Farming hatred on social media

This is just a quick update on why “engagement algorithms” really mean farming anger: that is, what the financial stakes are that encourage artificially inflating engagement. Or at least, it started as a quick update. It quickly went off into the fields of effective advertising, and the ancient debate over eyeballs vs. sales.

Several social media sites reward people for delivering eyeballs—that is, for drawing in viewers and readers. Just as Facebook has discovered, one of the easiest ways to get eyeballs and to keep eyeballs is to encourage rage and hatred. The common term for this is “rage baiting”. It’s become such a common practice that it’s already progressed, language-wise, to a single-word contraction, “ragebaiting”.

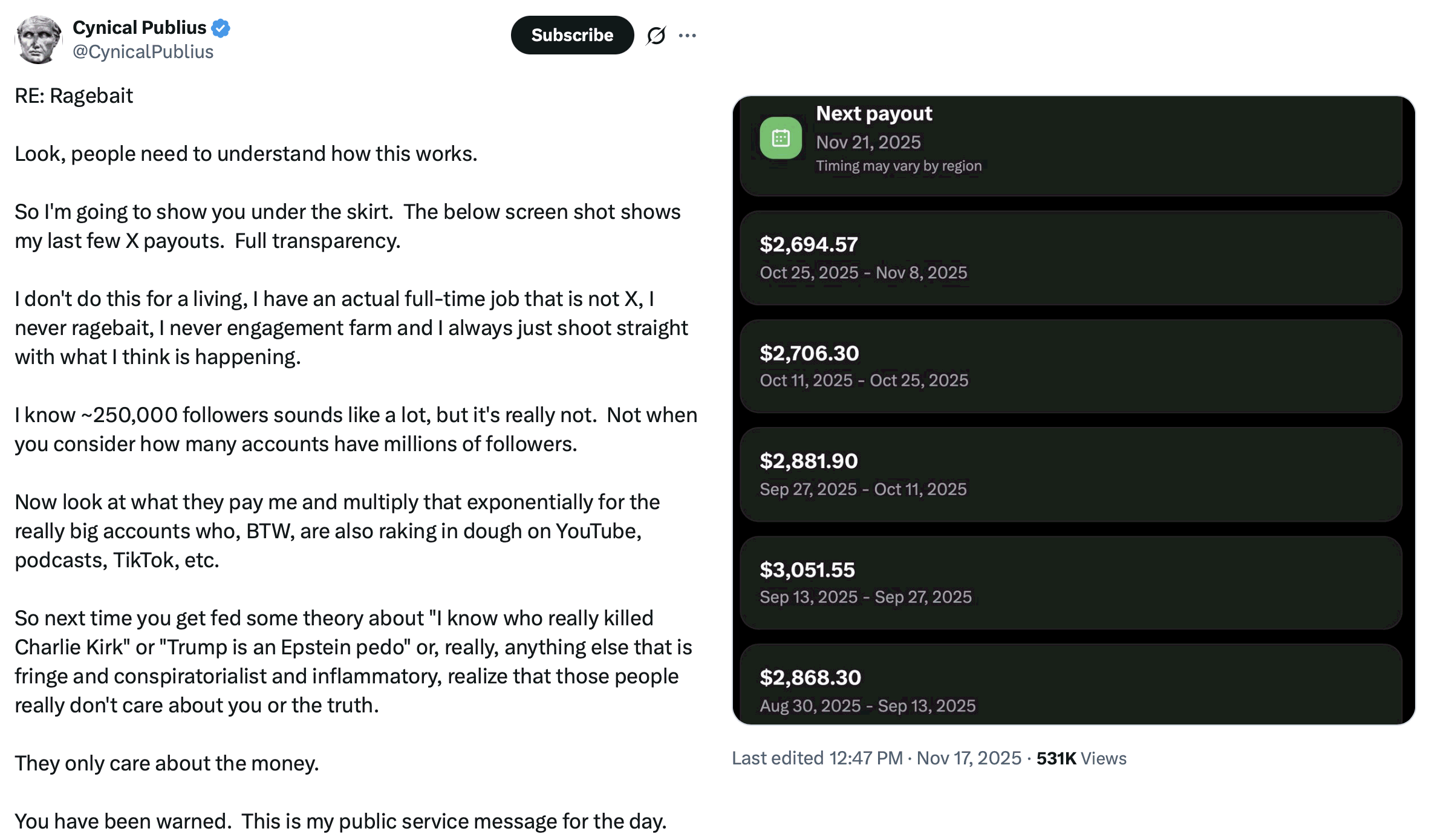

This is what Facebook’s algorithm is designed to encourage, and this example (from X, not Facebook) is the first concrete example I’ve been blessed to find describing how much money is involved. I couldn’t find anything like this when I wrote Facebook is designed to kill relationships.

When you look at these numbers, remember that they are basically affiliate payments. When affiliates are linked directly to sales, such payments run from a fraction of a percent to, at the very high end, four percent, which would mean multiplying by anywhere from twenty-five up to two hundred to get the actual gross profits involved. But social media posts aren’t generally tied directly to sales, only indirectly as delivering eyeballs of potential sales.

Much as the purpose of television shows on broadcast television was to draw in viewers to watch television ads, the purpose of posts on social media is to draw in readers to watch Internet ads. Very few of the viewers or the readers actually convert into buyers. So you’d have to multiply again by two and probably much more for the actual figures involved on X’s side of the ledger.

As Cynical Publius wrote, with only a few hundred thousand followers he’s on the low end of the market. There is a lot of money at stake here, a lot of money to be made focusing our attention away from what matters and toward social media.

