Satire in the vineyard: The parable of Lolita and the sheep

This encounter does not end well for the lamb.

The morning gospel, as I write this, was the parable of the good landlord—the vineyard keeper who hired men in the morning, and then again in the afternoon, and again in the evening, and paid everyone a full day’s wages. This got me thinking about the New Testament’s “opposite parables” where Jesus tells stories that were obviously wrong to the people of the time in order to make a point about how different the kingdom of God is.

At the risk of calling ever more literary types satirical, Jesus uses a technique very similar to satire: taking an absurd situation and using it to tell a story about truth. The lessons of Jesus’s parables are a lot like the lessons of good satire: they progressed slowly into greater and greater absurdity to make a point about a truth that transcends the superficial story told.

On the surface, the parable of the workers is not clearly an opposite parable. Superficially there might be reasons why it was important to get the harvest in before nightfall. Maybe there was a storm coming, for example, and what didn’t get harvested tonight would be destroyed. But that doesn’t really make sense. Even with a storm coming, the harvest that a worker can bring in with one hour’s work needs to be worth far more than a full day’s wages for the parable to make sense in the real world that Jesus’s listeners inhabited. If it is, then the landlord is vastly underpaying his workers, and the next day they’re going to work for a different landlord who pays them up to twelve times as much.

But the most obvious way in which this is an opposite parable is that the landlord isn’t going to get any full-day workers next time. Who is going to work a full day when they can wait until evening, work one hour, and get paid the same amount? The people listening to the parable knew this. They knew how unappealing it was to do hard outdoor work throughout the day in the area around Israel. Which means that Jesus had something to say about the workers and/or the harvest that went opposite to the way the real world works. The harvest is worth more than money, or the workers are bringing in more than grapes. Or there is no day after.

Which is almost certainly the point of the parable. The harvest of Heaven is a vineyard that does not operate by the rules of this world. Not by any earthly wealth can the redemption of souls be measured, nor is the work of a single day comparable to the work of a lifetime.

Jesus’s “single day” was a metaphor not just for one man’s life, but for the life of the world. There is a storm coming, and the harvest is worth the extra effort it requires to bring in before the storm breaks.

I’m reminded, oddly, of one of the greatest writers in the English language, Vladimir Nabokov, and Lolita•. It’s very easy to get caught up in a great story and forget that it’s an opposite story. Many satirical stories take advantage of that. Nabokov is so good at it that two generations of filmmakers have taken the story as straight truth from Humbert Humbert’s pen.

In Nabokov’s novel, Humbert is a predatory liar, perhaps even a self-deceptive liar. Neither the characters in the novel nor us as readers can trust what he says. Nothing he says can be trusted. Not about how seductive Lolita• was, not about how Lolita’s mother died, not about their first encounter. Nothing is trustworthy that comes from Humbert. When he’s not lying to us, he’s lying to himself or to the people he encounters.

