Hot ovens: Bakers were once the slaves of time

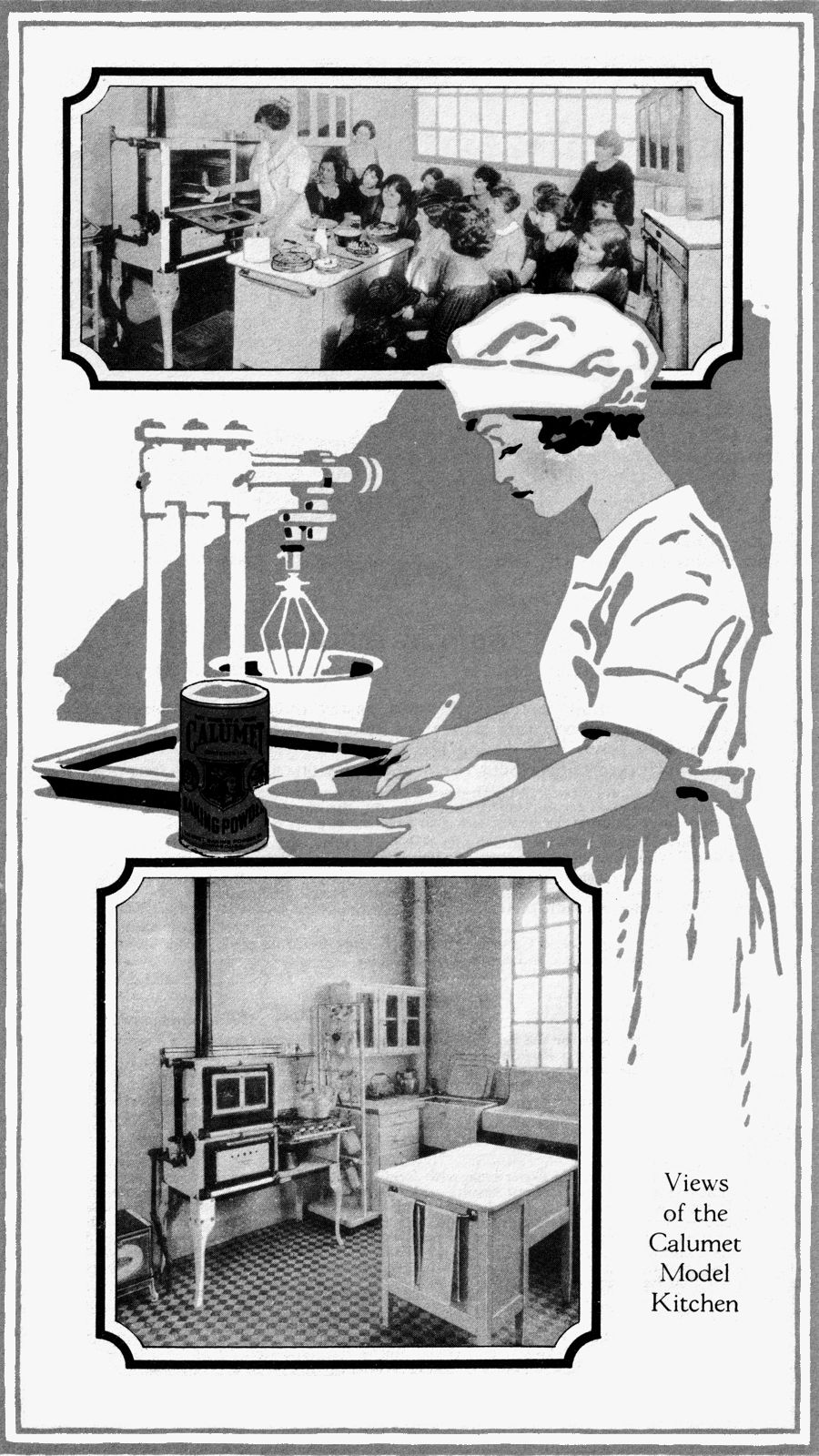

There are no set-and-forget dials and buttons on this state-of-the-art oven advertised in a 1916 Columbus, North Dakota, community cookbook.

I had an interesting sense of déjà vu watching Glen Powell of Glen and Friends use a 1914/1915 cake recipe recently. In my post about quiet ovens I wrote

The ability to trust a steady temperature in an oven isn’t just an improvement. It’s a paradigm shift. Their oven preparation process, and the terminology they used to describe it, was built around a process that simply doesn’t exist in modern kitchens.

Glen had trouble with a pre-self-regulating oven cake recipe in part because he treated his oven as a set-and-forget appliance—which, being a modern oven, it was—rather than a tool in a process, as the recipe assumed.

We have chained time in our kitchens. We have halted the decay of highly perishable foods and we have lashed baking to a schedule. We don’t have to worry about hot ovens and slack ovens and quick ovens and quiet ovens. We can literally set a temperature and a time and go do something else. And we increasingly forget that time once ruled us instead of us ruling time.

We can barely imagine the technology that inspired those old oven terms. So we make little charts corresponding oven terms to temperatures and shove our cakes into the darkness hoping for a correspondence.

