Recent purchases:

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands—Wednesday, May 22nd, 2024

-

“Last night, I woke up frightened o’ dying… I felt as if everythin’ was lost.”

Why should we care what a comic book writer with aspirations to wizardry has to say about superpowered manipulative bastards? The short answer is, we shouldn’t. But Moore is a very smart and insightful writer. All of the things he has his V and V-adjacent characters do are things that twentieth and twenty-first politicians would like to do. Does it make it okay that unlike everyone else’s eugenics programs throughout the last century and a half, Miracle Man’s is likely to be successful at its goal of improving the human race? Does it matter if Veidt’s murder of millions actually does usher in world peace?

All powerful modern politicians and many powerful modern billionaires claim that turning over individual freedom to the state or to their product will improve lives. Are they right? Does it even matter if they’re right?

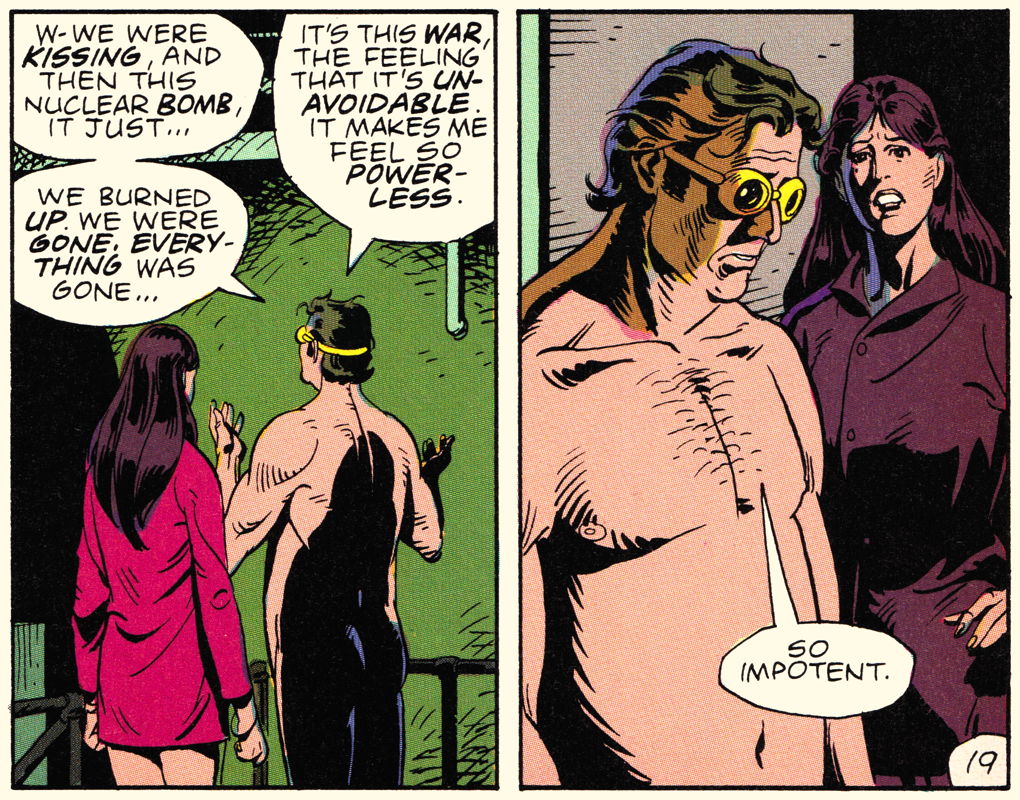

Even if modern technology literally saves us, as it does Cyborg in Twilight, is it right to give so much of our lives over to it?

In Moore’s worlds, your revolutions are only as perfect as your successors. Moore’s Miracleman ends with the complete dehumanization of humanity. Consistent with Moore’s elevation of Hitler as the epitome of the twentieth century, it is one of Gargunza’s South American Nazis who first informs Miracleman that he is humanity’s replacement. The Nazi accepts his own death at Miracleman’s hands, because Miracleman’s impending takeover of the world is what he and the other Nazis have worked their lives for.1

The Qys, the co-rulers of the universe, agree with Gargunza’s Nazis. It is only the perfected miracle-beings who are “not of animal status” in the “intelligent space” of the universe.