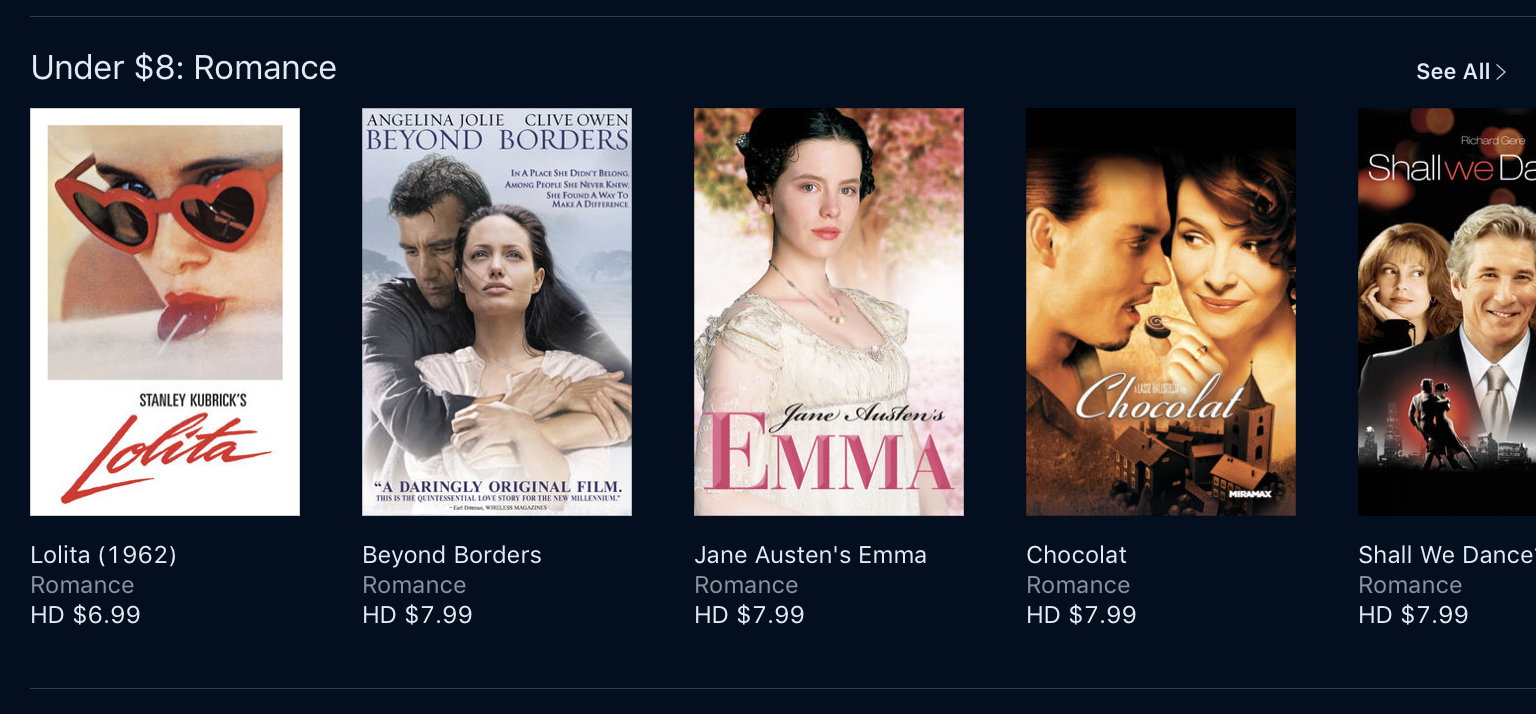

There are clues in the text that hint that Lolita was far from the Hollywood vixen she’s been portrayed as. Lolita is 12 years old when Humbert meets her. The story of Lolita and Humbert is not in any sense a romantic one. And yet Nabokov’s writing is so compelling the movie versions are repeatedly miscategorized as a romance in movie stores such as Apple’s iTunes.

One of these movies is not like the others…

Too little is said about why Humbert is untrustworthy, and why this was important to Nabokov. Nabokov had escaped two regimes notable for their untrustworthy media. He had seen how difficult it is to distrust authority when authority controls the media. Nabokov was giving us an opposite story to make a point. Nearly everything in the story was obviously false. Yet, because of its form, it becomes believable. Just as what appears in newspapers and on television is obviously false, and yet far too easily believed. Nabokov was making a point about the not yet named Gell-Mann Amnesia syndrome.

The most blatant of Jesus’s opposite parables is the parable of the good shepherd. Jesus specifically describes a “good” shepherd as one who will abandon his flock in the wilderness when one sheep goes missing.

To Jesus’s listeners, who knew shepherding intimately at first or second hand, this was clearly wrong. No good shepherd would risk their entire herd to rescue a single sheep. Some attrition was assumed: the lion and the wolf can be avoided only so long; eventually, the wolf will win. Success is measured by how few sheep the wolf takes, not by keeping the wolf at bay completely. A good shepherd would protect the whole flock, not abandon it to predation in order to find a sheep that was probably already dead and half-eaten. Unprotected sheep are easy prey for wolves, leopards, and lions.

