The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

“The only freedom left to my people is the freedom to get sick. Should I allow them that freedom?”

Is V in V for Vendetta good or evil? Do his ends justify his means? Are his ends even desirable? What Norsefire did to bring peace to England and to bring food to the people was horrific. But what V does to Evey is also horrific, on a personal level, and what V does to the people of England is horrific on a mass level. V, Veidt, and Constantine have a vision, but their methods are as much Jack the Ripper as William Withey Gull’s was in the pursuit of his own vision, and may well share nearly as much of Gull’s madness.

We have little sense of how much of what V says is true, and how much he made up to justify his torture of Evey and England. His motto is By the power of truth, I, while living, have conquered the universe. V, however, uses everything but the truth in his relationship with Evey, creating a semi-imaginary prison and fake death sentence to indoctrinate her into his own version of anarchy.

Evey even acknowledges the technique: she can’t know if the toilet paper memoirs she read when confined are real. But by then she’s internalized V’s worldview enough that it doesn’t matter. Moore leaves no ambiguity here for the reader: she has been brainwashed, using standard brainwashing techniques.

The Norsefire of V for Vendetta succeeded because people were dying of starvation and failing infrastructure. Under Norsefire the people of England didn’t have the plenty available to the typical eighties comic book reader, but neither were they dying of starvation. By the end of the book, what has V given the people of England? Starvation and a broken infrastructure. And we don’t even know if England is free from tyranny!

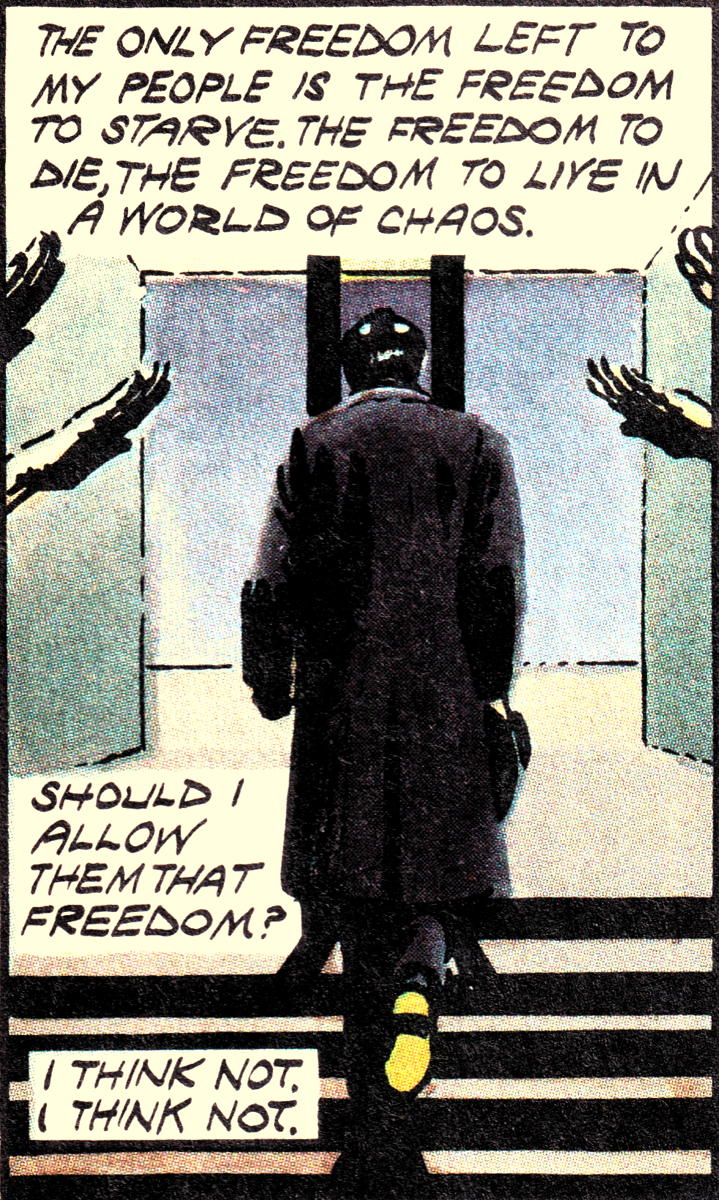

The only freedom left to my people is the freedom to starve. The freedom to die, the freedom to live in a world of chaos. Should I allow them that freedom? I think not.—Adam Susan

As presented in V for Vendetta, this could only be a totalitarian thought. But think of what’s happened over the last four years. Should we have allowed people the freedom to catch COVID? Or should we have let them live in the chaos of freedom of movement, freedom of association, and the choice of how, and whether, to protect themselves against sickness?

