The Battle of the Kegs

The Battle of the Kegs, as depicted in John Gilmary Shea’s 1872 A Child’s History of the United States.

You may know Francis Hopkinson as one of the less-prominent signers of the Declaration of Independence. But he was much more than a Founder. He was also a poet. I’ve included his wonderful “For a Muse of Fire” in The Padgett Sunday Supper Club Sestercentennial Cookery, which will be the next post in this series. And— he wasn’t just a poet: he was also a satirical poet. This Sunday, January 5, marks the 248th anniversary of the battle that provided him his finest hour as a writer. If there’s a second thing that Hopkinson is remembered for, it is his darkly humorous account of The Battle of the Kegs in rhyme.

- Battle of Bennington

- Upside Down Yorktown

- Cherry Valley Massacre

- Battle of the Kegs ⬅︎

- Sestercentennial Cookery

- The New Colossus

Accounts differ in minor points, but sometime around January 5, 1778, David Bushnell—who had previously made the first combat submarine—released gunpowder-filled kegs onto the Delaware River near Bordentown, New Jersey. His hope was that the kegs would explode on contact with British ships patrolling the harbor.

Most sources say that the plan was performed with the knowledge and approval of General Washington. Presumably, then, there was more to the plan than “gunpowder-filled kegs randomly floating down the river”. The kegs are often described as “contact mines”. The few accounts that describe how the mines were to be ignited describe the fuse as a flintlock fuse.

While there are a lot of places where you can find diagrams of Bushnell’s “Turtle” submarine, I haven’t seen any explicit explanation or diagram of how the flintlock fuse was supposed to work in a very wet environment. The best I can get is that “when the keg bumped into something, it was designed to explode”, which is really just a restatement of what a contact mine is, not the mechanism by which it works.

It could have been one of the stupidest, most wasteful plans ever hatched by a revolutionist. It didn’t do much to the British: January is pretty cold on the Delaware river, and the British had moved their ships to avoid ice floes and had “rigged a perimeter of logs” to further protect them from floating ice. This had the effect of also protecting them from floating kegs. Further, the ice also blocked the kegs from moving as expected. The only damage the kegs caused was to kill either “two… unfortunate boys” or “a curious Philadelphia bargeman”.

But after the explosion alerted them to the danger, on either the fifth or the sixth of January the British began firing on the kegs, turning the affair into one of the funniest events of a revolution not particularly marked with humor. Small kegs on a large waterway are not the most obvious things on a cold and probably misty morning in an ice-filled river, which meant that the British were most likely not just shooting at kegs but at anything that moved on the river, from debris that already existed to debris that their shots created. “In short, not a wandering chip, stick, or drift log, but felt the vigour of the British arms.”

I like to imagine explosions, smoke everywhere, and lots of noise. A real Independence celebration!

Here’s how it was reported in the February 11, 1778, Pennsylvania Ledger:

The city has lately been entertained with a most astonishing instance of the activity, bravery, and military skill of the royal navy of Great Britain. The affair is somewhat particular, and deserves your notice. Some time last week two boys observed a keg of a singular construction, floating in the river opposite to the city, they got into a small boat, and attempting to take up the keg, it burst with a great explosion, and blew up the unfortunate boys. On Monday last several kegs of a like construction made their appearance—An alarm was immediately spread through the city—Various reports prevailed; filling the city and the royal troops with consternation. Some reported that these kegs were filled with armed rebels; who were to issue forth in the dead of night, as the Grecians did of old from their wooden horse at the siege of Troy, and take the city by surprise; asserting that they had seen the points of their bayonets through the bung-holes of the kegs. Others said they were charged with the most inveterate combustibles, to be kindled by secret machinery, and setting the whole Delaware in flames, were to consume all the shipping in the harbour; whilst others asserted that they were constructed by art magic, would of themselves ascend the wharfs in the night time, and roll all flaming thro’ the streets of the city, destroying every thing in their way.—Be this as it may—Certain it is that the shipping in the harbour, and all the wharfs in the city were fully manned—The battle began, and it was surprizing to behold the incessant blaze that was kept up against the enemy, the kegs. Both officers and men exhibited the most unparralled skill and bravery on the occasion; whilst the citizens stood gazing as solemn witnesses of their prowess. From the Roebuck and other ships of war, whole broadsides were poured into the Delaware. In short, not a wandering chip, stick, or drift log, but felt the vigour of the British arms. The action began about sun-rise, and would have been compleated with great success by noon, had not an old market women [sic] coming down the river with provisions, unfortunately let a small keg of butter fall over-board, which (as it was then ebb) floated down to the scene of action. At sight of this unexpected reinforcement of the enemy, the battle was renewed with fresh fury—the firing was incessant till the evening closed the affair. The kegs were either totally demolished or obliged to fly, as none of them have shewn their heads since. It is said his Excellency Lord Howe has dispatched a swift sailing packet with an account of this victory to the court of London. In a word, Monday the1 5th of January 1778, must ever be distinguished in history for the memorable BATTLE OF THE KEGS.

