Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1927 Electric Refrigerator Menus & Recipes

Also available in print.

This is the second of four addendums I’ve queued up to my three-parter revisiting the refrigerator revolution. That series was originally meant to cover 1928, 1942, and 1947; the latter just barely predated the modern near-universality of home refrigerator ownership. But as I delve deeper into the origins of the home refrigerator/freezer era, it is becoming almost literally the bottomless pit of fascinating fridge finds!

Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Frigidaire, 1928

- Cold Cooking, 1942

- Cold Cookery, 1947

- Kitchen-Proved, 1937

- General Electric, 1927 ⬅︎

- Refrigeration, 1926

There is always something more interesting just around the corner. While wandering an antique mall over the 2024 Thanksgiving holiday, I ran across this 1927 General Electric refrigerator manual (PDF File, 22.3 MB). It looked interesting, but (a) it was unpriced, and (b) it was missing at least one page. It also wasn’t the first printing, which meant I’d need to do some research anyway before buying it.

The Internet Archive has several printings, albeit not the first, which allowed me to compare changes over time. The changes between the third and fourth printings definitely made me want to see the first printing. That wasn’t difficult: there are a lot of copies of this book left, and some of the sellers are even smart enough to include a photo of the indicia page! A quick negotiation over the movement of digital green pieces of paper, followed by several days of impatient waiting before heading on a two-week Valentine’s Day trip, and I very happily came into possession of a copy to read for myself.

It is fascinating. The title is “Electric Refrigerator Menus and Recipes” and the subtitle is “Recipes prepared especially for the General Electric Refrigerator”. Like the Frigidaire manual from a year later in 1928, General Electric treats their refrigerator as literally just like any other kitchen appliance. It is a tool used for cooking.

That year also brought some important differences. Unlike Frigidaire, General Electric’s manual specifically calls itself out as being a manual for an electric refrigerator. GE in 1927 either wanted to play up the electric nature of their refrigerator, or needed to differentiate their product from non-electric refrigerators.

Even more interesting, though, is how much of a wide-open future home refrigerator/freezers had. Even the manufacturers didn’t know what the future held.

As this book is being compiled the electric refrigerator is yet a new invention and the total sum of its usefulness has not in any way been discovered. It has proved that it is an immense improvement over the ice chest that has to be chilled by ice.

It remains for the users of electric refrigerators to continue to find new ways to make it serve them.

“It remains for the users…” much as it remained for the users of personal computers to “continue to find new ways to make it serve them” fifty years later.

The only two activities where the participants are called users are drugs and computers. — Overheard at IETF

Computer manuals in 1977 not only contained computer programs for their users to try; they exhorted their users to try new things. Refrigerator manuals in 1927 did the same thing, but with recipes.

And none of the foregoing is surprising. 1927 was the very start of the refrigerator revolution. According to Eric Chaline in Fifty Machines that Changed the Course of History,

The first self-contained refrigerators appeared in the first decades of the twentieth century, with brands such as Frigidaire, Electrolux, and Kelvinator. However, with units costing more than a family car, the market for refrigerators remained tiny until G.E. introduced the first affordable model in 1927, nicknamed the “Monitor Top,” which gradually reduced in price from $525 to $290.

If you look in this manual, you can see the “monitor top” that gave the fridge its name in the drawings on pages 7, 27, and 32.