Used as a rule of thumb, these charts make it possible to experiment with recipes from before modern kitchens. But when we forget that they are a rule of thumb, they instead make it more difficult to make recipes from books before the modern home refrigerator and oven. Glen’s burnt cake was a matter of running into this problem from multiple directions.

Glen recognizes that all those oven descriptor to temperature charts are inaccurate. In his 160-year-old Victorian pudding video, he said:

If you go to certain websites, if you go to Wikipedia, there’ll be a chart that tells you what a quick oven is, and that’s kind of the 2026 interpretation. In reality… this book doesn’t give a chart. A lot of them do, and when you look at the charts in the books from the time period, in that transitionary time period between ovens that had no temperature control to ovens that did have temperature control, the charts are often at odds with each other of what is a quick oven, what’s a fast oven, a hot oven, a slow oven, a medium oven.

There are, however, times he doesn’t seem to recognize why they’re inaccurate, that they reflect a process that is entirely alien to us today. Because of that, in this vintage cake-making attempt he assumed that setting the temperature to a “low end” from the charts1 and then coming in a little early to check would be all he needed to do.

The thing is, the reason those charts are inaccurate is because they are an attempt to describe a thing that is not a temperature as if it were a temperature. This isn’t necessarily obvious in the case of terms like a “hot” oven or a “cold” oven or even a “moderate” oven. But what temperature does a “quick” oven describe? What temperature does a “quiet” or a “slack” oven describe? These are not descriptions of a steady state. They are descriptions of movement toward an end.

Modern ovens use a steady supply of power combined with a thermostat to maintain a steady temperature. Old ovens did not have a steady supply of power. Nor did they have a thermostat. They were steady neither in fuel nor in fire. This terminology never described a temperature. It described a process. At best, it was a measurable starting point in a process, but it was still a process, not a steady state. Our modern ovens are not just incredibly advanced compared to the ovens used when those terms were coined, they are incredibly different.

In many ways our ovens are more understandable to someone from the nineteenth century than their ovens are to us. In my take on what is a quiet oven, I quoted the 1876 Centennial Buckeye Cook Book:

Many test their ovens in this way: if the hand can be held in from twenty to thirty-five seconds (or while counting twenty or thirty-five) it is a quick oven, from thirty-five to forty-five seconds is “moderate,” and from forty-five to sixty seconds is “slow;” thirty-five seconds is a good oven for large fruit cakes. All systematic housekeepers will hail the day when some enterprising Yankee or Buckeye girl shall invent a stove or range with a thermometer attached to the oven, so that the heat may be regulated accurately and intelligently.

That invention wouldn’t, apparently, come into general production until the twentieth century. Information is difficult to find, but it appears that, for example, the American Stove Company marketed their first self-regulating oven in 1915. This appears to be about the time that other companies introduced self-regulating ovens as well. It would take a good decade for them to become common in home kitchens.

“Milk and cream delivered daily” from the farm, in the same cookbook as the stove ad; there are no refrigerator ads in this 1916 cookbook.

The earliest self-regulating oven manuals represented on Michigan State’s Little Cookbooks site are from 1925 and 1926. In my own cookbooks, it’s at 1925 that I start to see parenthetical temperatures along with the terms (though that particular cookbook has no “hot oven”, only “moderately hot oven”).

| Cookbook | Author | Year | Hot | Very Hot | Moderately Hot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foods from Sunny Lands | Hills Brothers | 1925 | 375°-400° | ||

| Calumet Cook Book | Calumet Baking Powder | 1926 | 400°-450°, 350°-425° | 450° | 350°-400° |

| Best Chocolate and Cocoa Recipes | Walter Bake & Company | 1931 | 400°, 450°. | ||

| F.W. McNess’ Cook Book | F.W. McNess | 1935 | 400°, 500° | ||

| Brazil Nut Recipes | Brazil Nut Association | 1939 | 400°, 425°, 450° | 450° | 400° |

| Romantic Recipes | Imperial Sugar Company | 1950 | 400°, 450° | 375° |

The F.W. McNess’ Cook Book of 1935 has a very interesting outlier: one of the two “hot oven” mentions puts it at 500°. That’s for a pumpkin pie and it is at that temperature only for ten minutes. After that, the pie should be finished in a slow oven of unspecified temperature.2 Similarly, the Imperial Sugar Company’s Romantic Recipes has a pie to be baked in a hot oven at 450°, but again the heat is reduced to 400° after ten minutes.

This highlights one of the big differences between modern ovens and the older ovens these charts refer to. Until the self-regulating oven, it was up to the baker to regulate the oven. The baker had to adjust the flow of fuel, perhaps even turning it off. In fact, reading that quote from the Centennial Buckeye Cook Book again for this post, I noticed something I didn’t notice before: the author wasn’t even asking for a thermostat. All they were asking for was a thermometer so that the home baker, not the machine, could “accurately and intelligently” regulate their oven. Baking would still require constant attention or a slow cooling.