The Ledger attributed their article to “a Letter from Philadelphia, Jan. 9, 1778.”2 The only italicized word in the letter was “heads” toward the end: “as none of them have shewn their heads since.” It’s a pun of sorts: the wooden boards of a keg were held together by hoops at the ends where the boards are curved inward; these hoops were the “head hoops”. The head hoops surround the actual head of the barrel, the flat discs on either end. I think. I am not a cooper, and am definitely not an eighteenth century cooper.

I considered adjusting this account to add paragraphs, but this doesn’t appear to be an artifact of the way printing worked back then. The lack of paragraphs seems to have been deliberate: other articles in the paper are divided into perfectly normal modern paragraphs.

I can’t find any record of when Hopkinson wrote his satirical account of the event, but it was reprinted in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser on Wednesday, March 4, 1778 so presumably before that. They attribute it, if I’m reading it correctly, to the Pennsylvania Packet, but don’t give a date.

British Valour Displayed: Or, The Battle of the Kegs

- Gallants attend, and hear a friend

- Trill forth harmonious ditty;

- Strange things I’ll tell, which late befel

- In Philadelphia city.

- ’Twas early day, as Poets say,

- Just when the sun was rising;

- A soldier stood on a log of wood

- And saw a sight surprising.

- As in a maze he stood to gaze,

- The truth can’t be deny’d, Sir;

- He spied a score of kegs, or more,

- Come floating down the tide, Sir.

- A sailor too, in jerkin blue,

- This strange appearance viewing,

- First damn’d his eyes in great surprise,

- Then said—“some mischief’s brewing:”

- “These kegs now hold the rebels bold

- “Peck’d up like pickl’d herring,

- “And they’re come down t’attack the town

- “In this new way of ferrying.”

- The solder flew, the sailor too,

- And fear’d almost to death, Sir,

- Wore out their shoes to spread the news,

- And ran ’till out of breath, Sir.

- Now up and down throughout the town

- Most frantic scenes were acted;

- And some ran here and others there,

- Like men almost distracted.

- Some fire cry’d, which some deny’d,

- But said the earth had quaked;

- And girls and boys, with hideous noise,

- Ran thro’ the streets half naked.

- Sir William he, snug as a flea,

- Lay all this time a snoring;

- Nor dreamt of harm, as he lay warm

- In bed with Mrs. Loring.

- Now in a fright he starts upright,

- Awak’d by such a clatter;

- First rubs his eyes, then boldly cries,

- “For God’s sake, what’s the matter?”

- At his bed side he then espy’d

- Sir Erskine at command, Sir;

- Upon one foot he had one boot

- And t’other in his hand, Sir.

- “Arise, arise,” Sir Erskine cries,

- “The rebels—more’s the pity!

- “Without a boat, are all afloat

- “And rang’d before the city.

- “The motley crew, in vessels new,

- “With Satan for their guide, Sir,

- “Pack’d up in bags, and wooden kegs,

- “Come driving down the tide, Sir.

- “Therefore prepare for bloody war,

- “These kegs must all be routed,

- “Or surely we despis’d shall be,

- “And British valour doubted.”

- The royal band now ready stand,

- All rang’d in dread array, Sir,

- On every slip, in every ship,

- For to begin the fray, Sir.

- The cannons roar from shore to shore,

- The small arms make a rattle;

- Since wars began I’m sure no man

- E’er saw so strange a battle.