The Technology of the Era

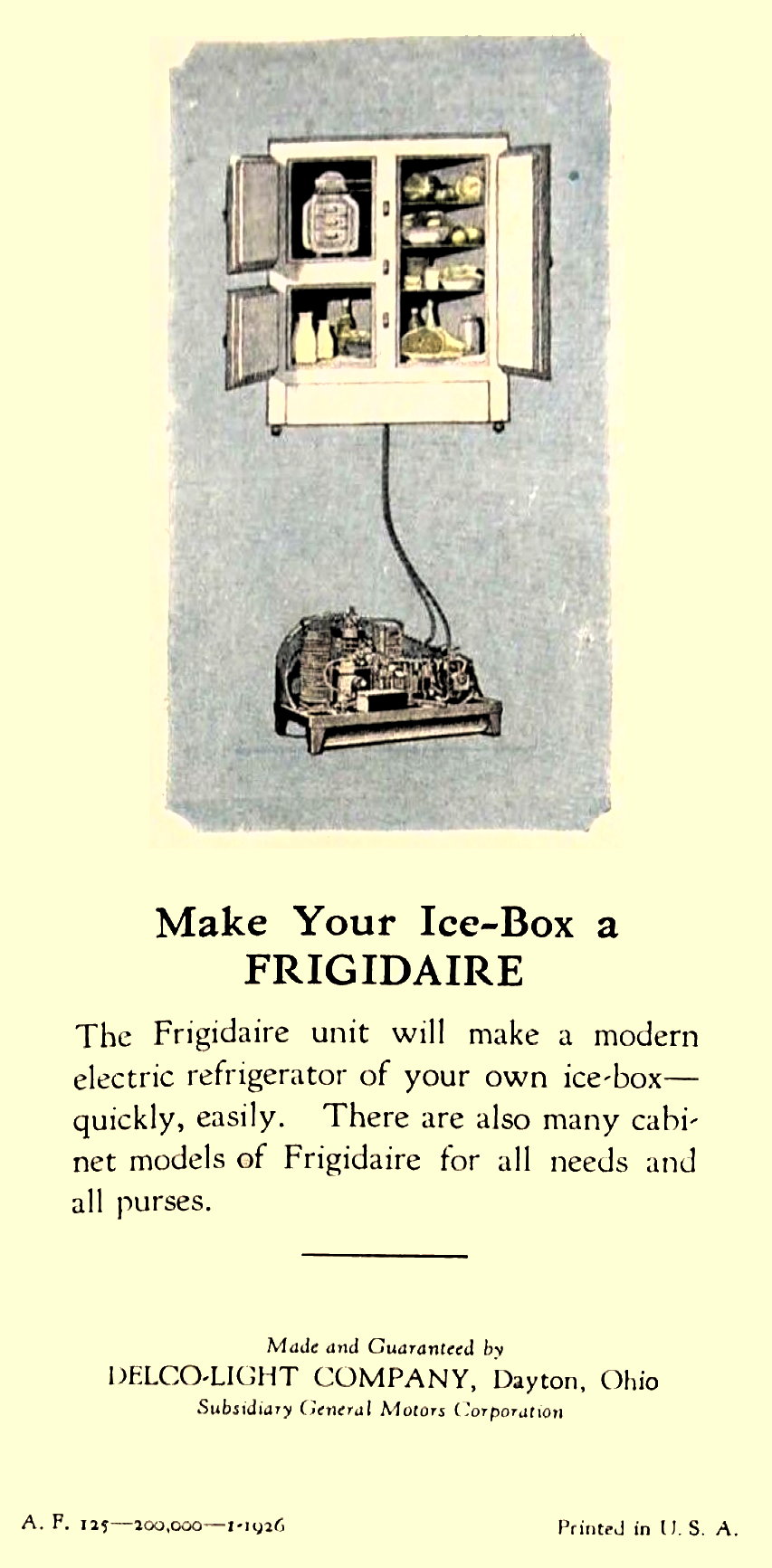

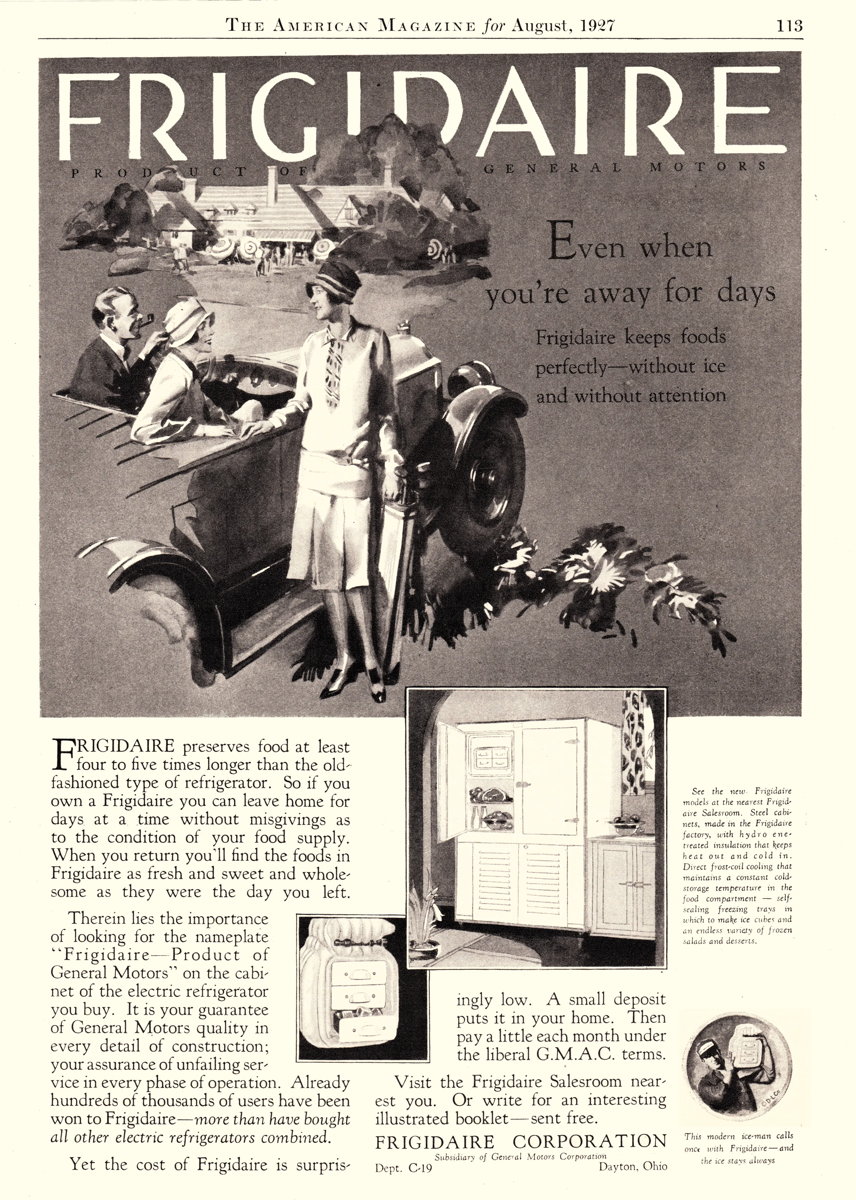

That puts this book right at the start of the refrigerator revolution. As I mentioned in Ice Cream Cookery, Frigidaire had put out a pamphlet in 1926, Frozen Desserts and Salads made in Frigidaire that appears to show a home refrigerator of some kind in the background. I’ve since found a full copy of that pamphlet, and judging from the illustration on the back cover this was for refrigerators in which the cooling unit was in the basement! You could pipe the cold air from the cooling unit into your existing ice box(es) or buy a “cabinet model” from Frigidaire.

As convoluted as that sounds, it was still popular, much in the same way that personal computers before 1977 were popular. Frigidaire claimed “hundreds of thousands of users" in an August 1927 advertisement.

There are two reasons so many copies of General Electric’s manual still exist: one is that, as the first refrigerator this model was wildly popular for at least several years. And the other is that it’s a quality book, designed to be as durable as the refrigerator it accompanied.

Miss Alice Bradley, Principal of Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery, Editor of Woman’s Home Companion, Author.

General Electric treated Electric Refrigerator Recipes and Menus as a real book. Right from the start, they printed it out with the edition1, the month, and the year. It’s rare to see a refrigerator manual like this with the phrase “First Edition” in it. It’s a durable hardcover as beautifully printed as the Frigidaire that would follow it a year later. Like the Frigidaire, it sports a sturdy sewn binding (which is why I was able to scan it without harming it) and quality paper that has lasted the near-century since it was printed.