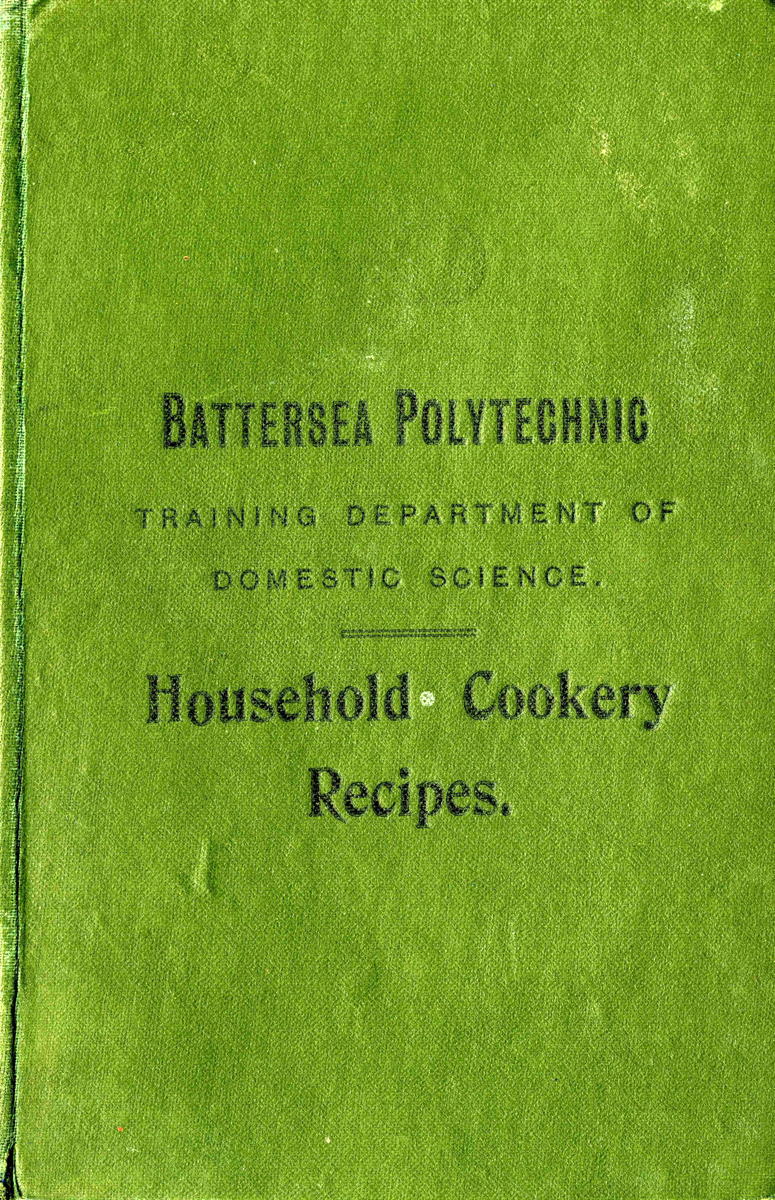

The Battersea Household Cookery Recipes cookbook was first published in 1914, in London; Glen’s copy is the second printing from 1915. If my research is right3, that would have been just before, or contemporaneous with, the first self-regulating ovens entering the home kitchen market. And well before self-regulating ovens became common in home kitchens.

The recipe Glen was trying to follow called for a hot oven and a baking time of one and a half to two hours. He set the oven to 425° and left the room. When he returned to check on the cake after only 45 minutes, it was burned black top and bottom. This was not the minor variation in oven temperatures we might expect today. The cake was a charred brick despite only being in the oven for half the minimum time specified in the recipe.

Later in the video, Glen makes the supposition that the recipe was made for someone who stayed in the kitchen, or at least near the kitchen. They would then, he suggests, have been able to smell that the cake was done in thirty minutes instead of an hour and thirty minutes. This is almost certainly true. It does not explain the estimated time being so far off.

The wider, deeper truth is that the recipe was made for someone who stayed in the kitchen because they had to. Their technology was not something that could be left alone. Even ignoring the danger of fire spreading from the oven to the house, their ovens needed constant monitoring because using their ovens was a process. Their ovens did not feature the set-and-forget buttons and dials of our modern ovens.

If you think of your oven as a process you won’t walk away. It would be like a potter walking away from the potter’s wheel. Bakers had to constantly adjust the oven’s fuel, unless they were allowing the oven to cool. And even when letting an oven cool, the baker remained to add different things to the oven at different times in the cooling process.

It’s entirely possible that the hour-and-a-half baking time is because the baker was expected to bring the oven to hot and then let it cool. As noted above, there’s a remnant of this in our modern recipes for pies; we often put a pie in at a temperature above 400°, and then quickly turn the temperature down to a temperature below 400°.4

Could that be what was going on here? The oven starts hot, and then over the next hour or two cools off? I don’t know. We really have lost a lot of understanding about how people baked before modern appliances. They didn’t have appliances, things designed to handle a task automatically. They had tools, things designed to help a human perform that task.

