Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1937 Kitchen-Proved

Also available in print.

I’ve written so far about refrigerators in the twenties and refrigerators in the forties. While traveling over the Thanksgiving holiday last year I found an interesting Westinghouse book from 1937 or 1938. It provides a great opportunity to fill the gap and look at the thirties. If I’m right about the age, this book came out well after the end of Prohibition and well before the end of the Depression. Those who were paying attention to world affairs could see another Great War on the horizon, but for most people domestic concerns were a far greater priority.

Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Frigidaire, 1928

- Cold Cooking, 1942

- Cold Cookery, 1947

- Kitchen-Proved, 1937 ⬅︎

- General Electric, 1927

- Refrigeration, 1926

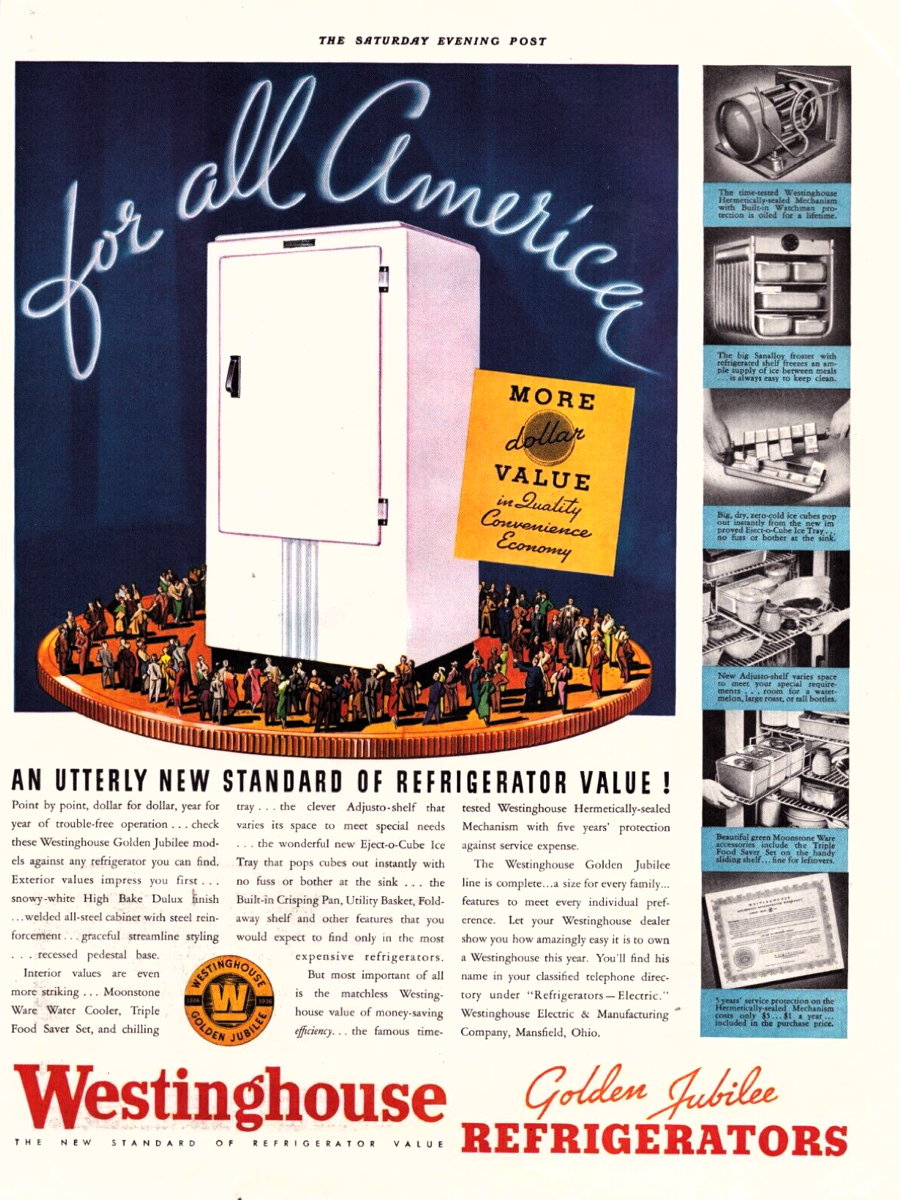

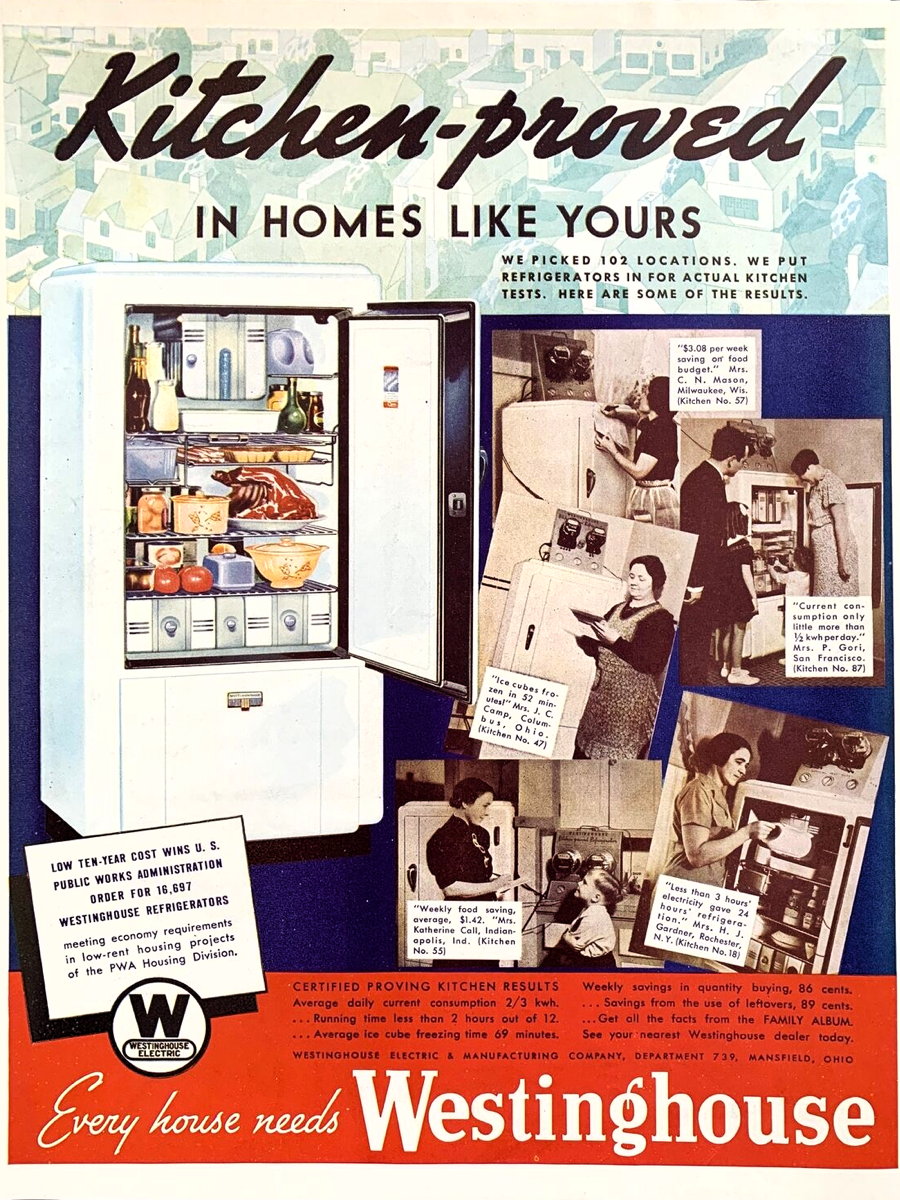

The Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved Refrigerator Book (PDF File, 11.6 MB)—also available in print—is undated but has a drawing inside that matches Westinghouse’s 1937 and early 1938 advertisements in magazines such as Good Housekeeping and The Saturday Evening Post. I suspect that the book is from 1937, because all of the ads from 1938 that feature this refrigerator and that include a month are from very early in the year.