Miraclewoman, Avril, fully accepts the Qys’s explanation. Where Michael Moran still retains respect for humanity as humanity, Avril sees humans as herd animals to be shepherded at best and culled to perfection at worst.2

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You—Wednesday, May 8th, 2024

-

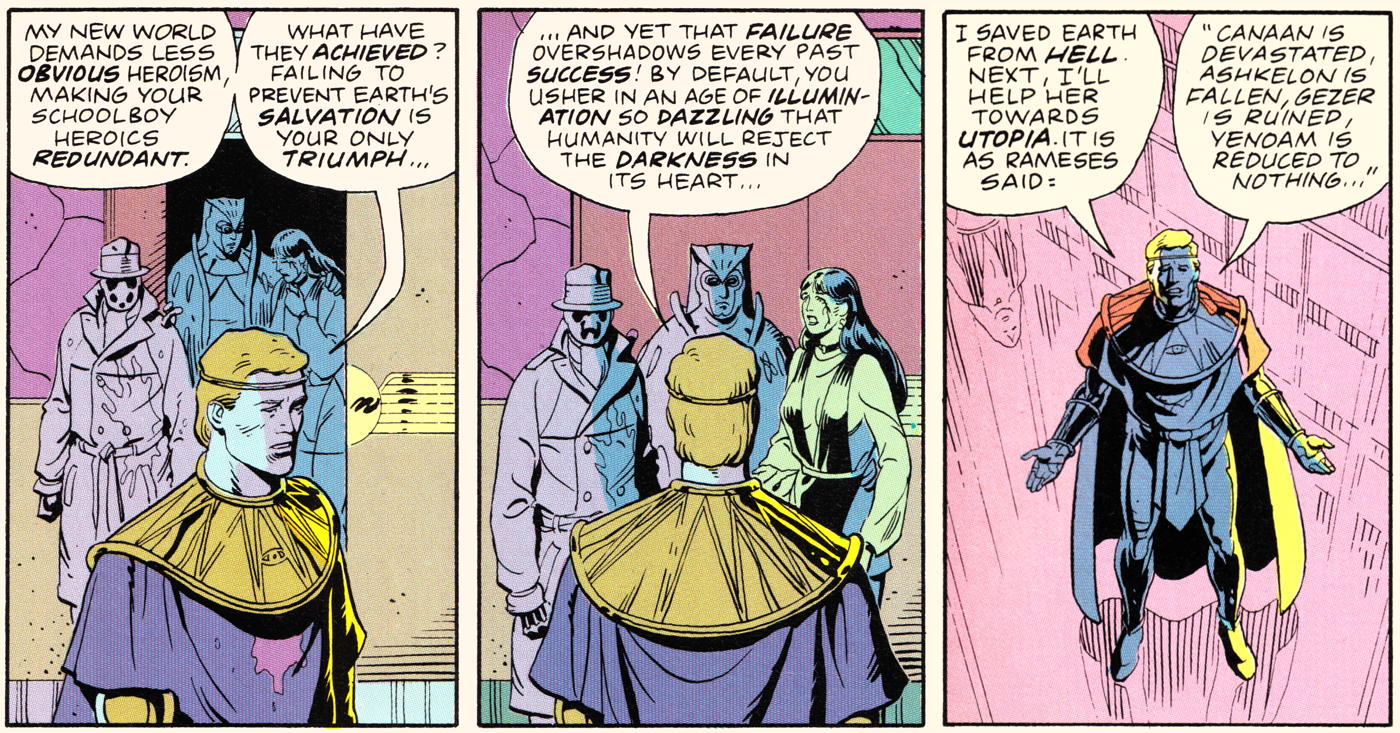

Veidt may believe mankind will reject the “darkness in its heart” and that his destruction of “half of New York” is a forgettable step to his new utopia…

While From Hell and Promethea are V-adjacent, Miracleman isn’t a V tale at all. Miracleman isn’t devious. He doesn’t scheme to supplant humanity; rather, the responsibility is thrust upon him, and he is equal to the task. Miracleman and From Hell are two extreme ends of the graph of perfection. Miracleman is perfect; William Withey Gull is seriously damaged.

Where a stroke left Gull unable to reason and prone to illusions of ascendancy, Michael Moran has successfully ascended, in an origin similar to V’s. Like V, Miracleman escaped and destroyed the medical experimentation camp that created him.1 Unlike V, however, Miracleman really is perfect.2 His tyranny is as perfect a tyranny as man or god could hope to devise. It’s rule by the strong, but the strong provide for the weak, far more than Norsefire in V for Vendetta did. It’s a return to barbarism—to rule by force and whim rather than democracy and law—but it’s a barbarism of plentiful food, plentiful energy, plentiful freedom, and good health.