- The rebel dales—the rebel vales,

- With rebel trees surrounded;

- The distant woods, the hills and flood,

- With rebel echoes sounded.

- The fish below swam to and fro,

- Attack’d from ev’ry quarter;

- Why sure, thought they, the De’il’s to pay

- ’Mong folks above the water.

- The kegs, ’tis said, tho’ strongly made

- Of rebel staves and hoops, Sir,

- Could not oppose their pow’rful foes,

- The conqu’ring British troops, Sir.

- From morn to night, these men of might

- Display’d amazing courage;

- And when the sun was fairly down,

- Retir’d to sup their porridge.

- One hundred men, with each a pen

- Or more, upon my word, Sir,

- It is most true, would be too few

- Their valour to record, Sir.

- Such feats did they perform that day

- Against these wicked kegs, Sir,

- That years to come, if they get home,

- They’ll make their boasts and brags, Sir.

As a fan of the musical 1776•, the first verse very obviously fits the melody to Franklin’s introduction to the song The Egg. The Egg stresses and rhymes the same words as and even shares a full line with The Battle of the Kegs. Naturally fitting “In Philadelphia City” to the start of The Egg is how I noticed the similarity—making me wonder if that was deliberate on 1776• writer Sherman Edwards’s• part.

| The Egg | Battle of the Kegs |

|---|---|

|

|

However, using the melody from Franklin’s introduction would get very sing-song very quickly. Musical introductions are not designed for repetition.

A variation of the lyrics appeared in a broadside attributed to the New Jersey Gazette by Wikimedia Commons but they also dated it to a very unlikely “6 January 1778”. While I can find no evidence of this broadside being from the New Jersey Gazette other than that unsourced assertion, I will call it the New Jersey Gazette version for the rest of the post, just to keep things simple.

Most of the differences are moderately interesting variations in things like spelling, punctuation, abbreviations, capitalization, and italicization. There are different choices on how to force the poem into the correct meter as well.

A theologically interesting change in capitalization is that the Poulson version capitalizes “Satan” and “Devil” while the New Jersey Gazette version does not.

The New Jersey Gazette version completely changes half of one of the verses to a much stronger statement:

| Poulson | New Jersey Gazette |

|---|---|

|

|

The New Jersey Gazette version further removes an entire verse:

- The rebel dales—the rebel vales,

- With rebel trees surrounded;

- The distant woods, the hills and flood,

- With rebel echoes sounded.

I wouldn’t read too much into the removal of a verse. Rather than for editorial reasons I suspect it was removed to make the poem fit nicely on a single illustrated page. This also leads me to suspect that the New Jersey Gazette broadside came after the version printed among other content in newspapers. The Library of Congress has a very similar broadside (JPEG Image, 480.8 KB) that, lacking the top graphic and so having more space does include the missing lyric.

More interesting is the replacement of “One hundred men” with “An hundred men” or vice versa. Nowadays I’d say that this means the writer (or typesetter) of the first version of the poem pronounces the “h” in “hundred” and the writer or typesetter of the second does not. But I don’t know if that habit—“a” before consonants and “an” before vowels—was common at the time this was written.

Hopkinson’s poem isn’t just satire. Hidden within a poem about blowing up kegs on the river thinking they were filled with soldiers is also a harsh personal accusation:

- Sir William he, snug as a flea,

- Lay all this time a snoring;

- Nor dreamt of harm, as he lay warm

- In bed with Mrs. Loring.

Both Sir William and Mrs. Loring were real people, which is probably why some printings, such as the New Jersey Gazette version, made the editorial decision to anonymize her name. Or semi-anonymize it. While the New Jersey Gazette version removed every character of her name except the first and last, printing it as “Mrs. L———g”, the version from the Library of Congress merely removed the vowels. That version printed it as “Mrs. L*r*ng”, which is barely a fig leaf of an anonymization given that we already know it has to rhyme with “snoring”.

“Sir William” would have been General William Howe. Joshua Loring, Jr., was Howe’s Commissary General of American prisoners-of-war in New York during this period. “Mrs. Loring” was Elizabeth (Lloyd) Loring, married to Joshua. The accusation appears to be a historical fact. While both Lorings were loyalists that seems to take loyalism a bit far.