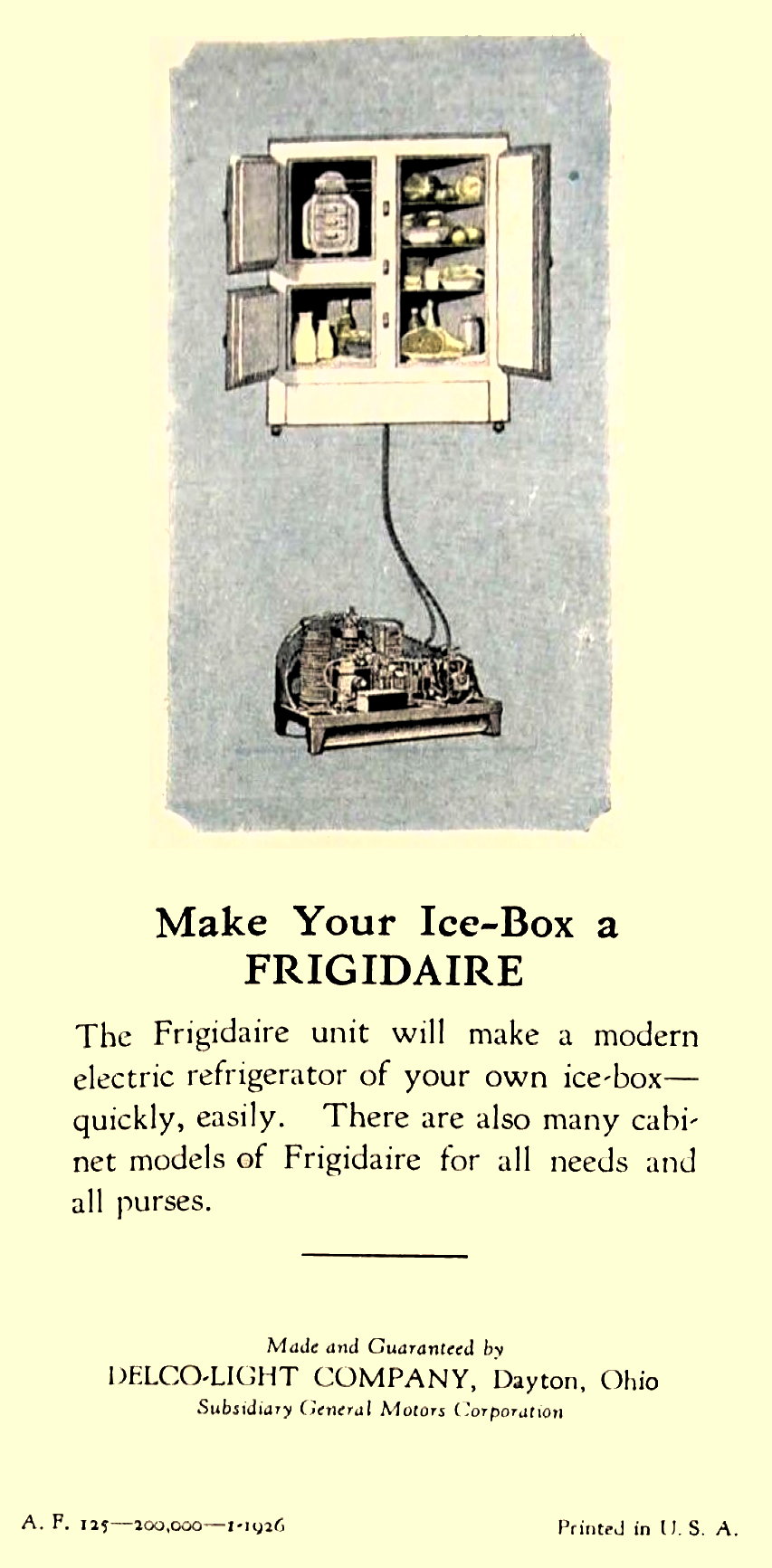

A refrigerator before 1926, if you even had one, was basically an icebox with an air-conditioner attached.

There’s a very similar recipe to Glen’s 1914/1915 Battersea recipe in May Byron’s 1914/1915 Pot-luck; or The British home cookery book:

740. AUNT-MARY CAKE (Ireland)

One and a half pounds of flour, half a pound of butter, one and a half pounds of sultanas, one and a half pounds of currants, one dessertspoonful of bread-soda (bi-carbonate ?), one pint of sour milk. Rub butter thoroughly into flour and mix all the dry ingredients, putting the bread-soda in last and mixing it well in. Last of all, put the milk. Mix all well, and bake in a greased tin for two and a half to three hours, in a hot oven to start with. When the cake has risen, the heat should be less.

I found this recipe, incidentally, by going over all of the old cookbooks I used when writing Quiet Ovens. I searched for the phrase “hot oven”. This was neither difficult nor time consuming because “hot oven” does not appear to have been a common term. Some of the hits I found weren’t even a term. The only mention of “hot oven” in Mrs. Black’s Household Cookery, for example, is that “solid cakes require a rather hot oven”. Even for the standards of the time this is less a specific description than just a recommendation that the oven, you know, should be hot.

The Aunt-Mary Cake is a different recipe than the Battersea recipe. It lacks eggs, for example, which in my very limited experience can make a big difference in cooking time. It uses nearly twice as much dried fruit. But it also shares several features with the Battersea “Housekeeper’s Cake”. It mixes the butter with the flour instead of with the sugar, what Glen calls “reverse creaming”. It calls for baking soda with no cream of tartar. And it calls for a hot oven with a multi-hour baking time. It specifies even more time than Glen’s recipe, but then, Glen’s Battersea Housekeeper’s Cake is about a third the size of the Aunt-Mary Cake: a half pound of flour instead of a pound and a half of flour, and a half pound of dried fruit instead of three pounds of dried fruit.

