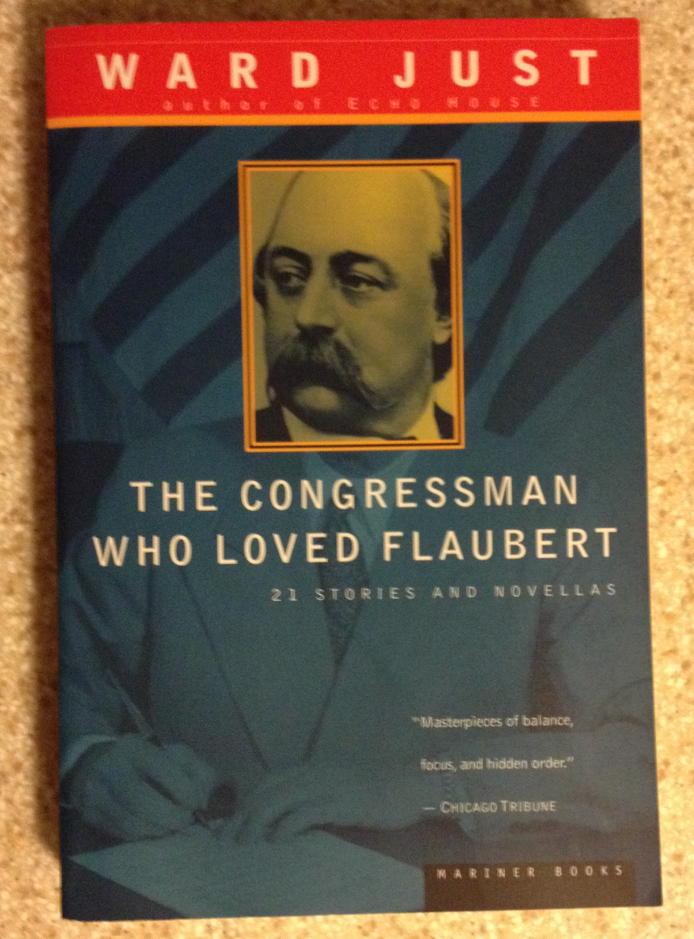

Mimsy Review: The Congressman Who Loved Flaubert

This was the year the summer would not end in Europe. Even the terrorists went about their work in short-sleeved shirts and sandals, hurtling from target to target in air-conditioned BMWs.

Around the net

Sad, autumnal reminiscences of power.

| Recommendation | Recommended• |

|---|---|

| Author | Ward Just |

| Year | 1990 |

| Length | 400 pages |

| Book Rating | 7 |

I’ve had this book on my want list for so long I can’t remember where I heard about it. I finally found it at Lamplight Books in Seattle, and from there it went into my to-read pile for five months.

I pulled it off the pile two weeks ago because I just finished the first draft of my own novel about Washington, DC, so I’m looking at how other authors have handled the town and the political class that inhabits it.

I was immediately drawn in to Ward Just’s• semifictional strata. These are some of the most depressing stories I have read in a long time. They are stories of old hands moving in and out of power, provincial progressives never quite accepted by the political class, always looking at power from the margins.

Other descriptions I’ve read say that it’s about the quest for political power, but that’s not quite right. Most of these people have either already quested for it and succeeded, or have quested and failed. In either case, they’re now on the other side of the hill, the downward slide. Superficially, they don’t think they deserve it, deep inside they know they do. It’s a lot like Chris Ware’s Acme Novelty Library for the DC class.

If there is any common theme in these stories, it is about the addictive draw—and futility—of maintenance. That is, in fact, the title of one of the stories.

He was obsessed by the weather in Vermont, being a connoisseur of bad news.

Then there’s the story of a man who befriends a local celebrity—a local Vermont weatherman—shooting up the heroin of the closeness to power T.H. White spoke of—all the while the weatherman himself is about to lose his job to a younger, prettier, more vacuous member of the new generation. She doesn’t even know how to convert between Fahrenheit and Celsius! She cares nothing for our Canadian friends across the border!

These are statesmen who don’t trust each other, for whom talking is the same as acting, who deceive their wives as blandly as they deceive the public or the enemy. And often as successfully.

The human voice travels at 740 miles an hour and listening to them in the evenings was to gain a fresh perspective on the science of ballistics.

Honestly, it’s a work I’d love to not love, these are people I’d really rather not care about. But the writing is phenomenal, and it makes it all worthwhile. If you’re looking for beautiful, stylish prose to wind out your autumn reading with sadness, I doubt you’ll go wrong to add Ward Just• to your library.

- November 17, 2015: Echo House

-

I was worried, in the first few chapters, that Echo House• would not live up to my expectations after reading The Congressman Who Loved Flaubert. It does. This is, in fact, very much a novel-length story from that collection, populated by the kind of people who can say, with a straight face, things like:

“If only the American people were as good and competent and compassionate as their government.”

This is a story of the political elite, the very elite, one of the men behind the stage pulling strings. His very name—Axel—says that he is one of the men other men pivot around. Like most of Ward Just’s• short stories from Flaubert, however, it is also filled with sadness.

In fact, if someone were to describe the book to me, I would not expect to enjoy reading it. But I did: Just is a very good writer, the rare writer who can make sad Stranger-like protagonists interesting to read about.

Washington is a town of secrets, favors, and people who know where the favors are buried.

“You’re a lucky man, to know people who repay their debts.”

And he takes his characters seriously. When he writes about the dangers of communism, the insidious spread of Soviet hegemony and the leaking of freedom from the world, the perspective he writes from is one that believes it. Yet when a Pole warns a practical man that their estimates of Soviet oppression and mass murder is low by a factor of four, and the hearer disbelieves it, attributes paranoia and irrationality to the man, Just does not let his 1996-era knowledge that the Pole is right color his treatment of the practical man’s perspective.

The bulk of the story is about the people, however, not about the politics; the politics—the lead character is, as far as I can read between the lines, part of the initial group that started the OSS and continued it as the CIA—is there only as a backdrop to the semi-generational story. The book starts with Axel Behl’s father, and ends with his son, all living at Echo House. From some perspectives Axel is the main character; from others, his son Alec is the main character; the sense of Alex as a person is often filtered through Alec’s view of the man.

There are crises, but they’re all in the background, moving from decade to decade, generation to generation. It’s a great story, and beautiful to read.

If you enjoyed The Congressman Who Loved Flaubert…

For more about politics, you might also be interested in Catch-22 government, For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko, and Boss.

For more about Ward Just, you might also be interested in Echo House.

- The Congressman Who Loved Flaubert•: Ward Just (paperback)

- These stories are a wistful look at the wrong turns and lost opportunities of the people who are not the cultural elite but would like to think they have inhabited that realm now or in the past.