The battle, or at least the poem, appears to have remained in the public consciousness for a long time. It was memorable enough to inspire a temperance version in 1854. That version describes a nightmare, possibly of a brewer, possibly after binging on his own product, in which the dreamer descends into hell in a dream.

- “The kegs! the kegs! I’ve drunk the dregs

- Of every horrid brewing!

- ’Twill be too bad if I grow mad,

- ’Twill be the trade’s undoing.”

- …

- “There mountains high the kegs stood dry,

- As Alps on Alps arising!

- And little imps, old Pluto’s pimps,

- There asking ‘Are they pisin??’

- …

- “Then Satan came ’mid smoke and flame,

- And cried, ‘Here’s trouble real!

- It is these kegs, O Mister Megs,

- That make all hell’s ideal?’

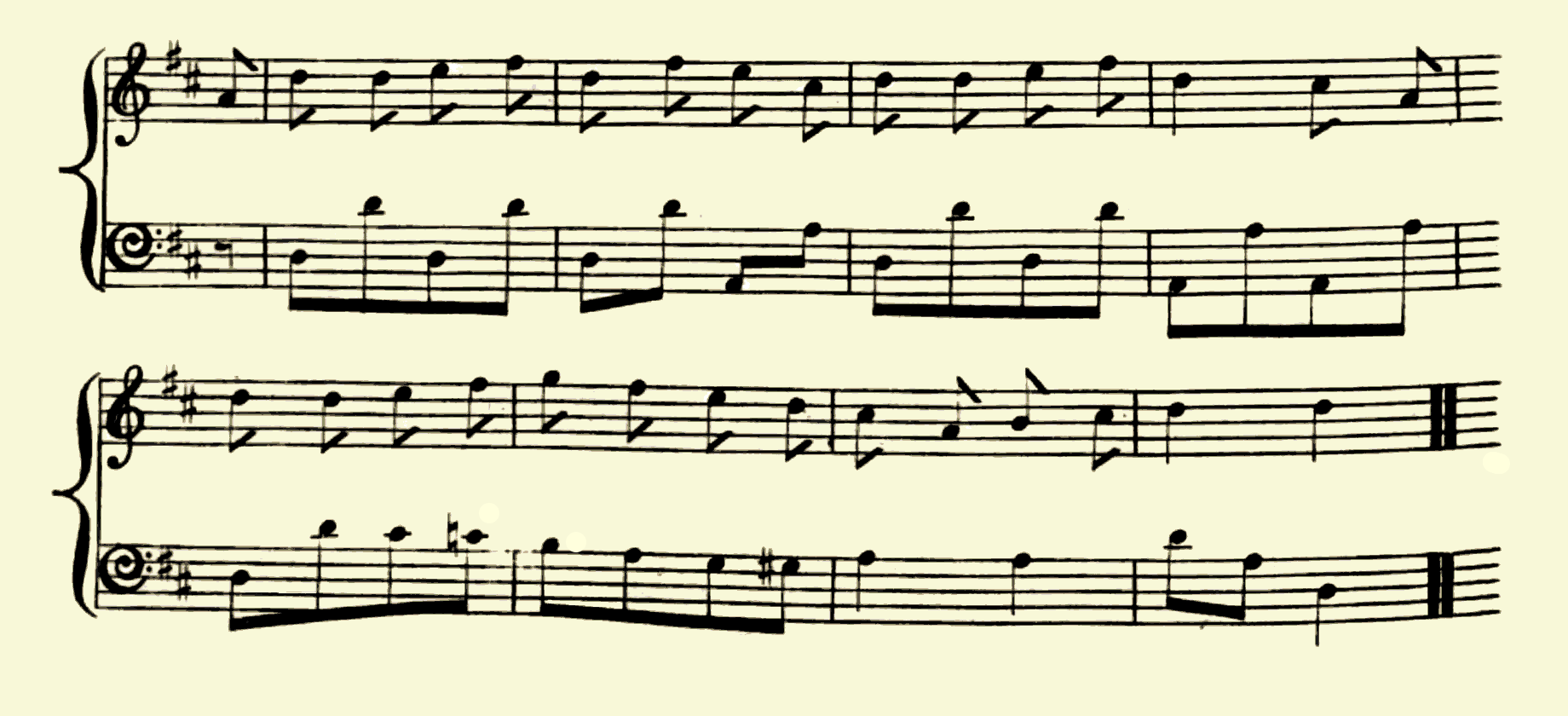

Eric Sterner of Emerging Revolutionary War Era writes that Hopkinson’s poem can be sung to the tune of Yankee Doodle. The last line in each verse occasionally makes it a minorly difficult match but it otherwise works well. You’ll need to ignore the chorus since the poem doesn’t have one—or add one yourself, or just use Yankee Doodle as the chorus, which appears to have been a common expedient.