They have defeated space, and are on the verge of defeating time. And yet:

In all the history of Earth, there’s never been a heaven; never been a house of gods, that was not built on human bones.3

We could easily see Evey or Veidt cradling the dismembered corpse of humanity, crying “I have saved you” as Gull does to Marie Kelly at the end of From Hell4 or as Miracleman does, wordlessly, to young Johnny Bates after crushing the boy’s head.

“I have saved you. Do you understand that? I have made you safe from time.”

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way—Wednesday, April 24th, 2024

-

Promethea directly invokes a connection with Prometheus and stealing fire from the gods. While the Five Swell Guys muck about ineffectually with technology.

If there’s one commonality between Moore’s variant worlds, it is a moral foundation weakened to nonexistence. And if there’s any commonality as to why, it is because technological progress has enervated us. If his appendix to From Hell can be trusted, Moore’s vision of technological progress is a terrifying one. From Hell was set in a squalid pre-technological Eden more alive than the modern world it preceded.

Scientific advances that moved away from the human—such as using dogs to solve crimes—were ridiculed. Gull’s vision of the future showed him a technological Olympus that had reduced mankind to emotional amputees.

In V for Vendetta, as in Orwell’s 1984•, technology exists only for the government to stifle the masses. Promethea gives us a near-future where our marvelous utopia is even more heavenly—and even more enervating and stifling—than what Gull foresaw in From Hell. The Internet exists but has little effect on people’s lives except as a barely mobile telephone/post office. Promethea’s only nods to modernity are the meme-like Weeping Gorilla billboards, a corporate top-down messaging system more like Wells’s Babble Machines in The Sleeper Awakes than modern viral memes. In the world of Promethea Sophie doesn’t even consider using the Internet for research. She goes to the library to find out where Promethea came from.

Superheroes in Promethea are Science Heroes. The main science heroes are the very impotent Five Swell Guys. They have no idea how to classify Promethea, because they can only see her as “some kind of science heroine”.1 They are blind to the mysticism inherent in her.

Promethea highlights both the best and worst of Moore. It’s a sprawling epic filled with emotive personal moments, interspersed with interminable lectures about the nature of illusion and reality, and why a world that most people find perfectly acceptable requires revolution.

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve—Wednesday, April 10th, 2024

-

“The only freedom left to my people is the freedom to get sick. Should I allow them that freedom?”

Is V in V for Vendetta good or evil? Do his ends justify his means? Are his ends even desirable? What Norsefire did to bring peace to England and to bring food to the people was horrific. But what V does to Evey is also horrific, on a personal level, and what V does to the people of England is horrific on a mass level. V, Veidt, and Constantine have a vision, but their methods are as much Jack the Ripper as William Withey Gull’s was in the pursuit of his own vision, and may well share nearly as much of Gull’s madness.

We have little sense of how much of what V says is true, and how much he made up to justify his torture of Evey and England. His motto is By the power of truth, I, while living, have conquered the universe. V, however, uses everything but the truth in his relationship with Evey, creating a semi-imaginary prison and fake death sentence to indoctrinate her into his own version of anarchy.

Evey even acknowledges the technique: she can’t know if the toilet paper memoirs she read when confined are real. But by then she’s internalized V’s worldview enough that it doesn’t matter. Moore leaves no ambiguity here for the reader: she has been brainwashed, using standard brainwashing techniques.

The Norsefire of V for Vendetta succeeded because people were dying of starvation and failing infrastructure. Under Norsefire the people of England didn’t have the plenty available to the typical eighties comic book reader, but neither were they dying of starvation. By the end of the book, what has V given the people of England? Starvation and a broken infrastructure. And we don’t even know if England is free from tyranny!