Also like Frigidaire Recipes, this book has an author, a Miss Alice Bradley, who, like Frigidaire’s Verna L. Miller, was at the time a famous food writer. She was a graduate of the Boston Cooking School (1897), taught at the New York School of Cookery, and took over Fanny Farmer’s school when Farmer died in 1915. She was cooking editor of The Woman’s Home Companion and had her own cooking show and newspaper column.

Another interesting feature of the book is that all of the recipes are numbered. This doesn’t appear to be a very common practice. But it may be, or have been viewed by the GE marketing department as, a mark of quality. The other book I’ve seen it in was the famous and influential La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiar Bene by Pellegrino Artusi. The 1922 version on the Internet Archive was the 25th edition. It was by 1927 a venerable book and probably well-respected among professional chefs. Even today in Italy you still occasionally see recipes referred to by their Artusi number.

It’s also interesting looking at what commercial snacks were available when this came out. Take a look at the Party Menus for Children on page 25: Animal Crackers aren’t surprising, but Marshmallow Bunnies do surprise me a little.

What recipes aren’t in the book is just as interesting. Eggs à la Golden Rod, for example, are listed under Party Menus for Children VII on page 30. It’s a wonderful title. But there is no recipe for it in the book!

Nor are there any sandwich spreads, a staple of later refrigerator manuals. There’s only one cookie recipe, with a note that tells bakers to just use their old cookie recipes. The refrigerator makes them crisper, lighter, and easier:

Most rolled cookies are improved, being more crisp and delicate, if dough is chilled in the refrigerator before rolling. It may be left covered for days and the cookies shaped and baked a few at a time as wanted. They can be rolled thin without sticking and without the addition of more flour.

Most cookie mixtures if packed solidly in a bread pan and chilled over night in the refrigerator can be sliced thin and put on oiled tin pans in less time than is required to roll and cut them.

The refrigerator improves pastries from start to finish. The book’s pastry recipes call for mixing “ice water” into the flour, and for keeping the butter cold. Chilling the butter doesn’t just make it mix better. It ensures that the butter is “free from butter milk”. In the sense used here, “butter milk” is likely the liquid left over after churning cream into butter. If your butter is fresh from the farm, it might well have some “butter milk” remaining in it. Chilling the butter would (further) solidify the butter but not the milk, giving you a more pure butter by letting the milk run off.

A long explanation for something that would have been obvious to a reader in the twenties.

Once the pastry is mixed with ice water and cold butter, it “can be chilled in the chilling unit or directly below it and can be rolled out much more easily than if they were not chilled.”

Something missing from this 1927 book, especially compared to the 1928 Frigidaire book, is alcohol. Neither wine, nor brandy, nor spirits, nor any other obvious kind of alcohol is referred to in this prohibition-era book, even for invalids. It does call for flavoring extracts in some recipes, which as far as I can tell did still contain alcohol during prohibition—and still remained legal.

The book indirectly calls for alcohol by incorporating it from other, non-included recipes such as calling for Newburg Sherry in a Quick Aspic Jelly recipe (recipe 11). There’s also a reference to sherry jell in Frappéd Sherry Milk (recipe 92). As far as I can tell, sherry jell did not contain alcohol. Any invalids who owned a General Electric could not take solace in brandy as did those who owned a Frigidaire a year later!

Because the Internet Archive has the third printing I was able to compare changes. Most of them are changes in kerning, hyphenation, and publisher name. The latter is obviously worth remaking the plates for, but the kerning and hyphenation changes are not at all obviously worth the trouble.

The only thing remotely like an error corrected was the period (or dot) on page 86. What was the reason for changing the kerning in various places? It’s the kind of ridiculously slight change that might happen accidentally in our era when moving from one version of a page layout software package to another. Was it somehow related to a printer change? Were some of the plates slightly damaged and needed remaking?