I first ran across the poem, as a song, in Oscar Brand’s Songs of ’76. Brand leaves out several of the verses (it’s admittedly a long set of lyrics for modern ears) including the verses about General Howe’s affair with the wife of one of his underlings.

Among Brand’s other minor changes, he combines “As in a maze” to “As in amaze”—he was collecting these songs for modern musicians to play to modern listeners, after all. If you look in the various variations, even at the time some printers chose to combine “a fright” to “affright”.

Like Sterner, Brand recommends Yankee Doodle as the melody, and may even be including the “Yankee Doodle, keep it up…” chorus. This song is a good example of how the same tune often gets reused. Brand doesn’t print the melody to Yankee Doodle under “The Battle of the Kegs”. He refers back to “Arnold Is As Brave a Man” for the music. He explicitly does use Yankee Doodle’s chorus with “Arnold Is As Brave a Man”.

In his entry for “Arnold Is As Brave a Man” Brand quotes a contemporary source as dating its lyrics to “soon after the late siege” of Quebec, which would have put it soon after December 30, 1775. According to the quotes Brand supplies, Arnold was specifically printed as “to the Tune ‘Yankee Doodle’”.

I’ve found no such contemporary linkage of Battle of the Kegs to Yankee Doodle or to any other melody, but that doesn’t mean much. Without a specific recommendation it would have been sung to whatever melody the singer preferred, and Yankee Doodle would likely have been a common choice. It’s very possible that the meter was so obviously Yankee Doodle at the time that it would have needed no recommendation.

Yankee Doodle remains even today such a commonly-known melody that I’m not going to make one of my trademark arrangement + slideshow videos. For one, the slideshow would probably have all of one slide. If you want a period arrangement—or close to period—I recommend this 1830 variation (PDF File, 659.5 KB).

It’s a nice arrangement, and a simple one if you leave out the intro and the outro.

