Astro City: Hope to Hopeless in the Big City

In his first Astro City collection, Life in the Big City, Kurt Busiek set himself a very noble goal:

The superhero has been dissected, analyzed and debunked, his irrationalities held up to the light… to show them for the unworkable Rube Goldberg machines they are… it’s almost become impossible to present a superhero who does what he does without being emotionally unstable, incapable of dealing with reality… We’ve been taking apart the superhero for ten years or more; it’s time to put it back together and wind it up, time to take it out on the road and floor it, see what it’ll do.

Having this goal in mind—unstated in the uncollected single issues—made the debut of Astro City a real breath of fresh air in superhero comics. I remember avidly searching out each issue and then each collection as Busiek moved from Superman to Batman to Marvel, each with a new world of wonderful stories combining the charm of the old-school with the art and storytelling of the new.

Unfortunately, Busiek found it very hard to transcend his era; his desire to “floor it” never exceeded deconstruction’s 55 mph limits. That makes even the best of these books not stand up well to re-readings. But what Busiek wanted to do was so necessary that it took me, at least, a long time after I stopped looking for the collections to remove them from my want list. I wanted to believe long after I lost faith.

Even the first collection, a take on Superman, amounts to mostly deconstruction rather than reconstruction. At best it’s deconstruction from a different angle. Few writers have really grokked Superman. Outside of Maggin! and Morrison• even those writers who don’t prefer a Moore-like destructor of worlds still don’t understand the genuine balanced goodness underlying Superman, his upbringing, and the Metropolis he inhabits.

On the surface, that Busiek isn’t up to the level of a Maggin! or Morrison is forgivable. But he needed at least to try to reach those stars in order to achieve his noble goals. Instead, rather than a Superman so powerful he cannot but fall to the temptations of power, Busiek’s Samaritan is so good he cannot possibly balance his life as a hero and reporter. Asa Martin works at a newspaper just as Clark Kent does. But Martin is not a reporter. He’s a fact checker, isolated in his private, locked office, never interacting in the newsroom as Kent so famously did. There is no Lois Lane, no Jimmy Olsen, no Steve Lombard for Asa Martin.

There is never hope.

Martin’s day job is little more than as a human computer—he literally sets a computer to do his day job for him when he goes off to save the world. Even his saving the world is computer-driven, with his computer telling him where he is needed most. The reason he has no Lois, Jimmy, or Steve is that he has no time for them. Every waking hour is dedicated to saving others. Samaritan, unlike Superman, can only truly live “in dreams”—the title of the opening issue. There’s a redemption of sorts in the final story in which he’s forced by his Honor Guard colleagues to take time out for a date. But as humorous as “Dinner at Eight” is, it highlights just how emotionally unstable Busiek’s powerful heroes remain.

The best story in Life in the Big City is a reporter—not Asa because, remember, Asa isn’t a reporter—describing how he lucked into a massive scoop early in his career. He witnessed a major conflict among the super-powered that nobody else knew about. His editor forced him to cut his article about it practically to the equivalent of “mostly harmless”. Over his own now-long career, the reporter has come to understand that those cuts were right. They were right because they cut his big scoop down to only the verifiable facts. Even what he himself observed is untrustworthy unless there is corroboration.

“The Scoop” is a story about newspaper as superhero, as much a fiction as a visitor from another planet acquiring powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men. But, unlike Samaritan’s life, “The Scoop” at its core is a life to aspire to, both in reality and as wishful thinking. No one without a savior complex would want to live the unbalanced life of Samaritan as depicted in “In Dreams”.

These are all good stories. It’s fun to read them. But it’s also disappointing to read that introduction and realize how much Busiek’s superhero stories missed their lofty goal.

And just before I’m out of range, I hear her laugh quietly to herself, and whisper, “There’s always hope.”

“There’s always hope.”

Well, there is.

In the second Astro City collection, Confession, Busiek proceeded from Superman to Batman. And The Confessor was a wonderful Batman. Confession may be an even better read than Life in the Big City. There’s so much more potential to The Confessor than there was to Samaritan.

The Confessor operates at night to Samaritan’s day, lives in ruins, and has just taken a young sidekick fresh from the orphanage. While his heroic persona relies on mysticism, what he emphasizes to young Brian Kinney is detection, a scientific approach to crimefighting, watching patterns for anomalies from a central computer room in a cavernous lair. The Confessor is, in fact, so close to Batman as to be an inside joke, only revealed to the reader at the end—but in typical Batman fashion treated as a solvable mystery for the reader throughout, just as it’s treated as a solvable mystery for Brian Kinney.