If asked in the context of the COVID restrictions of 2020 and the vaccine requirements later, a lot of people today agree with Adam Susan’s conclusion. “I think not.”

Unlike Veidt in Watchmen, who can be treated as a simple villain, whether or not V’s motives are good isn’t actually addressed. It isn’t merely left up to us to answer, it’s left up to us to realize it’s even a question. V is portrayed as a sort of cowboy hero; Moore manages to get both great western endings: V dies with his boots on and rides into the sunset at the end, the last of his kind.

In Westerns, the hero is an anarchic figure made obsolete by his own actions implementing law and order. You can see this best in movies like Who Shot Liberty Valance. V, however, isn’t trying to implement law and order but anarchy. If we can trust him, it’s an anarchy in which people take responsibility for their own government. But once V dies, the reality appears to be that he’s created a terrorist monarchy with Evey at the head.

Like every other Bright Idea in the history of mankind, the devil is in the implementation. Anarchy enforced by a secretive, masked killer? The England of V is far more likely to end as a Jonestown or with a new and more tyrannical Norsefire than as anything good.

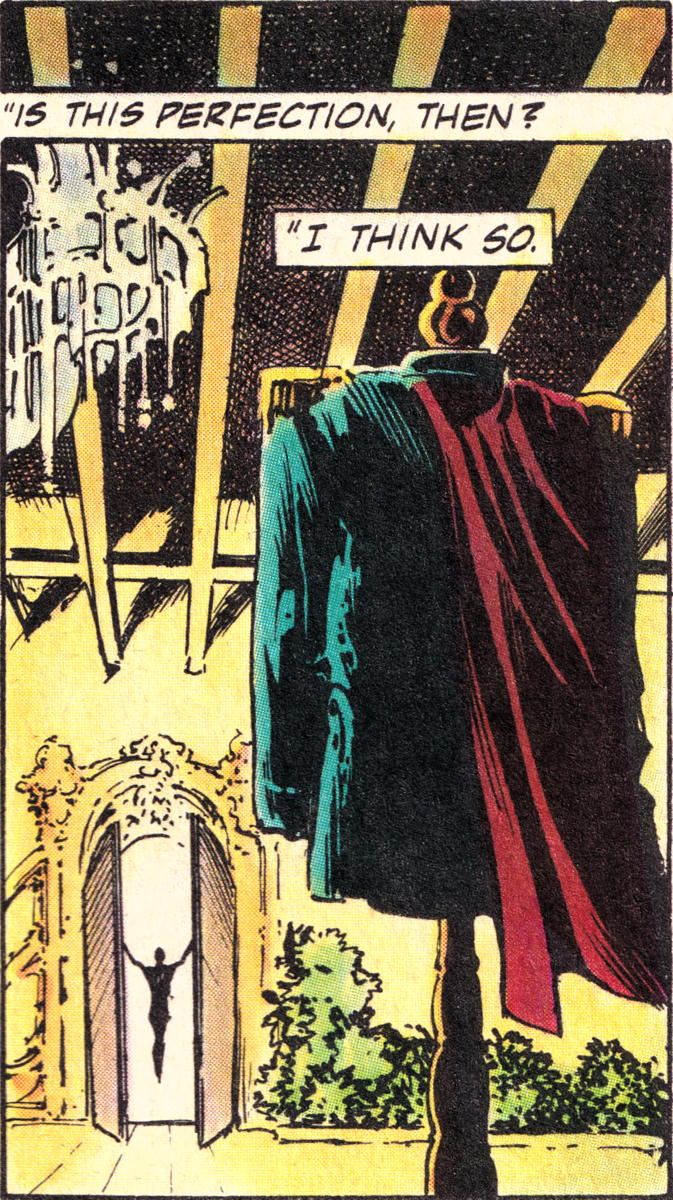

If Adam Susan is a villain, how about Miracleman?

Norsefire’s connection to the great computer FATE has been severed, but Moore made a point of V having a parallel entry into the system. It’s very likely that FATE still exists in post-Norsefire England, now under the control of a single person instead of a sometimes vicious, sometimes bumbling bureaucracy. At the end of the books that person, Evey, has appointed a single successor for reasons not immediately obvious to the reader.

It looks like she’s about to subject him to the same brainwashing techniques that V inflicted on her.

Superficially, Moore in V for Vendetta is asking whether starvation with a side of freedom is better than mostly getting by under a committee-style dictatorship.1 But on a deeper level, he may well be making a point about trusting any political promises. Especially if what they’re really getting under Evey is starvation plus a hereditary dictatorship.