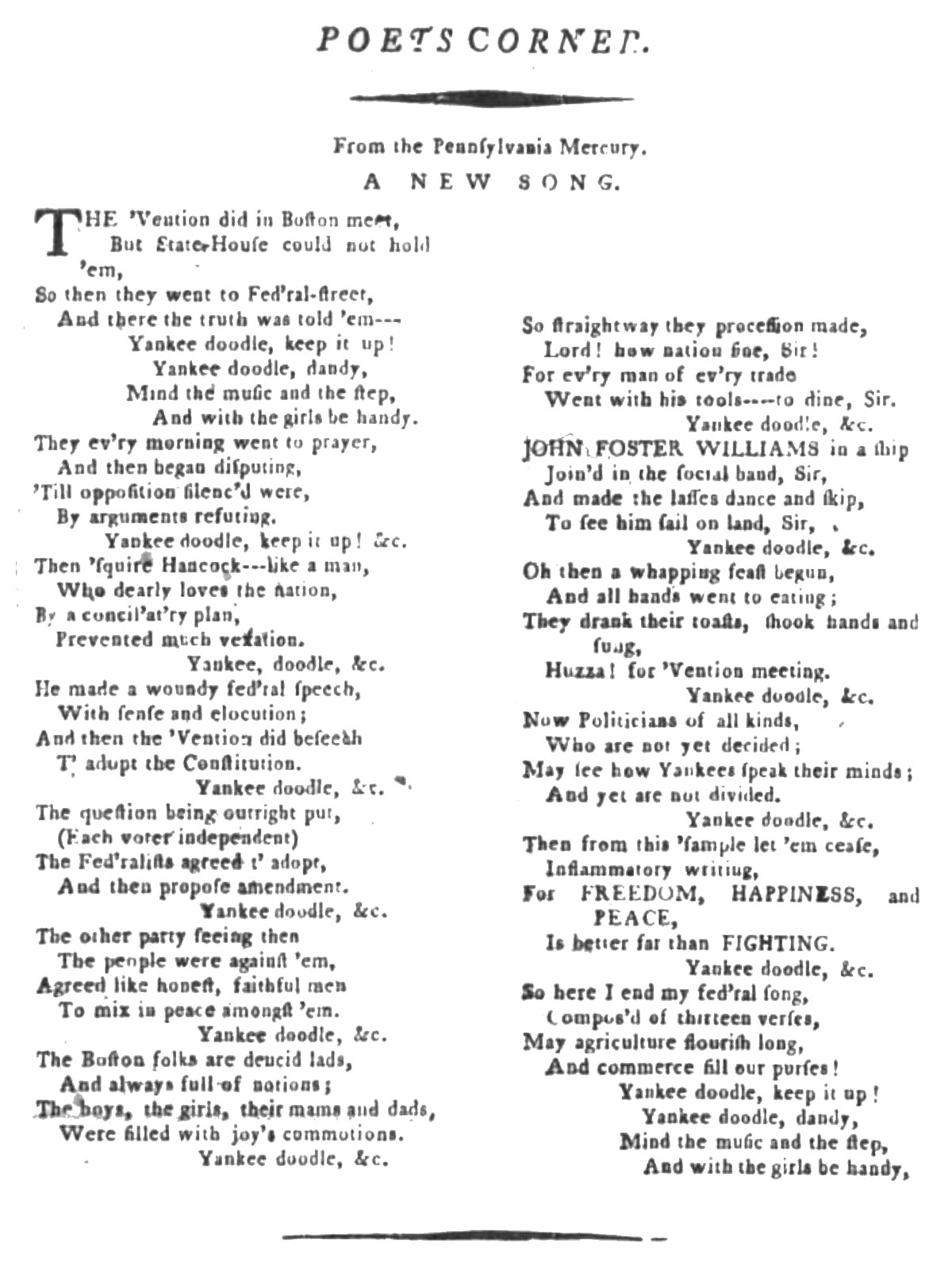

Yankee Doodle has inspired many interesting songs from the era. In 1788 “A New Song” was reprinted “From the Pennsylvania Mercury” in several newspapers, even in Canada. It appears to have been part of the campaign for the ratification of our modern Constitution, or possibly praising its ratification in Massachusetts. The “New Song” ends with:

- Now politicians of all kinds,

- Who are not yet decided;

- May see how Yankees speak their minds;

- And yet are not divided.

- Yankee doodle keep it up!

- Yankee doodle, dandy,

- Mind the music and the step,

- And with the girls be handy.

- Then from this ’sample let ’em cease,

- Inflammatory writing,

- For FREEDOM, HAPPINESS, and PEACE,

- Is better far then FIGHTING.

- CHORUS

- So here I end my fed’ral song,

- Compos’d of thirteen verses,

- May agriculture flourish long,

- And commerce fill our purses!

- CHORUS

That… seems like a good sentiment to end on. Happy New Year. May your Sestercentennial celebrations flourish long, and your purses be filled!

In response to Songs of the American Revolution: Various songs, and the history of the songs, that made the Revolution—sometimes decades later.

Actually, it reads “thd” but I’m nearly certain that’s a typo. Later accounts print it with “the”.

↑The Pennsylvania Ledger article actually gives 1777 as the source, but that has to be a typo given that 1777 predates the actual event! Later reprints refer to 1778.

↑

American history

- The Modern Battle of the Kegs: Anonymous

- A temperance poem as a parody of Francis Hopkinsons’s The Battle of the Kegs, by “Poet laureate of the know nothings”, 1854.

- Padgett Sunday Supper Club Sestercentennial Cookery

- The Sestercentennial Cookery is a celebration of American home cooking for the 250th anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence.

- They Mystery of the Loring Bowl: J. L. Bell

- “I’m delaying the return of CSI: Colonial Boston to discuss this big silver punch bowl from the early eighteenth century.”

American Revolution

- David Bushnell and his Revolutionary Submarine: Brenda Milkofsky

- “How a farmer’s son became the Father of Submarine Warfare during the American Revolution.”