I only fully compared the “First Edition (PDF File, 22.3 MB)” to the “Third Edition”. Later changes are more interesting if less mysterious. In the first and third printings, the penultimate paragraph of Alice Bradley’s introduction reads:

The owning of such a refrigerator is a form of health and happiness insurance which every homemaker in America should have the privilege of enjoying. For those of you fortunate enough to own one, the information on the following pages is intended to make its use as pleasant and valuable as possible.

The September 1928 fourth printing has exactly the same introduction, except that the text I’ve bolded has been removed, and the now independent subsequent phrase reworded:

The information on the following pages is intended to make the use of this newest model as pleasant and valuable as possible.

The removal of the line about being fortunate enough to own a new modern refrigerator is fascinating, but without further clues mostly opaque. It’s easy to conjecture that refrigerators were becoming ubiquitous enough that you no longer had to be fortunate to own one—or at least that General Electric didn’t want to make that impression!

But there’s something else significant about that line that isn’t as immediately obvious. They didn’t write, as modern manuals might, about being fortunate enough to own a General Electric refrigerator. They wrote about being fortunate enough to own any electric refrigerator. I don’t think this was a chance phrasing. They’re even more explicit about the importance of refrigerators in general later. The questions-and-answers Concerning Refrigerators section asks “What is an Adequate Refrigerator?”

An adequate refrigerator is large enough to meet the usual needs of the family for storage of food and ice; cold enough to keep food sweet for several days; so constructed that it is easy to clean; so placed that it is conveniently accessible to the housewife or the cook when preparing and clearing away the meals.

Most Electric Refrigerators meet all these needs without the inconvenience of bringing in ice and carrying off the water as it melts away.

The entirety of Concerning Refrigerators is about “Why a Refrigerator?”, not “Why a General Electric Refrigerator. General Electric isn’t so much trying to convince you to use their electric refrigerator. They’re trying to convince you use electric refrigerators in general!

The Chilling Unit—The temperature of the interior of the chilling unit of a General Electric Refrigerator is below the freezing point. This unit is used for freezing ice, for freezing desserts and salads, and for chilling things which are served very cold or wanted very quickly. The space immediately below the chilling unit is much colder than any section of an ice refrigerator. The temperature of the remaining space is several degrees lower than in ice refrigerators.

Electric refrigerators are much better than ice refrigerators that require bringing in ice and carrying off water, and don’t even keep food cold despite all that work.

Since it is kept cold electrically, it need not be near an outside door, nor placed for the convenience of the ice man. All that is necessary is a convenience outlet into which its long cord can be plugged. The most convenient place in the pantry or the kitchen is the place for the General Electric Refrigerator.

Mind you, given the competition in 1927, they probably felt that once a customer made the decision to buy an electric refrigerator, the benefits of a General Electric were overwhelming. In 1927, everything else was obsolete, either too expensive or too complicated.

Like the 1942 Montgomery Ward book, General Electric was also explicit about the dangers of using cold weather to keep food safe.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, nature can furnish you with adequate refrigeration only a few days during the year. To keep milk, butter and other foods palatable and in a safe condition refrigeration is necessary in both summer and winter.

The book also references the “scalding” method of using evaporated milk that I’ve written about before.

Evaporated milk must be scalded and then chilled before it can be whipped like cream… it can replace the cream in any mousse or ice cream which contains gelatine.

I still have no idea if evaporated milk needed scalding because it was different than modern evaporated milk, or if refrigerators were just not cold enough to make evaporated milk whippable without scalding it first. Or if scalding was just a holdover from the pre-refrigeration era and recipe writers hadn’t yet realized it was no longer necessary.