This is all that you and I are to social media sites such as Facebook, YouTube, and even X: crops of eyeballs to sell to advertisers. Crops that the current social media sites believe can most easily be raised by rage and hatred.

That’s why the algorithm does what it does, the way it does. If social media platforms can keep us hating, can keep us angry, then they can keep us watching and reading. I focused on FaceBook originally because FaceBook is ostensibly a place for family and friends to interact. Which means that as long as FaceBook follows this strategy they exist mainly to incite rage and hatred between family and friends. At least on X and YouTube the rage and hatred is mostly between strangers.

There are other ways to sell advertising, and I can’t imagine but that at least some advertisers would prefer less divisive means of gaining our attention. Because while rage and hatred unquestionably bring in eyeballs easily, quickly, and in great numbers, how much do they actually sell? Angry people are busy people, venting their anger on the invisible enemy beyond the screen. They don’t have as much time to stop and smell the product that happy people have.

That is the ultimate point of the eyeballs, after all: selling the product. Making a potential customer into an actual customer by convincing them that the product is worth paying for. It’s why old-school advertisements were as likely to be feel-good ads as they were to be feel-angry.

For every you’re being cheated by our evil competitors ad, such as the classic where’s the beef from Wendy’s, there would be an aspirational ad, an I’d like to teach the world to sing. For every 1984 won’t be like 1984 there was a Clydesdale Christmas.

Rage and hatred run the real risk of convincing people that your industry is corrupt and not worth the trouble. Raging viewers, viewers with a hatred for part of your industry, are going to be more difficult to convince that your product—a product within an industry the viewer now feels hatred for because of your advertising or placement—is a positive and worthwhile thing, something worth going out and spending money on.

This is old knowledge. It’s been part of the give-and-take of advertising practices since advertising began. David Ogilvy wrote about it in different terms in his wonderful Ogilvy on Advertising. Disparaging ads risk confusing potential customers. Viewers often come away with better feelings toward your competitors and worse feelings for you. After all, you’re the company being disrespectful. You’re the angry one, and that makes you “less believable”, which can reflect on your product.

There is a tendency for viewers to come away with the impression that the brand which you disparage is the hero of your commercial.

Ogilvy had a great story about focusing on eyeballs rather than selling. Testing for recall, he wrote, “is for the birds”. There doesn’t seem to be any relationship between recall and sales in general; and in specific, some kinds of ads, such as with celebrities, “usually score above average on recall and below average on changing brand preference.” Further,

It is too easy for the copywriter to cheat. ‘When I want a high recall score,’ says my partner David Scott, ‘all I have to do is show a gorilla in a jockstrap.’

I’m pretty sure both Ogilvy and Scott would call rage farming “cheating”. Its delivery of eyeballs goes unquestioned. This doesn’t mean it’s real; I’m not aware of any research that rage baiting brings in more attention than positivity. But even if it does, it is very unlikely that rage baiting delivers the kind of attention that results in sales for advertisers.

Even Wendy’s understood this. Their “Where’s the Beef” ad was as light-hearted as an annoyingly angry ad could be. As the ad campaign progressed, they tried very hard to make it funny, and even downplayed the complaint. But I don’t think they ever were able to shake the feeling, especially when the old lady rushed all over town harassing other fast food joints, that the real heroes of the ad were Wendy’s competitors. By the end of the campaign it was the other fast food joints that were clearly the underdogs, unfairly hassled by this crazy old whiner.1

This is one of the things that Network was about. Union Broadcasting System executive Arthur Jensen realized that Howard Beale’s anger would bring in eyeballs. He did not realize until later that angry eyeballs are not necessarily profitable.

Nor that it is very difficult to dismount that tiger once it begins raging.

In response to Facebook is designed to kill relationships: “The algorithm” is designed to cause strife, because strife increases eyeballs on ads.

And depending on how “recall” is measured, a high-recall ad isn’t necessarily even boosting the recall of your product. “Where’s the beef” is obviously a high recall ad: I remembered it decades later when writing this post. But until I went and found a video of an ad in the campaign, I remembered it as being from Arby’s.

↑

- Network and The Running Man in 2025

- One movie from the seventies and one from the eighties remain far more relevant than their contemporaries—and it’s the silliest that remains most relevant. We are living in Heinlein’s Crazy Years.

- I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing

- “Coca~Cola commercial, 1971, 2020 restoration.”

- Macintosh 1984 commericial

- Macintosh’s 1984 ad riffing on 1984. “Today we celebrate the first glorious anniversary of the Information Purification Directives. We have created for the first time in all history a garden of pure ideology, where each worker may bloom, secure from the pests of any contradictory true thoughts.”

- Original Budweiser Clydesdale Commercial

- “The Original Budweiser Clydesdale Commercial with ‘Here Comes the King’.”

- RE: Ragebait: Cynical Publius

- “Look, people need to understand how this works. So I'm going to show you under the skirt. The below screen shot shows my last few X payouts. Full transparency.” (Hat tip to Laura Rosen Cohen at Steyn Online)

- Review: Ogilvy on Advertising: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- David Ogilvy does a masterful job of describing how to create good advertising, using anecdotes from his long career in the field.

- Where’s the Beef 40th Anniversary

- “It’s been 40 years since our iconic Where’s the Beef commercial.”

More social media

- Italian road safety campaign social media backfire

- In a perfect universe, defensive driving would be unnecessary. Too much on social media, any good idea for saving lives is denigrated because it helps people rather than laying blame.

More Twitter

- No more Twitter on masthead

- Yes, my Twitter feed is off of the masthead, due to the lack of an easy RSS feed.