The really interesting parts are where the older instructions are expanded. The Aunt-Mary Cake hot oven is “a hot oven to start with”. The temperature is explicitly reduced later—and in a weirdly passive way, merely saying that “the heat should be less”.

There’s also a difference in how the milk is described, which leads to the other difference between 1915 and now.

There’s a point in Glen’s video where he ponders what the baking soda is for. After all, there’s no acid in the recipe. There is, however, milk in the recipe. Someone pointed this out in the YouTube comments, and his response was:

While yes there are acids in milk—milk will not activate/react with baking soda. Go into your kitchen, put some soda in a glass and pour in some milk. Nothing happens.

Emphasis mine. He’s leaving something very much unsaid in that description, which is that when you go into your kitchen to get a glass of milk to test this theory, you will first open your refrigerator and take pasteurized milk out. That’s why there’s practically no useful acid in it. Modern refrigerated milk can be several days old and still fresh.5

Not only is our refrigeration better, but our milk started its commercial life pasteurized. Pasteurization doesn’t appear to have become universal, in the United States at least, until 1947 on a statewide basis, and 1973 on a national basis.

Glen’s recipe is a “Housekeeper’s Cake” in a 1914 cookbook. The first modern home refrigerator was the General Electric Monitor Top in 1927. In 1915, there would have been more acid in the milk. In my opinion they would very likely have used yesterday’s milk, or the day before’s depending on whether they had an icebox and what kind if they did. But regardless of how fresh the milk is, it was not taken from what we would consider to be a home kitchen refrigerator. It started its life unpasteurized, already on the inevitable road to sour.

What would happen if we combined the sparse instructions from the Battersea Polytechnic cookbook with the more detailed instructions from the May Byron cookbook?

My reasoning is this: cakes like this don’t normally take that long to cook. If you want a slow-baked cake, you need a slow oven. And though this may sound like madness, there is method in it: this is a Housekeeper’s Cake. It might very well be designed so that the housekeeper of a boarding house or other communal living environment could put the cake into the hot oven after the final dinner item was removed, and turn off all fuel sources. The cake will be ready an hour and a half to two hours later after the table has been set, the diners have sat down and eaten, people have talked, and it’s time for a simple dessert.

In other words, this cake might specifically be designed so that the baker doesn’t have to remain in the kitchen and keep an eye on the oven.

Raisins are often soaked ahead of time in the era, so often that I suspect the technique often goes without saying. Before refrigeration, drying fruit was one means of preserving it, and soaking dried fruit was how it was reconstituted. Eating raisins raw was, I suspect, a little like eating sugar from the jar. I like whiskey-soaked raisins. So I’m soaking the raisins in whiskey. A “housekeeper” might very well soak them in hot water or even cold water.

And since it’s a one-third recipe, I’m going with two-thirds of a cup of milk (one third of a pint), somewhat sour, minus about one egg’s worth of liquid. The amount of milk in the Battersea recipe isn’t specified, only “a little bit” and a texture of “rather stiff”. Glen has a great joke about this around 06:30 in the video.

How much is a little bit of milk? This is pre-metric. English cookbook. So obviously an imperial little bit.

I’m translating “rather stiff” as “not quite stiff”. My version turned out basically cookie dough consistency. A stiff dough would just be described as stiff, not rather stiff.6 So I’m going with “still very pliable”. Your mileage may vary.

For all of these interpretations, your mileage may vary.

The other changes are “what do I have in my kitchen” changes. The substitution of candied pineapple for candied orange peel, or raisins and dried cranberries for raisins and sultana raisins shouldn’t make much of a difference, other than making a cake I like better.

Aunt Battersea’s Leave It Be Cake

Servings: 16

Preparation Time: 2 hours, 30 minutes

Baking A Vintage Cake: Fire, Failure & Redemption (Glen & Friends Cooking)

Pot-Luck or The British Home Cookery Book (ebook, Internet Archive)

Ingredients

- 4 oz raisins

- 4 oz dried cranberries

- ½ cup bourbon

- 8 oz flour

- 1 tsp baking soda

- ½ tsp cinnamon

- 3 oz butter

- 4 oz sugar

- 1 oz candied pineapple

- 1 egg

- milk (to ⅔ cup)

- sugar for sprinkling

Steps

- Soak the raisins and cranberries in bourbon for at least an hour and up to overnight.

- Preheat oven to 425°.

- Line an 8x8 cake pan with buttered parchment paper.

- Sift the flour, baking soda, and cinnamon together.

- Mix in the butter “until like breadcrumbs”.

- Mix in the sugar.

- Mix in the raisins, cranberries, and candied pineapple.

- Beat egg in a measuring cup.

- Add enough milk to make ⅔ cup liquid.

- Mix egg and milk into flour.

- Pat mixture into prepared cake pan.

- Sprinkle sugar over top.

- Bake in preheated oven until cake just starts to rise, about three to five minutes.

- Turn oven off. Bake another hour and a half or so, removing from oven when needed.

- Serve warm.