- The Enigma of General Howe: Thomas Fleming

- “He had a reputation as a bold, resourceful commander. Yet in battle after battle he had George Washington beaten—and failed to pursue the advantage. Was ‘Sir Billy’ all glitter and no gold? Or was he actually in sympathy with the rebellion?”

- George Washington to Joshua Loring, 1 February 1777: George Washington

- A letter to Commissary General of American prisoners-of-war in New York, Joshua Loring, about a potential exchange of officers.

Battle of the Kegs

- The Battle of the Kegs: Lieutenant Commander Thomas J. Cutler

- “When David Bushnell heard of the Augusta’s gigantic explosion, it got his inventive mind working.”

- The Battle of the Kegs (January 5th 1778): Eric Sterner

- “The Philadelphia Campaign did not end well for the Continental Army after three separate defeats at Brandywine, Paoli, and Germantown followed by the British occupation of the new nation’s capital. Among other things, however, it would produce an amusing little ditty commemorating an attack on the British on January 5, 1778 for American audiences…”

- The Battle of the Kegs, 1778: Randal Rust

- “The Battle of the Kegs was an incident that took place on January 6, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It was a failed attempt to bomb British ships by fixing explosives to floating kegs. It is most well-known for inspiring Francis Hopkinson to write a song about, which chastised General William Howe for his affair with a married woman.”

music

- 1776•: Sherman Edwards, Peter Stone, and Peter H. Hunt (DVD)

- A fun musical with long interludes of politics.

- Review: Songs of ’76: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “Oscar Brand prefaces and separates each song with a history related to, often tangentially so, the genesis of the song or just the reason he chose the song—some of the songs are from well after the event in question.”

- Songs of ’76: Oscar Brand at Internet Archive (hardcover)

- “A Folksinger’s History of the Revolution… Being a compendium of music and verses, patriotic and treasonous, sung both by the Rebels and the adherents of His Royal Majesty George III.”

- “The Egg” from the musical 1776

- “It’s a masterpiece.”

Yankee Doodle

- Yankee Doodle (Recorded 1910)

- Performed by Billy Murray, Comic Ragtime Songs (Encore 2).

- Yankee Doodle melody

- From a 1930 version of the melody published by C. Bradlee, Boston.

- Yankee Doodle: A Favorite National Air (PDF File, 659.5 KB)

- “For the Piano Forte, published by C. Bradlee, Washington Street, Boston.” 1930.

More American Revolution

- Cherry Valley: A Massacre of the Revolution

- Mel Gibson’s The Patriot is disparaged for the ruthlessness it portrays among the British. But such barbarity certainly did exist. One massacre by British troops is still remembered by the residents of Cherry Valley, New York.

- The World Turned Upside Down

- The legend of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis to Washington at Yorktown says that the band played “The World Turned Upside Down”. It probably didn’t. But we’re going to print the legend anyway.

- Songs of the American Revolution

- Various songs, and the history of the songs, that made the Revolution—sometimes decades later.

- Our lot is cast in this happy land…

- Samuel B. Young’s August 16, 1819, Oration to commemorate the 1777 Battle of Bennington.

- Battles of the Revolution

- Sources from well-known and lesser-known battles of the American Revolution.

More A Sestercentennial Year

- The New Colossus Breathes Free

- There’s nothing wrong with The New Colossus except the way the institutional left has twisted it into meaning the opposite of what it actually says. Emma Lazarus wrote The New Colossus for the exiles of government-sponsored terror to escape their persecutors to a land of Freedom, not for letting their persecutors in to continue the persecution here.

- Padgett Sunday Supper Club Sestercentennial Cookery

- The Sestercentennial Cookery is a celebration of American home cooking for the 250th anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence.

- Cherry Valley: A Massacre of the Revolution

- Mel Gibson’s The Patriot is disparaged for the ruthlessness it portrays among the British. But such barbarity certainly did exist. One massacre by British troops is still remembered by the residents of Cherry Valley, New York.

- The World Turned Upside Down

- The legend of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis to Washington at Yorktown says that the band played “The World Turned Upside Down”. It probably didn’t. But we’re going to print the legend anyway.

- Our lot is cast in this happy land…

- Samuel B. Young’s August 16, 1819, Oration to commemorate the 1777 Battle of Bennington.