This book is a lot lower quality than the 1928 Frigidaire Recipes. This is reflected in the quality of the paper, in the physical format—it’s a paperback instead of a hardcover—and in the graphic design. Where the older book used an elegant presentation of color illustrations and few recipes per page, Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved packs the recipes in. Text is in double columns and the only nod to color is a solid green background around chapter headings, chapter photos, and page numbers.

The photos are black-and-white and not obviously retouched. They’re also prime fodder for a James Lileks regrettable food collection. Unless there’s been some very strange color degradation since the book was published, they paired those black and white photos with off-green borders. This is not an appetizing combination. It’s as if the book was designed to directly contrast with the elegant designs of the previous decade. This is not the Roaring Twenties. This is the Depression Thirties. No elegance for you!

Despite the higher word density, the “Westinghouse advantages” are succinct, all in one paragraph, albeit a long, dense one.

The first [advantage] is ECONOMY. You will find that your Westinghouse uses very little electricity. This is due to (1) the efficiency of the unit; and (2) the insulation which protects the food compartment against outside heat. The second is completely dependable FOOD PROTECTION. Your Westinghouse has the necessary POWER to provide safe food protection temperatures even in the hottest weather. Added to this is the safeguard of the famous Built-in Watchman, an exclusive Westinghouse feature, which turns off the unit in case of unusual power line disturbances which may be caused by thunder storms, and turns it on automatically when the danger has passed. A third is CONVENIENCE. The shelves are so arranged that you can store large amounts of food and reach everything easily when needed. This means you can save on perishable foods by buying in larger quantities and on bargain days. A fourth is the FAST FREEZING of ice and desserts.

That introduction was attributed to Edna I. Sparkman, a very fitting name for a Director in the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co.

Protection against power fluctuations doesn’t appear as a feature in either of the 1920s books I have or either of the 1940s books in this series. I wonder about the technology behind the “Built-in Watchman”, but can see the need. Quickly turning on and off is bad even for modern electric appliances, but especially for ones with moving parts. Power lines then and for long after were mostly above ground and vulnerable to anything else above ground, not just to thunderstorms. High winds still cause power fluctuations today in areas where trees are prevalent near above-ground power lines. They’re vulnerable to vehicles, and even to animals. My dad lost power while I was visiting him earlier this year due to a suicidal squirrel.

From the March 14, 1936, Saturday Evening Post, this is clearly not the refrigerator pictured in Kitchen-Proved—a phrase which does not appear in this ad.

Not only does this 1937 Saturday Evening Post ad show a refrigerator like the one in the book, it’s titled “Kitchen-Proved.”

For all that economy and those benefits refrigerators in the thirties are still a lot of work. While the initial Operating Instructions say to defrost “when frost is about one-fourth inch thick”, the facing page recommends more frequent defrosting:

Weekly cleaning and defrosting are desirable, regardless of the thickness of frost.

There is also a yearly task to take care of—one that remains necessary, sort of, even for modern refrigerators.

CONDENSER Once a year, preferably before hot weather, dust should be cleaned from condensers. Open the refrigerator door, turn dial to ‘Off’ and remove the lower panel by pulling out from the bottom. Remove screws from inside panel and clean condenser.

Is “preferably before hot weather” a term for “spring cleaning”? The term “spring cleaning” has existed in the household sense since at least the 1840s. “Preferably before hot weather” seems like an odd turn of phrase, requiring a predictive capability beyond us today unless it’s meant in the seasonal sense.

My own refrigerator, probably a 2008 model, says that I only need to clean the condenser if I have pets or if I live in a particularly dusty climate. And then it should be done “every 2 to 3 months”.1

The “Economy Buying” section must have been a fascinating read even at the time.

