photo every minute. I drove from San Diego to Dallas, to Georgetown, to Houston, to San Antonio, up through Austin and Round Rock, around the wineries, back up to Dallas, and then back to San Diego. Cross-country driving at its finest.