I put an oven thermometer at the front of the oven; it dropped to about 300° very quickly. An hour into the baking time it was still about 250°, and by the end it was 150°. It could very well have been left in the oven at that point until needed. If your oven doesn’t lose heat as quickly—say, if you’re using a 1915 Monarch Range made of heavy iron—you may want to turn it off immediately on putting the cake in rather than waiting a few minutes. I also suspect that the cake is at least a little forgiving regarding the initial temperature.

Now, if this is the correct interpretation—and it certainly made a wonderful spice cake—should it have been written differently in the cookbook? Yes. From our perspective it should have, and I find it hard to believe from those instructions that the Battersea Polytechnic meant to start with a hot oven and then turn it off while baking. But ovens then were so different from ovens now that I can’t be certain, especially in an instructional book that might assume there’s an instructor explaining things.7

Despite its apparent popularity I was unable to find an online scan of the Battersea Polytechnic cookbook.

Circa 1926, this Calumet Model Kitchen contains what we would call a very primitive oven. I don’t think it contains a refrigerator at all; there may be an icebox to the far right, but it’s probably just a cabinet. Not that there was much difference before GE introduced their Monitor Top.

Baking in 1915 was a process. Much of our modern advances have been about arresting these processes, about holding back the inevitable entropy of life. Just as oven terminology wasn’t a steady state but a process, food itself wasn’t just an ingredient but a process. Milk especially was a process, something any housekeeper of the time would have recognized. We arrest the process that is milk through pasteurization and refrigeration. In 1915 they didn’t have our time-stopping appliances, and pasteurization was decades into the future.

Modern bakers have completely forgotten what life was like before modern appliances, before ubiquitous and reliable power. Even if they were using an icebox, the milk had started its life with all of its bacteria intact. And whether using an early form of pasteurization or not, it hasn’t been kept cold enough to stop it from souring anyway. When I made the suggestion that the milk you “go into your kitchen” to get should not have been in a refrigerator, Glen replied that:

If the recipe writer wanted ‘sour milk’, then the recipe would/should have asked for sour milk. It didn’t.

In modern times, this is true.7 We have stopped time in the kitchen, and our day-old milk is still sweet. But there was no refrigerator in the target kitchen of Household Cookery Recipes. In that era, in the era before home refrigeration and pasteurization, milk was always in the process of souring. This is why recipes from the era often call for “sweet milk” in recipes where we would just call for “milk”.8

Absent modern refrigeration, the default is that milk is noticeably along the process of souring. Moderately soured milk doesn’t need to be specified, because before refrigeration, milk is always in the process of souring. It’s just a matter of how far along in that process it is.

While it’s possible that a “housekeeper” might have access to refrigeration in 1915, it would have been nothing like modern refrigerators. Even as late as 1926 a “refrigerator” was at best literally an icebox with a central compressor blowing cold air into it.9

Further, because milk is always in the process of souring, milk that we would consider “sour”, they would have considered merely “not sweet”. There would be no need to call it sour milk because it’s just milk. It will still have more acid than milk that’s spent the same amount of time under modern refrigeration.

I have a strong suspicion that people back then often made cakes and pies specifically to preserve milk that was on the edge of undrinkable.

One of the amazing things to me about early home refrigerators is how the manufacturers initially treated them as cooking appliances. You were expected to use them for cold cooking, setting the dial and leaving it just as you would an oven, but for cooking things like ice creams instead of things like cakes.

It is as if the concept of setting a dial and then leaving it was still an amazing new thing in the thirties, a marketing point that could be expected to attract customers.

We live a Jetson’s life compared to the world before modern refrigerators and self-regulating ovens. Everything for us is a pushbutton or a dial or a magic cabinet. We prepare the ingredients, put them into a magic box, push a few buttons, and let them be. We halt the natural processes of entropy and decay so that we no longer need fear the once-inevitable processes of life.10

We’ve had that ability for so long that we’ve forgotten what it means. We’ve forgotten that these processes were once so inevitable there was no need to mention them in a recipe. This is all because our ancestors did the work to create and maintain ubiquitous, reliable power. Without reliable power, we return to a world where milk was always souring, and babysitting ovens went without saying.

Electric lighting has obscured a sense of the toil needed to erase darkness. — Fr. George William Rutler (The Stories of Hymns)

In response to Quiet ovens and Australian rice shortbread: What is a quiet oven? How do we translate old recipes? Executive summary: 325°; very carefully. Plus, two Australian recipes for rice shortbread as a test of my theory.

Actually, I think 425° is right in the middle of what early cookbooks I have use for a “hot oven”. The term “hot oven” in my books during the transitional period is commonly followed by parentheticals as low as 400°, with one even down to 350°.

↑F.W. McNess’ Cook Book is interesting for another feature: many of the recipes specify temperatures; many of the recipes specify oven terms. Very few of the recipes specify both. It’s either one or the other.

↑I do not trust any of it. It’s all asides and random facts rather than contemporaneous knowledge. I recommend that you not trust what I’m writing either. I’m just some guy on a blog. I don’t have even half the cookbooks or experience Glen does.

↑I recognize that this is wildly speculative. It would be very weird for a 1914 cookbook. On the other hand, it’s not completely out in left field. If you have a hot oven and you want to cool it while a cake is baking, without a thermometer, what is the easiest way to do that without disturbing the cake? Stop adding fuel. Bank the heat from any existing fuel away from the baking area, if you oven is that advanced.