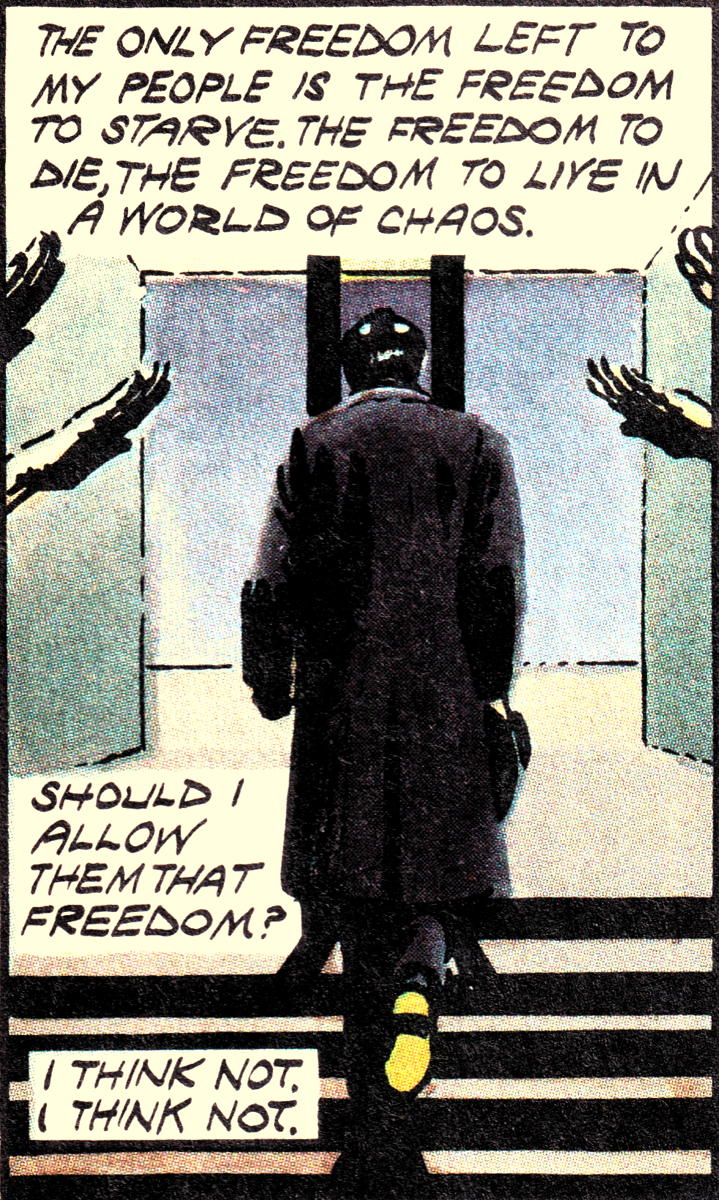

The only freedom left to my people is the freedom to starve. The freedom to die, the freedom to live in a world of chaos. Should I allow them that freedom? I think not.—Adam Susan

As presented in V for Vendetta, this could only be a totalitarian thought. But think of what’s happened over the last four years. Should we have allowed people the freedom to catch COVID? Or should we have let them live in the chaos of freedom of movement, freedom of association, and the choice of how, and whether, to protect themselves against sickness?

If asked in the context of the COVID restrictions of 2020 and the vaccine requirements later, a lot of people today agree with Adam Susan’s conclusion. “I think not.”

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man—Wednesday, March 20th, 2024

-

Twilight is difficult to discuss on the same terms as V or Watchmen because it was never written. All we have is Moore’s proposal to DC Comics. We know from Moore’s recounting of the evolutions of both V for Vendetta and Watchmen that his stories change significantly between the idea and the finished product. The proposal is less a story than an attempt to talk a language DC will understand: how much money DC will make if they accept.

It is very clear, however, that Twilight features a manipulative bastard in John Constantine. Constantine is willing to shed any amount of blood to ensure his vision of a better future for humanity. Constantine even chooses to define what it means to be human. He ruthlessly engineers brutal killings of those who he decides are not human, from the metalman Gold to many of the various alien races in the universe.

In a sense, Twilight is what happens after the last page of V for Vendetta, Watchmen, or Miracleman: one decidedly not superior normal human’s attempt to overthrow objectively superior overlords.

By Promethea, Moore may have finally begun to tire of his manipulative Vs, or he may have wanted to capstone these stories with magic as a redemptive power for humanity. Promethea’s closest manipulative analog, Jack Faust, isn’t even a main character. Most of his manipulations of Sophie and Promethea happen off screen, and it’s debatable how much of an effect Faust had on this incarnation of Promethea or on the success of her Promethean task. But Promethea’s new era of human freedom, like that of V for Vendetta, Watchmen, and Twilight, still only comes after a lot of carnage and death.

Between you and me, I’m terrified.1

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire—Wednesday, March 6th, 2024

-

V walking from the Larkhill Resettlement Camp after setting it on fire.

In V for Vendetta, our protagonist is V, who is single-handedly and violently using his superpowers to overthrow the established right-wing totalitarian government. In Watchmen, our protagonists are superheroes working to maintain an established right-wing democratic government against the single-handed violent reforms of an enlightened mad scientist.