There are always lies.

I don’t buy it. It’s more than that. You wanted someone you didn’t have to lie to.

But Confession is also the dark side of superheroing in almost every way. Superheroing is a thankless task. The public turns against them over unsolved murders, and the government requires them to register as superheroes. It’s a story that Alan Moore did much better in Watchmen. Which, again, it’s not a strike against Busiek that he’s not an Alan Moore. But this main storyline doesn’t even begin to describe how dark Astro City really is.

Most of these collections feature a stinger only slightly related to the overall arc. The stinger in Confession humanizes the most inhuman of Astro City’s heroes, The Hanged Man. A man has literally lost his wife and their life together after a superheroic conflict that resulted in the recreation of the timestream. The recreation was flawed, resulting in his then-wife never existing. She has been erased from the world and from his memories. But their love was so powerful that deep in his soul he suffers that loss. And he doesn’t know why he’s in such soul-searing pain.

Not only would you not want to be one of Busiek’s superheroes, you wouldn’t even want to live in that world. Despite the many stories in this series about how inspiring living in Astro City is, the price you pay is a lot more than the occasional destruction of a city block or finding out that your tenant was the vanguard of an alien invasion. The price is literally your soul.

The Hanged Man stinger is an emotional story—it really is a stinger—about a lost happy past, so deeply lost that it no longer even exists. It’s reminiscent of Grant Morrison’s• ending to the Martian invasion in JLA. But Morrison’s punishment was meted to a supervillain. Busiek’s story highlights just how punishing, at a deeply emotional level, life in the world of Astro City would be even for non-heroes.

- August 20, 2025: Astro City: Tarnished Heroes, Local Villains

-

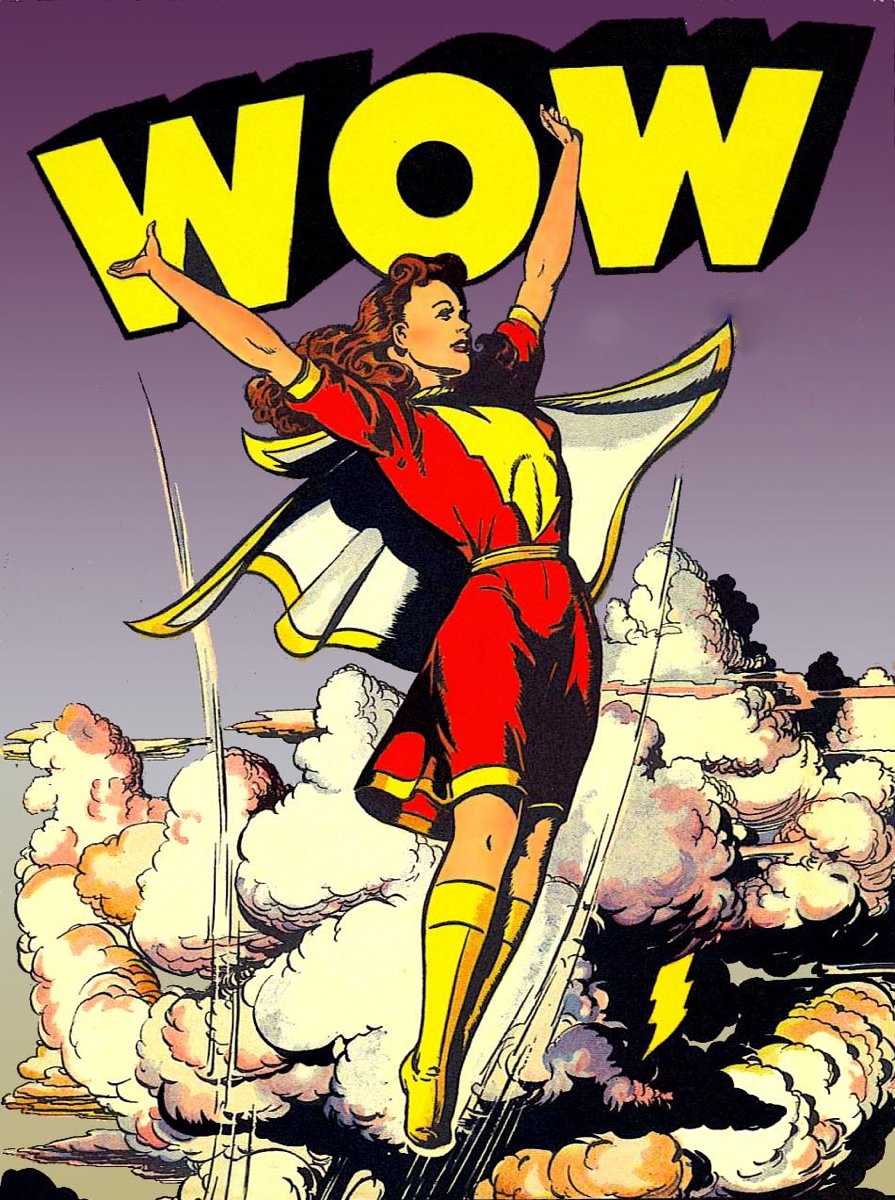

Mary Marvel demonstrates the joy of flight. This seems to be what Busiek was initially striving for, but gave up on.