It’s a very difficult theme, and leads to an ending filled with a horror that is difficult to convey—it’s to Moore’s credit that he can convey it, and well. The movie writers, for example, couldn’t handle that horror. Like the generations of filmmakers who turned Lolita from a twelve-year old into a teenage vixen, justifying Humbert Humbert, they changed V for Vendetta from Moore’s vision of burning, bloody anarchy into a sort of outsider nerd gains popular acceptance.

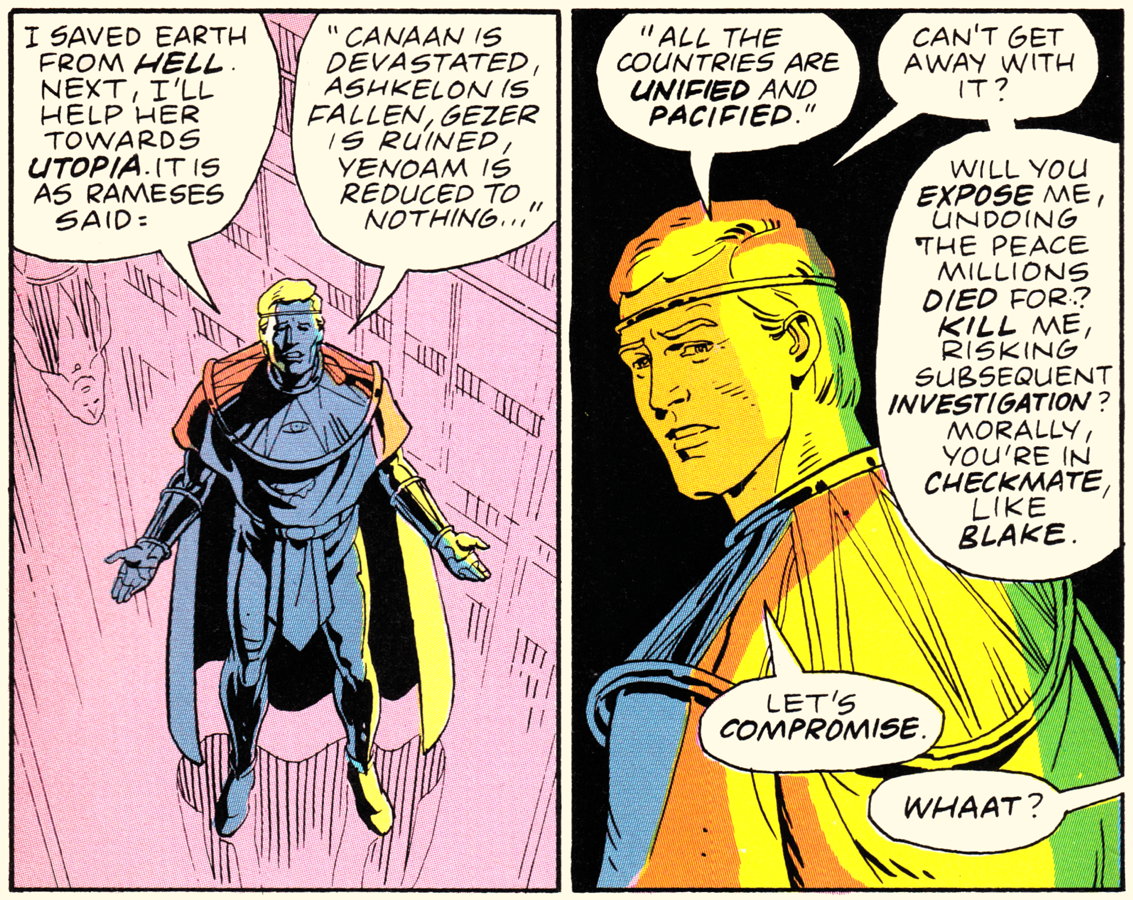

Watchmen is similarly ambiguous in turning not only on whether Veidt’s actions were justified but on whether they were even effective. But while ambiguous, the ending of Watchmen is not as ambiguous as the ending of V for Vendetta. Superficially, Watchmen’s ambiguity hinges on a single point: is Veidt’s plot about to be revealed? Will people believe Rorschach’s ramblings? V for Vendetta’s ambiguity turns on human nature: whether Evey can withstand the lure of power, and who the people of England will turn to in their suffering.

In Twilight, the superheroes themselves are leaders of a pre-modern feudalism, each House the Lewis-style caretakers of the world2. Constantine plays the heroes against each other in order to overthrow the established order and remove superheroes from Earth. Their most likely replacement is a human dictatorship. Moore does not highlight this ambiguity at the end of his Twilight proposal. He glosses over it by promising a utopian democracy:

Constantine explains to them that under the guidance of the Batman, the Shadow and all the rest, American society, free of government or a super-dictatorship, will start to organize itself along different lines, so that it can deal with the future without fear or anxiety. The days of the big powers are over, and henceforth America will be built up from much smaller and more flexible units, both socially and economically.