Your Westinghouse Refrigerator is economical. Our Kitchen Proving Hostesses tell us that by buying at week-end economy prices they are able to save an average of 85 cents a week. They buy perishable vegetables when fresh and in sufficient quantity to effect savings. Buy meats as roasts rather than chops or steaks. The rate per pound is lower, there is less waste, and roasts go farther. Also buy large cans of fruits and vegetables as the price is less, and there will be no spoilage if leftovers are stored in a Westinghouse. Our hostesses tell us further that their savings on leftovers average another 85 cent saving, a total for both, of about $90 a year. Savings on food plus savings over previous refrigeration costs gave a further saving of about $20. These easy savings amount to an average of $110 a year.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation calculator, that $110 is a savings of $2,530.78 in modern money. That’s some nice savings! Likely the “previous refrigeration costs” are for ice-based refrigeration, not earlier models of electric, iceless, or automatic refrigeration. In 1937, according to the census, only 73% of dwellings—and only 18% of farms—even had electricity. This was a three-point and a four-point jump, respectively, from the year before. The potential market for new electrical devices was growing quickly.

This book has less alcohol than the prohibition-era Frigidaire Recipes. The book’s Beverages and Cocktails section only has one actual alcoholic add-in: the Reception Punch includes creme de menthe. Even the Roman Punch only has rum flavoring. And that creme de menthe might not be alcoholic: there’s a recipe for Creme De Menthe Syrup on the facing page. The only alcohol the syrup contains will be from the peppermint and mint flavorings. Flavorings were never covered under Prohibition.

The only recipes that definitely mention real alcohol are the Nesselrode Pudding variation of Rich Ice Cream, which contains sherry; the Fruit Delight variation of the Chantilly Parfait, which optionally can contain rum or sherry; and the Curry of Meat Mexican which calls for two tablespoons of sherry, again optionally.

If I’m right that this book is from 1937, prohibition had been repealed four years earlier. But something people often forget—myself included—is that the repeal of the 21st amendment did not end prohibition in the United States. Many states maintained their own prohibition laws—which predated national prohibition—for decades. Mississippi doesn’t appear to have ended full prohibition until 1966!

And of course, 1937 was also the height of the Depression: elegant cocktail parties weren’t on everyone’s mind. The Canapés and Sandwiches section has only a single page of recipes. As Frigidaire Recipes showed, some people continued holding cocktail parties even through national prohibition. This book, and so possibly this refrigerator, wasn’t marketed to such people.

Evaporated milk as a whippable replacement for heavy cream still involved scalding the milk, and, in this case, adding gelatin. The book doesn’t offer an option to merely chill the evaporated milk in the refrigerator or freezer and whip immediately. This matches the transition from scalding to freezing evaporated milk evident in the various editions of The Joy of Cooking. The new method appears to have been discovered or become possible sometime in the early forties.

The Honey Ice Cream called for both top milk and either a cup of coffee or light cream. Since I like my ice cream to be creamy, and because “top milk” is harder to come by nowadays than it was in 1937, I chose to downgrade the milk and upgrade the cream.

Honey-Coffee Ice Cream

Servings: 6

Preparation Time: 1 hour, 15 minutes

The Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved Refrigerator Book (PDF File, 11.6 MB)

Ingredients

- 1 cup milk

- 1 tbsp finely-ground coffee

- 2 eggs, separated

- ½ cup honey

- 1 cup whipping cream

- 2 tbsp sugar

- 1 tsp vanilla

Steps

- Scald the milk, with the coffee wrapped in cheesecloth.

- Let cool; squeeze the coffee to release all liquid, to the strength desired.

- Beat egg yolks until light and lemon colored.

- Gradually add honey while continuing to beat eggs.

- Add milk and cream and blend thoroughly.

- Beat egg whites until light.

- Add sugar, continuing to beat until glossy.

- Fold egg whites and vanilla into the cream.

- Freeze until half frozen, three to five hours.

- Whip or beat until smooth and bubbly.