The tale is so unsettling to modern interpreters that some people, trying to explain what Jesus meant, discard the terms “wilderness” or “open fields” in favor of assuming the good shepherd was leaving his flock in the equivalent of a modern barnyard. This guts the story. When you discard the hard parts of satire, you discard their entire purpose—like categorizing Lolita as romance. Jesus said that the shepherd left the flock in a dangerous area for a reason.

I’ve also heard the story analogized to a mother with a lost child. Will the mother not focus everything on finding her lost child? Of course she will. But she will not leave her other children in the wilderness, nor, in more modern terms, abandon them in a crowded city. She will leave them in the care of an uncle, husband, or older child—in fact, in my limited experience, if other adults are available the mother will stay with the remaining children while the husband and uncles do the searching. The mother will shepherd the remaining children to a safe place before joining the search herself.

As in the harvesting of the vineyard, there is either something special about the flock, something special about the missing sheep, or something special about the shepherd. Or all three. Every life is worth the saving; the flock is never unprotected; and the shepherd does not accept the compromises that the world demands.

The flock, like the harvest, is worth more than sheep or grapes. He values the harvest and the flock in ways that the worldly will not understand. We should not despair: sin is not the end. Unlike the sheep preyed on by wolves, when the devil culls us from the flock and feeds on us, we can still be saved. And we are worth the saving.

The parable of the lost sheep is just as well the parable of the flock left behind. Through it, Jesus is teaching us to accept the Holy Spirit. He is not leaving us unprotected. He sends the Holy Spirit for just this purpose, to always be with us and to guide us. In Matthew 10:16, Jesus said “behold, I am sending you like sheep in the midst of wolves” and then goes on to say “do not worry about how you are to speak or what you are to say. You will be given at that moment what you are to say.”

Too little is said about the wilderness in Jesus’s parable. Too little is said about the flock. And too little about why Jesus would abandon the flock to seek out the lost sheep. He is leaving us in the wilderness, but he is not leaving us alone.

In response to Satire isn’t comedy: Satire isn’t comedy. It can be, and often is, but that isn’t what makes it satire.

- Lolita•

- A brilliant novel about perception, deception, and despotism set around a European scholar’s lust for a twelve-year-old girl.

- The Parable of the Lost Sheep

- “What man of you, having an hundred sheep, if he lose one of them, doth not leave the ninety and nine in the wilderness, and go after that which is lost, until he find it?”

- The Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard

- “For the kingdom of heaven is like a landowner who went out early in the morning to hire workers for his vineyard. He agreed to pay them a denarius for the day and sent them into his vineyard.”

More Bible

- How un-Christian is the prosperity gospel?

- While I find the prosperity gospel of people like Joel Osteen weird, and am vaguely uncomfortable with it, it does contain an important teaching about God that we often forget: God answers prayers.

More Gell-Mann Amnesia effect

- Mitt Romney Day 2021: The West Side Left

- Coronavirus Calvinball? Only some black lives matter? Riots are protests and protests are riots? Who shall win the coveted Mitt Romney Day Award for 2021?

More Lolita

- Satire isn’t comedy

- Satire isn’t comedy. It can be, and often is, but that isn’t what makes it satire.

More satire

- The Walkerville Weekly Reader

- In the end times, one newspaper dared to call God to task for His hypocrisy. That newspaper was not us, we swear it. Not the eternal flames!

- Florence Foster Jenkins is Hillary Clinton

- There are too many coincidences to avoid the conclusion that Florence Foster Jenkins, the movie, is a satirical attack on the relationship between Hillary Rodham Clinton and her sexless partnership with the press.

- The definitional war on satire

- What is satire if it isn’t about current, hotly-debated events and puncturing overblown narratives?

- DriveThruRPG: satire not appropriate for current events?

- DriveThruRPG has justified their action against the Gamergate satirical card game with a very strange take on the uses of satire.

- Gamergate spreads to tabletop gaming?

- Gamergate has spread to DriveThruRPG, as OneBookShelf takes down the GamerGate card game after complaints by Evil Hat Productions.

- 25 more pages with the topic satire, and other related pages