V is a creature of man. In a way, he’s a Frankenstein’s monster, created by a committee of scientists experimenting on individuals for the betterment of society.1 Veidt, on the other hand, is a creature of God—or fate—who was born with his abilities but believes that he’s self-made. Both Veidt and V are intensely smart. In a sense, both are even forged in a crucible of fire. V started a fire to escape the concentration camp where he was held for experimentation. Veidt’s fire was the Comedian burning a map of the United States.2

This was a critical moment in Watchmen: Veidt had, earlier, been bullied and beaten by the Comedian; knowing what we know about the Comedian, it was probably very brutal. When the Comedian burned the map and told the assembled heroes that “It don’t matter squat because inside thirty years the nukes are gonna be flyin’ like maybugs…”, Veidt could have chosen to ignore it, as the rest of the heroes did. He could have chosen to side with humanity, trusting that humanity’s innate wisdom would eventually overcome this future, as it has—so far—in the real world.

Instead, Veidt chose to side with the bully. He internalized the Comedian’s view of the world and set about to fix the world, regardless of the cost in human lives and suffering. In both the Comedian’s view and Veidt’s view, humanity needed protection, and they most needed protection “from themselves”. The Comedian felt that other men needed to be protected from their baser instincts. Veidt, however, felt that humanity needed to be rescued from its lack of foresight.

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior—Wednesday, February 21st, 2024

-

V for Vendetta, Watchmen, Twilight of the Superheroes, and Promethea: There’s a little Jack the Ripper in all of Alan Moore’s best work. He appears to be obsessed with the idea of individuals ushering in a new era of human flourishing by means of secrecy, manipulation, and bloodshed. A new world requires a blood sacrifice, and Moore’s promethean protagonists are willing to provide one.

Whether it works or not.

Moore is not alone among British comic book writers in using superheroes as a means to examine forced transformations of humanity. Grant Morrison’s Zenith and The Invisibles both showed us a war between two forces seeking to overturn humanity; his Doom Patrol featured a weird team seeking to maintain normality in the face of unimaginable change. His Animal Man sought to overturn the very reader of the comic, using possibly the most normal superhero in DC’s pantheon.

But Alan Moore takes the fantastic world of superheroes and crafts direct allegories with the real world more in the lines of a Shakespeare than Morrison’s Hieronymus Bosch.

Even his most psychedelic, Morrison-like comic, Promethea, still features a believable protagonist who craves normality. His most famous comic, Watchmen, is about a handful of individual heroes without the moral strength to oppose the villain’s manipulation. It’s a reverse of his inaugural V for Vendetta which is less about individualism than about one individual strongman. V and Veidt are arguably, like Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion, the same person from different worlds. Yet, while Watchmen’s Veidt is ostensibly the comic book’s villain and V for Vendetta’s V is ostensibly the comic book’s hero, in both cases that status is ambiguous.

V’s enemy is a government put in power/allowed to remain in power by the people, who are too lazy, or too concerned with personal comfort, to topple their totalitarians. Veidt’s enemy is the people, who are too lazy or too concerned with personal entertainment to vote for enlightened rulers.

- My Year in Books: 2023—Wednesday, January 17th, 2024

-

This was a relatively slow year for books. According to Goodreads, I read an even 100, but quite a few of them were cookbooks. I’ll be writing about them later in 2023 in Food. Fictionwise, I started the year with Jack Vance’s Eight Fantasms and Magics. You could hardly do better. Vance is a master of fantasy, and a pretty good hand with science fiction as well. Especially when his science fiction looks like fantasy.

The green light floods the planet, and I prepare for the green day.

I ended the year with Lee Gold’s marvelous fantasy Valhalla: Into the Darkness. Gold is the proprietor of the Alarums & Excursions roleplaying zine (of which I’m a part) and shows the true role-player’s dedication to accurate mythology. While the dead role-player who was the protagonist of the first book remains here, this book’s protagonist is an Internet-obsessed squirrel who lives on the world tree.

I sang as I ran, and I never got tired. I was inspired, rhymes blazing like fire. I can’t even begin to tell you what it was like. When I ran across a patch of ash honey, and the bees swarmed up and stung me, I cried out in joy, because I knew just how they felt.

If you enjoy weird fantasy with a fairy-tale bent that’s deeply rooted in real mythology, you will enjoy Gold’s series.

I read three sailing books toward the end of the year, although only two really count. I finally got around to reading Patrick O’Brian’s Master and Commander; while reading that in paperback, I also started up a new ebook, David Weber’s On Basilisk Station, the first of the Honor Harrington series. I had no idea when I started it that it was clearly either inspired by Master and Commander or by the same books that inspired Master and Commander.