- Pour into a chilled bowl and return to freezer.

- Freeze several hours or overnight.

As you can see, I also chose to combine the option of a cup of coffee or cream to a cup of coffee-flavored milk and cream. This turned out quite nice, without the hassle of adjusting the freezer’s Temperature Regulator.

Ice cream remained a selling point for these refrigerators, at least in the mind of the advertising departments, and part of that was making sure that people still felt that ice cream was worth the cost during the Depression. One of the more interesting economies in Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved is the difference between “Rich” ice cream and “Economy” ice cream.

| Rich Ice Cream | Economy Ice Cream |

|---|---|

| 1-⅓ cup top milk or evaporated milk | 1 cup top milk |

| 1 cup whipping cream | 1 cup light cream |

| ½ cup sugar | ¼ cup sugar and ¼ cup corn syrup |

| 2 eggs | 2 eggs |

| 1 tsp vanilla | 1 tsp vanilla |

| 1 tsp salt | about a dash in the syrup |

| 2 tbsp sugar | 2 tbsp sugar |

There’s not much difference in ingredients. Corn syrup was probably slightly cheaper than sugar; I’ve also seen this substitution in pamphlets addressing wartime restrictions. Usually corn syrup is added to make the ice cream smoother, not for economy. The only real difference is that the cream is replaced with light cream; this necessitates freezing the mixture before whipping the cream.

The two recipes also use two different styles. The Rich Ice Cream lists all of the ingredients. The Economy Ice Cream leaves minor ingredients to the description, in this case the small amount of sugar used when beating the egg whites.

The Economy Ice Cream is the only recipe with “economy” in its title.