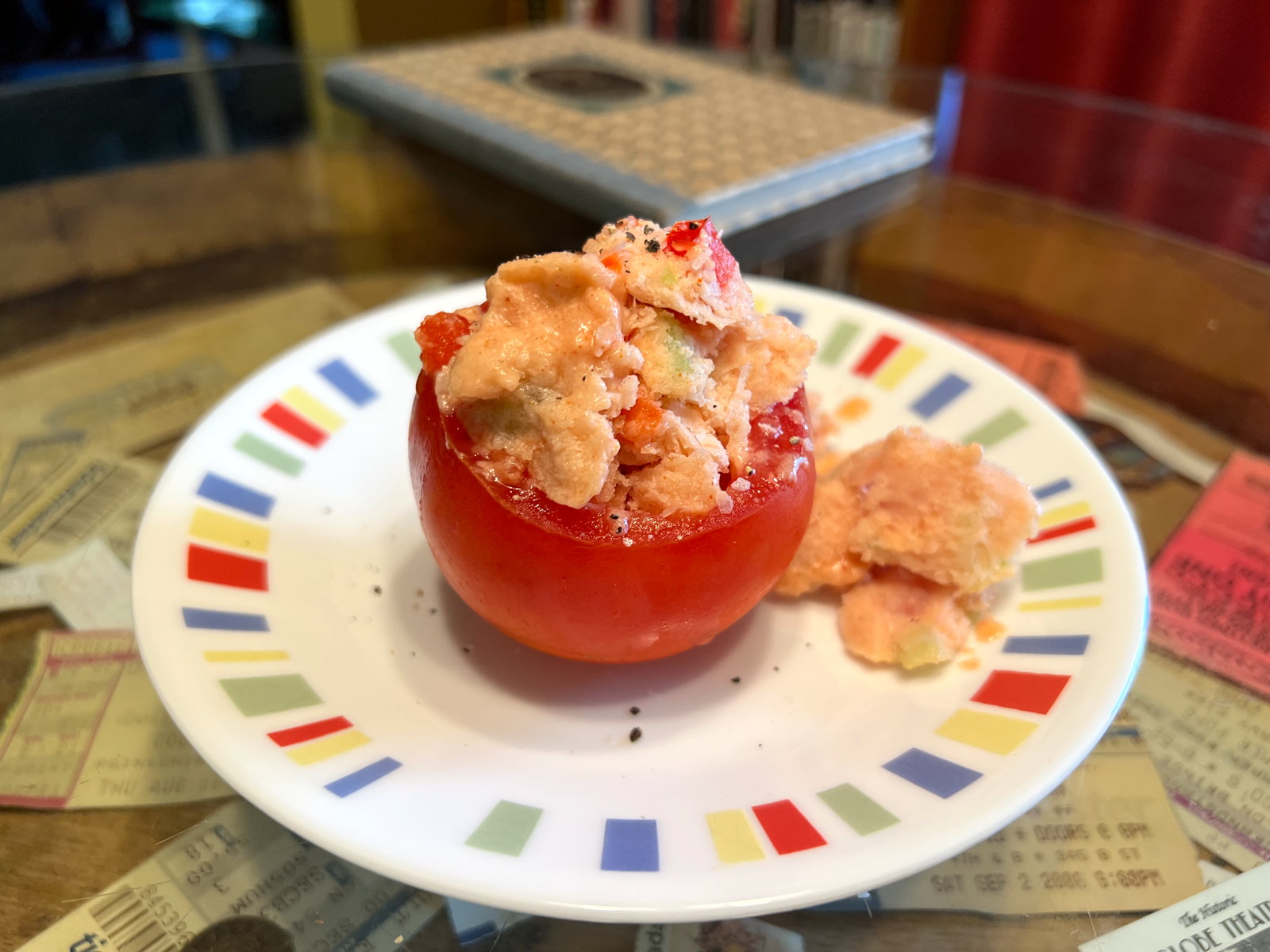

Many of the recipes are odd, and, if you keep your wits about you, even fun. The Tomatoes Stuffed with Frozen Salad was very alien to me. If the title didn’t literally contain the phrase “frozen salad” I would have assumed that I was reading the instructions wrong. Since the dish is meant to be made up ahead of time and constructed as needed, the frozen salad does need time in the refrigerator to soften before scooping out. Otherwise, it’s hard as a rock and unscoopable.

I expected the texture of frozen vegetable salad to be horrible. But it was fine, as was the flavor. Since it’s a filling to stuff a hollowed tomato, it appears to have been meant to be eaten with a knife and fork. It would be very nice with a good crisp and tender steak.