↑Glen is glossing over a whole lot in that thought experiment. Here’s another experiment: instead of using milk, use water. As with milk, “nothing happens”. Now, bring that water to a boil first, and then pour it over baking soda. A whole lot happens. Baking soda can release gas without an acid at higher temperatures… such as the temperatures in a hot oven.

↑An “iron horse” is after all “not a horse”.

↑Glen seems to assume that because this was a teaching text it would be more detailed than normal cookbooks and not leave important techniques out. My experience with instructional books of all kinds is the opposite of that: instructional books often leave out things the instructor is expected to make clear.

Glen himself comes very close to making this point in his Victorian Pudding video, but then walks it back: “So, this is a teaching text. and it says nothing about these things. This is a teaching text with some of the most basic cooking recipes you could ever imagine in it. You know, I’ve got teaching texts from the 1800s that told people how to make toast or fry an egg. And yet on the more difficult recipes, they leave parts out. And so you can’t tell me that a book that has something that’s super simple, um, a recipe for something that’s super simple just expects you to know how to do the hard stuff.”

Glen, you just told yourself that.

↑My father grew up on a farm that was late in getting home refrigeration. He remembers that his parents rented refrigeration space at the local grocery store before they bought a refrigerator. He prefers his milk to be what I consider sour, and will drink it well into when I would relegate it to the freezer for baking.

↑Glen seems to have originally thought that home refrigerators were on sale in 1915, but then changed his mind. I can see the summary of the comment, but not the comment—or even the thread—itself. It looks like the original commenter removed their comment, which, on YouTube, means the entire comment thread is gone. Since I can’t read Glen’s full comment, I can’t be sure he wasn’t making a joke starting with “they were being sold in 1914” or that he wasn’t talking about industrial refrigerators for businesses or schools. In fact, the cut-off end of YouTube’s summary suggests he may have believed that the Battersea Polytechnic would have had an industrial refrigerator. If so, I would answer that this is still a Housekeeper’s Cake, and that our interpretation of the recipe should reflect that.

↑I originally planned to post this two weeks earlier. I didn’t think it was going to be a problem testing this recipe with sour milk in time for the earlier post date, because I had a half-gallon of milk, already open, and several days past its expiration, in the fridge, on the Wednesday before the go-live Wednesday. I figured I’d be able to make the cake over the weekend.

Well, it’s Sunday afternoon as I write this after having enjoyed a bowl of granola with decidedly non-soured milk. So I had to push back the go-live date by two weeks (to skip over last week’s hard-publication date) in order to test the cake recipe.

I should have just left it out, as if I didn’t have a refrigerator at all. But I was interested in the time to begin souring in a modern kitchen.

↑

food history

- Quiet ovens and Australian rice shortbread

- What is a quiet oven? How do we translate old recipes? Executive summary: 325°; very carefully. Plus, two Australian recipes for rice shortbread as a test of my theory.

- Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Nasty, brutish, and short. Unreliable power is unreliable civilization. When advocates of unreliable energy say that Americans must learn to do without, they rarely say what we’re supposed to do without.

- Your Stove is Broken!: Owen Wyatt, Christina Chonody, and Julian Weisner

- “It feels like it must have been long ago that we were building houses around the need for a cellar to keep our food cold, or ensuring proper ventilation for the wood-burning stoves when we needed to cook food. Yet, neither the home refrigerator nor the temperature-controlled oven began making their way into American homes until the beginning of the 20th century! ”

sour grapes

- A Contrived Example of Game Play

- The Order of the Astronomers is an example of what might happen when player characters delve into the wilderness, discover lost ruins, and encounter monsters, traps, and fantastic adventure!

- Granola, the ultimate breakfast

- Granola tends to be the more expensive cereal in stores, but the easiest and cheapest to make at home.

videos

- Baking A Vintage Cake: Fire, Failure & Redemption: Glen Powell at Glen & Friends Cooking

- “After last week’s… let’s call it a learning experience, I decided this book deserved an opportunity for redemption. So today we’re making Housekeepers Cake…”

- Baking Soda and Boiling Water: Jerry Stratton at Mimsy@YouTube

- “What happens when you pour boiling water into baking soda? No acid, just water. Baking soda reacts to heat as well as to acid.”

- Glen & Friends Cooking: Glen Powell

- “We are food people… We grow our own gardens, we pickle, we make jam, we start with base ingredients… FOOD!”

- This 160-Year-Old Victorian Pudding Surprised Me | Pudding with Rough Puff Pastry: Glen Powell at Glen & Friends Cooking

- “Today we’re diving deep into a forgotten Victorian dessert: Amber Pudding, straight out of Williamson’s Cookery, 6th edition, 1864, published in Edinburgh, Scotland.”

vintage cookbooks

- The Centennial Buckeye Cook Book at Internet Archive (ebook)

- “In the effort to avoid the mistakes of others, greater errors may have been committed, but the work is submitted just as it is to the generous judgment of those who consult it, with the hope that it may lessen their perplexities, and stimulate that just pride without which work is drudgery and great excellence impossible.” Compiled by the Women of the First Congregational Church, Marysville, Ohio.

- Household Cookery and Laundry Work: Mrs. Black, F.E.I.S. at Internet Archive (ebook)

- “A great deal more of a country’s prosperity depends upon comfortable homes than philosophers might be willing to acknowledge.”