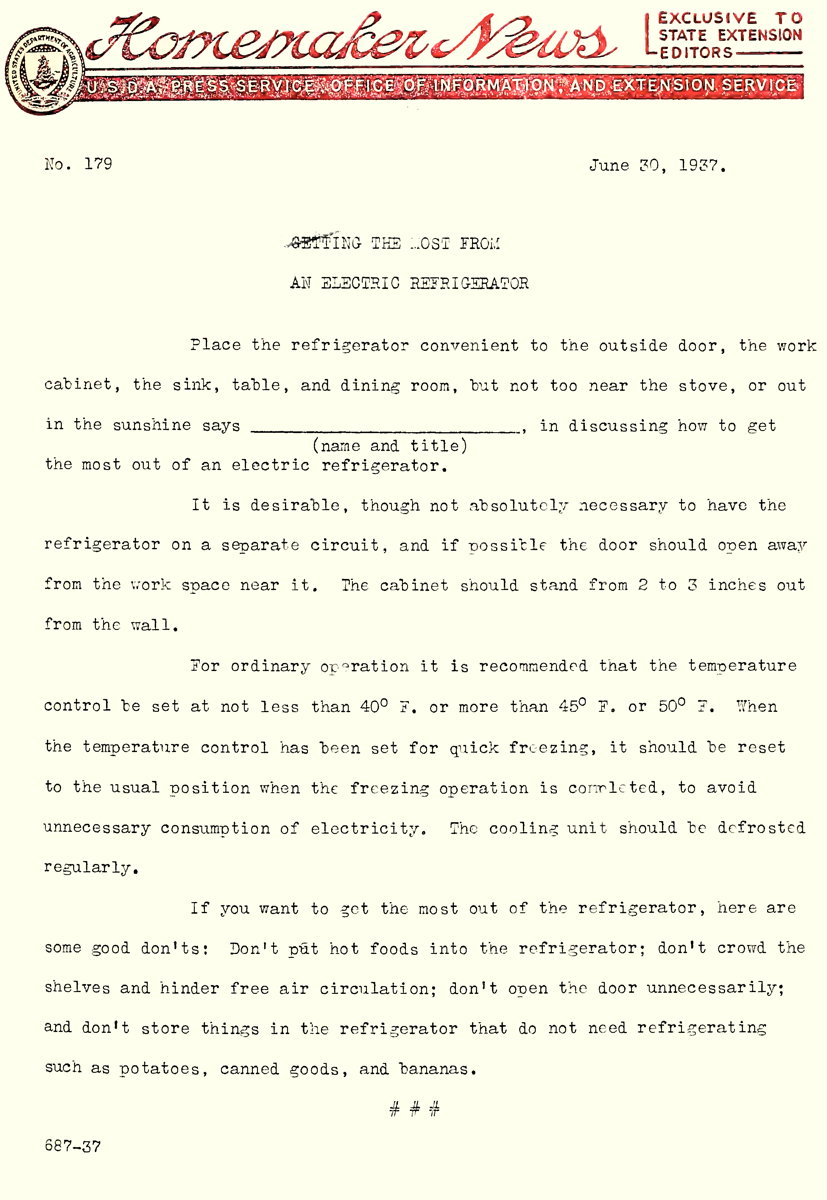

Notice that this was meant to be attributed to someone else as if they said it themselves rather than coming from the USDA!

Westinghouse may have been performing some “economies” of their own. Unlike Frigidaire Recipes there is no author listed for this book. Westinghouse didn’t pay a famous author to write their book, as earlier manufacturers did. The difference in nomenclature between recipes may come from pulling recipes from different sources and using them as-written, despite the implication in the introduction that the recipes have all been tested by Westinghouse’s “Kitchen-Proving Hostesses”. On pages 17 through 19, the “Breads and Cookies” recipes call variously for butter, shortening, butter and lard, and fat. Butter and lard, as far as I know, had their modern meanings in 1937. But shortening and fat? Did these also mean different things, or does it just reflect the terminology used by differing original sources?

That variation in terminology comes despite a growing set of standards in recipe writing:

NOTE: All of the quantities used in the recipes of this book are standard. One cup, liquid, equals ½ pound. One tablespoon is 1⁄16 of a cup. One teaspoon is ⅓ of a tablespoon. These abbreviations have been used: t. equals teaspoon. tb. equals tablespoon. pkge. equals package.

There’s also a short list converting standard can sizes to both weight and volume. More interesting is that they’re transitioning from oven descriptors to specific temperatures. Many of the temperatures are of the form “bake in a hot oven, 450° F. for…” or “bake on cooky sheet in hot oven (425° F.) for…”.

| Descriptor | Temperature | Appearances |

|---|---|---|

| Very Hot | 450° F. | 1 |

| Hot | 450° F. | 3 |

| Hot | 425° F. | 3 |

| Hot | 400° F. | 2 |

| Hot | 400° F. to 425°F. | 1 |

| Moderate | 370° F. | 1 |

| Moderate | 350° F. | 2 |

| Slow | 325° F. | 1 |

While there are no other “economy”-titled recipes in the book, there is an entire section for “Leftovers”. Like Frigidaire Recipes (1928) and unlike Montgomery Ward’s Cold Cooking (1942) this book does not rely heavily on gelatin (or aspic). Gelatin is, however, in the process of taking over.

There are seventeen recipes for reusing leftovers. Two, the Buffet Meat Loaf and the Turkey and Ham Mousse, call for gelatin, now spelled without the trailing “e”. Some recipes use “salad aspic”, available in packages. The Jellied Meat Loaf and the Jellied Fish Loaf each call for two packages of salad aspic.

The salads are where gelatin is beginning its rise to power. Twenty-one of the thirty-six recipes in the Salads section are gelatin-based. This even includes the Tomato Aspic, which calls for lemon-flavored gelatin instead of “salad aspic”. The Sioux City Fruit Salad doesn’t call for either gelatin or aspic, but it does call for melted marshmallows, which probably contained gelatin.

Whatever “salad aspic” is, it doesn’t appear in any of the salad recipes. The Royal Deviled Eggs recipe does call for “2 packages prepared aspic”, which might or might not be the same thing.