And, likely the important thing, it looks elegant. The colors are right for a sidetable spread or buffet. It might even taste better after it’s been sitting on a buffet table for half an hour or more.

The Rice and Pineapple with Cream was a much nicer treat. It’s a rice pudding more than a rice salad. The rice and milk are cooked over hot water until the milk is completely absorbed, then rubbed through a sieve, then mixed with sugar, pineapple, and whipped cream. Except for the rubbing through a sieve bit it’s dead easy. And the sieve is unnecessary if you have a modern appliance called a “blender”.

Rice and Pineapple with Cream

Servings: 4

Preparation Time: 1 hour, 30 minutes

Miss Alice Bradley

Electric Refrigerator Recipes and Menus (PDF File, 22.3 MB)

Ingredients

- 1 cup milk

- ¼ cup rice (consider arborio)

- 2 tbsp sugar

- ¼ tsp salt

- 1 cup crushed or chunked pineapple

- 1 cup cream

- 5-6 candied cherries

Steps

- Scald the milk over boiling water.

- Add the rice and cook over simmering water for about 50 minutes, until tender and the milk is absorbed.

- Add sugar, salt, and pineapple, and blend until roughly smooth.

- Chill in refrigerator.

- As near to before serving as is reasonable, beat cream to stiff peaks

- Fold cream into rice.

- Pour into five or six cocktail or parfait glasses.

- Top each with a candied cherry.

- Chill until needed.

I want to make it again with rhubarb instead of pineapple.

The Walnut-Nougat Ice Cream is also a winner. In modern terms we would call it a walnut brittle ice cream. The ice cream is made with a custard of egg yolk and gelatin—spelled gelatine as in the 1928 Frigidaire manual. I initially thought that the brittle part of the recipe was awfully small but, having made it, I suspect no one ever made it in that amount. In the future I plan to make a double or even triple batch and keep the extra as candy.

The brittle recipe is made differently than modern brittle, using a technique I see a lot of only in older books. Take sugar, heat it until it melts, and then add the walnuts. Other than using black walnuts I made the recipe straight. And it’s possible that black walnuts were the default in 1927.

The Lemon Cream Sherbet’s instructions for using gelatin were a bit confusing:

Add gradually to 2 teaspoons gelatine soaked and dissolved in 2 tablespoons cold water (How to Use Gelatine, page 39).

The instructions on page 39 say to do the standard bit of soaking the gelatin in cold water and then heating it in a pan of boiling water until it dissolves which is what I did. I’m still not sure it’s what the author meant.

An interesting variation is to use sour cream instead of whipping cream in the Sherbet. The instructions say to use “½ cup cream, sweet or sour”. Unlike sweet/sour milk, in modern usage those two items are very different, which makes me wonder if this means what I interpreted it as, which was to use either whipping cream or sour cream.

I tried each of those variations, and each turned out great. They obviously each made very different sherbets.

Refrigerator manuals would quickly evolve beyond Electric Refrigerator Recipes and Menus (PDF File, 22.3 MB). The Frigidaire company would change the focus from electric refrigerators to Frigidaire refrigerators, even to just the word Frigidaire, so reminiscent of Macintosh in the modern computer era.

While it was refreshing to not have to pretend to be excited by non-dessert recipes, the focus of “cold cooking” would soon expand beyond desserts. Recipes of all sorts would get added to these manuals as companies received feedback from refrigerator users who did indeed “find new ways to make it serve them.”

And of course, over the next twenty years—from 1927 (PDF File, 22.3 MB) to 1947—these amazing new appliances would go from something you’re fortunate enough to own, to something you own by default. Much like the difference between owning a computer in 1977 vs. owning a computer in 1997.

I’ve republished this book as both a downloadable PDF (PDF File, 22.3 MB) and a paperback.

In response to Revolution: Home Refrigeration: Nasty, brutish, and short. Unreliable power is unreliable civilization. When advocates of unreliable energy say that Americans must learn to do without, they rarely say what we’re supposed to do without.