Veidt is not only more arrogant than Adam Susan or Miracleman—he never questions himself at all—he’s also a lot more pretentious.

It sounds a lot like V’s utopian anarchy. But the idea of “the elite council of the Shadow [and] the Batman” overseeing a new age of flexible democracy is problematic, to say the least. Moore doesn’t specifically describe their organizations, but one point of Twilight was that it leveraged characters we already knew. The Shadow works via infiltration, surveillance, and mental manipulation, as well as a network of spies and thugs. The Batman, especially Frank Miller’s elder Batman from the comic Moore praised in his proposal, relies on an extensive surveillance system and an informal community of gangs that idolize and practically worship him.

Constantine manipulates them all up to the end, with Batman and the Shadow as his SS and SD. If Moore intended this, then the conflict between Constantine’s two enforcement arms will likely be just as bloody once they finally take power.

Moore’s Twilight proposal, however, leaves us with little apparent ambiguity—Constantine is doing good. Like Watchmen, much of the ambiguity comes from whether Constantine’s changes will last. In Watchmen, Veidt’s grand scheme may yet be destroyed posthumously by Rorschach. In Twilight, which relies on time travel, it’s the framing sequence that makes us wonder if the plot will succeed: will the deliberately unpredictable Constantine follow the advice laid out by his future self?

But regardless even of Twilight’s framing ambiguity, Moore would also have added ambiguity to the apparent clarity of its utopia. According to his notes in the trade paperback, V for Vendetta began with similar clarity and grew far more ambiguous through its collaborative writing process. Twilight’s apparent clarity is very unlikely to have lasted through its own writing process: there’s far too much that could go wrong after Constantine’s proposed solution. Can Constantine trust Batman and the Shadow to remain benign ushers of a new order? Should Constantine really have trusted Qward to live up to their agreement and leave Earth alone? Each seems extraordinarily naive for someone like Constantine, but without a final script we don’t know what form those agreements took.

Even without those questions, the battles Constantine caused in Twilight were bloody and destructive. Life on Earth after Constantine, as in England after V, will initially be one of brutish misery, living in the ruins wrought by the book’s supposed hero.

“There’s a lot of hurting a boy goes through if he wants to be a man,” writes Elliot S! Maggin in Superman: Miracle Monday. And there’s a lot of carnage a civilization must suffer to achieve any of Moore’s human utopias.

Especially if civilization itself is dehumanizing.

In response to FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior: V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

Norsefire is only superficially portrayed as a sort of fascism. But there’s no sense that Adam Susan is a charismatic leader in the mold of a Hitler or Mussolini.

↑Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It may be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience. — C. S. Lewis (The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment•)

↑

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way

- Is all power destined to be abused regardless of good intentions? Is technology necessarily dehumanizing? What happens when literally everyone has that technology at all times?

- Satire isn’t comedy

- Satire isn’t comedy. It can be, and often is, but that isn’t what makes it satire.

- Superman: Miracle Monday

- “On that day, according to the book, resort owners on the glaciers of Uranus raise ski-lift tickets for the influx of tourists. Teamsters driving slow-moving cargo transports to Earth from mining operations in the asteroid belt get drunk and silly like sailors crossing the Equator for the first time… There are laughter, reflection, public celebration with barbecues and holographic light shows all over the solar system, merriments of all sorts.”

More Twilight of the Superheroes

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- Time brings progress and it brings suffering. Can humanity be saved from the latter without losing the former? How much can we turn over to machines or governments before we are no longer human or free?

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

More V for Vendetta

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- Moore’s stories aren’t just about overthrowing an oppressive regime. They’re about a superior being overthrowing an oppressive regime because normal humans won’t—they’re doing the job Britons, Americans, and the Worldly Wise won’t do. How much are they about the decline of mankind in favor of something else?

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- V is a creature of man, born of fire and perverted science. He is the savior of man, giving his life to usher in a new world of freedom and individual liberty. Including the liberty to die.

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

- A savior, for people who don’t want to be saved

- The Matrix sequels and V for Vendetta had the same problem: how do you make a movie about a savior? It’s not something Hollywood really believes in.

- V for Vendetta: A Love Story

- The Wachowski brothers took a great book but failed to overcome typical Hollywood cliches, making V for Vendetta little more than a love story for terrorists.

More Watchmen

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- V is a creature of man, born of fire and perverted science. He is the savior of man, giving his life to usher in a new world of freedom and individual liberty. Including the liberty to die.

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?