I tried two of the salads, both of which called for gelatin. For the Cottage Cheese Ring I really had no idea what to expect. That’s part of what appealed to me. It is definitely a buffet dish: the appearance was striking. Overall, it was bone-china white and the cottage cheese gave it a sort of marble or stone-like appearance. Filled, the ring would provide a remarkable contrast with the colors of the fruit or vegetables inside the ring.

The texture was creamy, which was also a nice accompaniment to the apple/grape salad I put inside the ring. It had little flavor of its own, but did combine well with the salad. It isn’t something I’m likely to make for myself again, but I might make it for a party or cocktail if I feel like showing off.

I also made the Cranberry Jelly Salad, mainly because I enjoy cranberries but also because I had for some reason a package of cherry gelatin that I would otherwise never use. It’s not likely something I’ll make again. The flavor was fine, but the texture was sparse. Like Tolkien’s “butter over too much toast” this was “cranberries over too much gelatin”. That said, I ate it as its own dish. If served with chicken salad as the recipe suggests, that texture might well have been more appropriate. And, of course, this may have been a Depression recipe, using gelatin to extend the ingredients.

Incidentally, I have a new procedure for unmolding gelatins: extreme patience. Rather than try to warm the outside with my hands or a towel or a wet washcloth, I just let it sit upside down over a plate, and in half an hour it fell out. I then put it back in the fridge (still covered by the mold) until needed.

No-Knead Clover Leaf Rolls

Servings: 18

Preparation Time: 45 minutes

The Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved Refrigerator Book (PDF File, 11.6 MB)

Ingredients

- 1 cup boiling water

- ¼ cup sugar

- ½ tbsp salt

- 1 tbsp lard

- 2 tbsp lukewarm water

- 2-¼ tsp yeast

- ½ tsp sugar

- 1 beaten egg

- 4 cups sifted flour

- melted butter

Steps

- Mix boiling water, ½ cup sugar, salt, and shortening.

- Stir yeast and ½ tsp sugar into lukewarm water.

- Stir yeast into dough.

- Mix in beaten egg.

- Stir in 2 cups flour, beating thoroughly.

- Stir in remaining flour, mixing well.

- Brush the top of dough with melted butter.

- Cover tightly and store in refrigerator until ready for use.

- For each roll, use greased fingers to make three half-ounce balls.

- Place three balls in muffin tin for each roll.

- Bake at 400° for 15-20 minutes.

Refrigerator rolls are another interesting cultural shift. This book’s recipe makes about 36 rolls. The dough is meant to be stored in the refrigerator until needed. The 1928 Frigidaire book had rudimentary refrigerator rolls: a note—in their Pastry section—that “Yeast dough may be kept covered indefinitely in Frigidaire”. But the dough itself wasn’t much different than any yeasted dough. These Westinghouse rolls are true refrigerator rolls, using a different technique for the refrigerator.

Held at the low Westinghouse Refrigerator temperatures, this dough will keep for a week or ten days.

I tested that timing over Christmas; it seems about right. My last batch was exactly two weeks after mixing the dough. They were good, but they didn’t rise as much and had the texture and flavor of English muffins. I don’t think they would have gone any longer.

As an accompaniment to the rolls I also tried the Cream Cheese and Ginger sandwich spread.

The combination of flavors in this sandwich is very unusual and appetizing.

It’s about as simple as you can get: a package of cream cheese2, two tablespoons chopped candied ginger, and enough “top milk” (I used cream) to soften the mixture for spreading. This is a wonderful flavor and does indeed create an unusual and appetizing sandwich.

Besides making a great buffet finger sandwich, it also makes a great filling for celery and apple slices. I even used it as a tortilla chip dip. The saltiness of the chips was a nice contrast to the sweetness of the ginger.

Peanut Butter Biscuits

Servings: 14

Preparation Time: 45 minutes

The Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved Refrigerator Book (PDF File, 11.6 MB)

Ingredients

- 2 cups sifted flour

- 1-½ tbsp baking powder

- 1 tsp salt

- 2 tbsp lard

- ¼ cup peanut butter

- ⅔ cup milk

Steps

- Sift flour with the baking powder and salt.