These are really printings, not editions, and I will refer to them as such from this point on except when quoting the book.

↑

Download

- Electric Refrigerator Recipes and Menus: Miss Alice Bradley at Lulu storefront (paperback)

- A facsimile reprint of the manual and recipe book for General Electric’s groundbreaking 1927 refrigerator.

- Electric Refrigerator Recipes and Menus (PDF File, 22.3 MB)

- A 1927 guide to using a home refrigerator/freezer “Specially Prepared for the General Electric Refrigerator” by Miss Alice Bradley, Principal of Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery.

- Four New Ices and an Ice Cream Cookery

- Philadelphia Ice Cream, Walnut Nougat, Lemon Cream Sherbet, and Cranberry Ice. Four more new no-churn ice creams and desserts for Summer 2025. And, a book collecting all my favorite no-churn ice creams if you’re interested!

General Electric

- Electric Refrigerator Menus and Recipes (3): Miss Alice Bradley at Internet Archive (ebook)

- General Electric’s 1927 dessert book for home refrigerators, 1929 third printing.

- Electric Refrigerator Menus and Recipes (4): Miss Alice Bradley at Internet Archive (ebook)

- General Electric’s 1927 dessert book for home refrigerators, 1928 fourth printing

- Electric Refrigerator Menus and Recipes (5): Miss Alice Bradley at Internet Archive (ebook)

- General Electric’s 1927 dessert book for home refrigerators, 1929 fifth printing.

history

- Alice Bradley

- “Alice Bradley (1875-1946) was a pioneering cook and educator. She tested recipes for Fannie Farmer, taught at Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery, and eventually led the school.”

- Fifty Machines that Changed the Course of History: Eric Chaline at Internet Archive

- “From Stephenson’s ‘Rocket’ to Sony’s ‘Walkman,’ mechanical devices have helped to define our culture and to transform the way we live our lives.”

- La Scienza in Cucina e l'Arte di Mangiar Bene: Pellegrino Artusi at Internet Archive (ebook)

- “Manuale pratico per le famiglie.”

- Review: The Joy of Cooking: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This edition of Irma Rombauer’s influential book is old enough to be at the dawn of chocolate chips.

refrigerators

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1928 Frigidaire

- The 1928 manual and cookbook, Frigidaire Recipes, assumes a lot about then-modern society that could not have been assumed a few decades earlier.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1947 Cold Cookery

- The 1947 Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest reflects not just increased access to electricity but also the end of a second world war.

More Refrigerator Evolution

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1928 Frigidaire

- The 1928 manual and cookbook, Frigidaire Recipes, assumes a lot about then-modern society that could not have been assumed a few decades earlier.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1947 Cold Cookery

- The 1947 Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest reflects not just increased access to electricity but also the end of a second world war.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1937 Kitchen-Proved

- Refrigerators started to take off during Prohibition, and became ubiquitous following World War II. This Westinghouse refrigerator manual and cookbook gives us a glimpse at home refrigerator/freezers in the Great Depression.

- My Year in Food: 2025

- My year in food extended from 1776 to 2026, from San Diego to Barcelona, and from Texas to Michigan. I also made several vintage books available for you to download!

I've long had a passing interest in old technology, whether it be gadgetry or manufacturing, so I enjoyed browsing your research on refrigerators.

More to the point, my grandfather worked for the Jefferson Ice Company in Chicago from 1911 to 1941; superintendent from 1920 on. Their ice plants evolved into building-sized refrigerators. Customers ranged from families to restaurants, buying ice for commercial use typically in standard half-blocks of 210 pounds, or in smaller chunks for homes. Even during the Depression, ice was a necessity to keep one's meat and other perishables from summer heat; and movie theaters advertised their air conditioning (by ice).

Robert W. Franson in San Diego at 11:27 p.m. January 24th, 2026

FaI9T

Wonderful anecdote on your site, Robert! My grandfather worked for an ice company as a young man. He said it was almost literally back-breaking work.

Jerry Stratton in Texas! at 12:13 a.m. January 25th, 2026

yFmrE