Addressing the weird impossibilities in superheroes and superhero worlds deconstructively isn’t necessarily a bad idea, and some of the stories are in fact passably decent, with even better characterization than you normally get from deconstructive stories. Busiek’s a good writer. But the deconstructive stories he ended up writing were far easier than the reconstruction of the superhero that he set out to do. That failure is more disappointing than the stories are enjoyable.

Probably the worst and best example of this comes in Local Heroes, the fifth book in the series. The third book, Family Album, provided a brief respite of sorts. It took on a topic that superhero comics rarely do: family. On the other hand, it did the same for the family that the series had so far done to being a superhero or just living in a superhero world: it showed the insurmountable problems such a world creates for normal family life, foreshadowing the problems of justice in Local Heroes. In Busiek’s telling, even a golden-age world of superheroes is necessarily a world of existential loss.

The frame in Family Album followed a normal family moving to Astro City—and getting caught in the family dynamics of the gods themselves. The main story involved Jack-in-the-Box attempting to maintain a family life in a world not just of superheroes but of, again, time-spanning superheroics. It’s up-front about the fears of fatherhood, of what happens to your children when you’re gone, of how children embody multiple potentials. In a superhero world those infinite potentials are real, and they bring infinite pain.

The Junkman story in Family Album follows an old man who is unable to share his accomplishments: the Junkman had no family. In a normal world, this would be the story. In a superhero world, he creates a complicated scheme to ensure that someone will appreciate his life. A world of superheroes creates loss, and in a world of superheroes, loss creates more loss. The pebble rolls downhill and takes out a city.

Tarnished Angel is Jim Rockford meets Marvel. But unlike Rockford, Busiek’s protagonist really is a loser. He never amounts to anything, not even at the end. I’m sure that’s the point, and it was moderately enjoyable reading once and then again now as I’m going through my old comics. But even at its darkest, the explicit point of Astro City was the joy of it, like that old drawing of Mary Marvel flying into the sky with a heavenly smile. Not only does Tarnished Angel not have that joy, it doesn’t have anything to replace it with, either.

- All-Star Superman•: Grant Morrison (paperback)

- A marvelous mythification of all the best that is Superman.

- FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- V, Veidt, and Constantine are very much the same person, each ushering in a new era of human greatness through their own devious means. Even Promethea and Faust, and Moore’s interpretation of Jack the Ripper, share that vision to a lesser extent. What do these five faces of the same man mean?

- Review: Confession: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The second Astro City collection progresses from Superman to Batman, and from the light to the dark in the Big City.

- Review: Life in the Big City: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Kurt Busiek set out to reconstruct the joy of the superhero, but fell back on the emotionally unstable tropes of the deconstruction era.

- Superman: Last Son of Krypton

- “Last Son of Krypton” explores the responsibility of power and the side-effects of universal good deeds through the super-powered adventures of Superman.

More Astro City

- Astro City: Tarnished Heroes, Local Villains

- The contradictions of a superhero world require that you either ignore them or love them. You can never analyze them.

More Kurt Busiek

- Astro City: Tarnished Heroes, Local Villains

- The contradictions of a superhero world require that you either ignore them or love them. You can never analyze them.

More superheroes

- Mighty Protectors release: Villains & Vigilantes 3.0

- As of today, you should be able to buy both the PDF and the print version of Villains & Vigilantes 3.0: Mighty Protectors. It’s a worthwhile purchase.

- Superman vs. the X-Men

- Superman Returns wasn’t as good as I’d been hoping for, but it was very good, and much better than X-Men 3.

- Batman Begins

- A surprisingly good film that marries comic book sensibilities to the big screen in a way that uses and improves the strengths of each. This is the best Batman film ever, and a fine addition to the new series of superhero films.

- Superman: Last Son of Krypton

- “Last Son of Krypton” explores the responsibility of power and the side-effects of universal good deeds through the super-powered adventures of Superman.