- Little Cookbooks at Michigan State University

- “The Alan and Shirley Brocker Sliker Culinary Collection… Little Cookbooks contains thousands of food and cookery related publications produced primarily by companies in the United States from the late nineteenth century up to the present.”

- Pot-Luck or The British Home Cookery Book: May Byron at Internet Archive (ebook)

- “Over a thousand recipes from old family M.S. books.”

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1927 Electric Refrigerator Menus & Recipes

- The very first modern refrigerator/freezer came with a very revelatory cookbook that treated customers nearly the same way computer manuals would exactly fifty years later: as partners in a revolutionary new means of creativity.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Review: The Best in Cooking in Westfield: Jerry Stratton

- “The title appeared to be ‘The Art of Cooking in Geneva’. But then, inside, it had three more covers: ‘Out of Springfield Kitchens’, ‘Home Cooking Secrets of Evanston’, and ‘The Best in Cooking in Westfield’.”

- A Taste of the Past

- “Battersea Polytechnic and later the University of Surrey published a cookbook, first published in 1914… it was used and relied on, not just by students but also home economics teachers throughout the country.”

More baking

- Quiet ovens and Australian rice shortbread

- What is a quiet oven? How do we translate old recipes? Executive summary: 325°; very carefully. Plus, two Australian recipes for rice shortbread as a test of my theory.

- Stoy Soy Flour: Miracle Protein for World War II

- To replace protein lost by rationing, add the concentrated protein of Stoy’s soy flour to your baked goods and other dishes!

- El Molino Best: Whole grains in 1953

- El Molino Mills of Alhambra, California, published a fascinating whole grain cookbook in 1953.

- Club recipe archive

- Every Sunday, the Padgett Sunday Supper Club features one special recipe. These are the recipes that have been featured on past Sundays.

- Three from the Baker’s Dozen

- Three recipes from a Baker’s Coconut pamphlet once included in McCall’s magazine: coconut squares, chocolate cheesecake, and broiled coconut topping.

- One more page with the topic baking, and other related pages

More food history

- Using ingredients to guess cookbook years

- Community cookbooks often call for brand name products and tools. That can provide a lower bound for what year a book was published, but rarely an upper bound.

- Using archives to guess cookbook years

- Many cookbooks, especially community cookbooks and often advertising pamphlets, leave off the year. Online newspaper and magazine archives can help to narrow down when the book was published.

- Padgett Sunday Supper Club Sestercentennial Cookery

- The Sestercentennial Cookery is a celebration of American home cooking for the 250th anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence.

- Table and Kitchen: Baking Powder Battle

- The Royal Baking Powder Co. was a very combative entrant in the baking powder wars. But that kind of competitive spirit can also mean great recipes.

- Using search engines to guess cookbook years

- Many cookbooks, especially community cookbooks and often advertising pamphlets, leave off the year. Often, however, there are solid clues in the text that narrow down when the book was published, through simple online searches.

- 28 more pages with the topic food history, and other related pages

More ovens

- Quiet ovens and Australian rice shortbread

- What is a quiet oven? How do we translate old recipes? Executive summary: 325°; very carefully. Plus, two Australian recipes for rice shortbread as a test of my theory.

More refrigerators

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1937 Kitchen-Proved

- Refrigerators started to take off during Prohibition, and became ubiquitous following World War II. This Westinghouse refrigerator manual and cookbook gives us a glimpse at home refrigerator/freezers in the Great Depression.

- Refrigerator Revolution Reprinted: 1928 Frigidaire

- If you’d like to have a printed copy of the 1928 Frigidaire Recipes, here’s how you can get one. Also, a lot of new recipes tried.

- Four New Ices and an Ice Cream Cookery

- Philadelphia Ice Cream, Walnut Nougat, Lemon Cream Sherbet, and Cranberry Ice. Four more new no-churn ice creams and desserts for Summer 2025. And, a book collecting all my favorite no-churn ice creams if you’re interested!

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1947 Cold Cookery

- The 1947 Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest reflects not just increased access to electricity but also the end of a second world war.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Three more pages with the topic refrigerators, and other related pages

Another difficulty in old recipes is how one treats a "beaten egg." My great grandmother left behind many family-favorite Christmas cookie recipes, which my late mother and aunt would dutifully execute each year. They swore that the cookies were different from that they remembered as a child. Eventually, after much trial and error, they determined that the "beaten eggs" were eggs which were separated, the yolks and whites beaten separately, and the beaten whites folded into the batter. The changes wrought by refrigeration and modern stoves and ovens are no less startling than the introduction of motive power to the process of making cookie and cake batter.

Owen Richelieu III in Milwaukee, Wisconsin at 1:43 p.m. February 20th, 2026

NMWNS

Yes! I am nearly certain that some recipes just call for “eggs” when they mean “separated eggs” because everyone knows that when you make this particular dish (a pudding, or a quick bread such as a waffle, for example) you have to separate the eggs. This is especially true when the egg white is providing leavening.

Nowadays, for me at least, it is sometimes very difficult to tell which they meant.

Jerry Stratton in Texas! at 2:53 p.m. February 20th, 2026

yFmrE