- Cut in lard and peanut butter.

- Mix milk in thoroughly.

- Roll and cut into 1-¾ inch biscuits.

- Bake for 10-12 minutes at 450°.

The Baking Powder Biscuits are also an interesting use of the refrigerator. Like the Refrigerator Rolls, the dough is meant to be stored in the refrigerator for use as needed, “for a week or more”. I’ve seen refrigerator roll recipes in relatively modern cookbooks, but make-ahead biscuit mixes usually just mix the dry ingredients, requiring that you add shortening and liquid as it’s used. These refrigerator biscuits add the shortening for storage, so that the only thing you need to add later is the liquid.

I tried the Peanut Butter Biscuits variation. They were unsurprisingly nice toasted and buttered, but were also great as the base for an applesauce shortcake. I did not try storing the dough in the refrigerator: the recipe only makes 14 biscuits, which is another interesting choice. The basic Baking Powder Biscuits recipe makes 28 biscuits. All of the specialty variations “are for half of above recipe”. This makes a lot of sense. Where basic biscuits are something you’d make over time, specialty biscuits would be made all at once for a gathering or special treat.

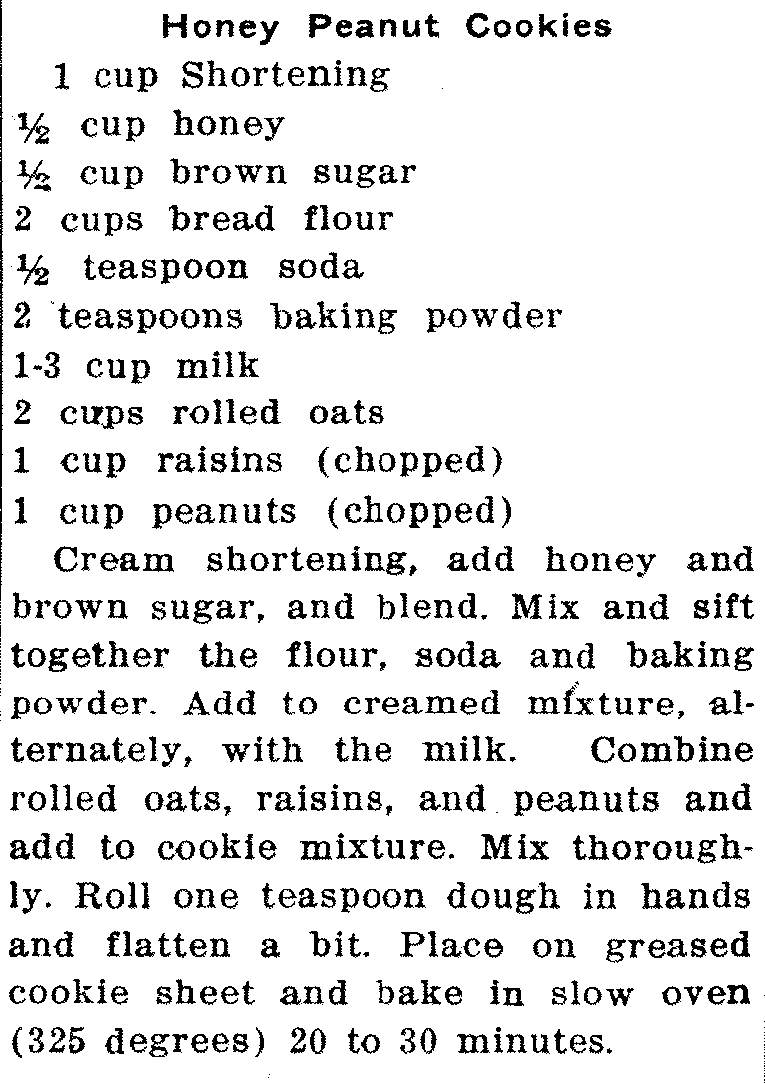

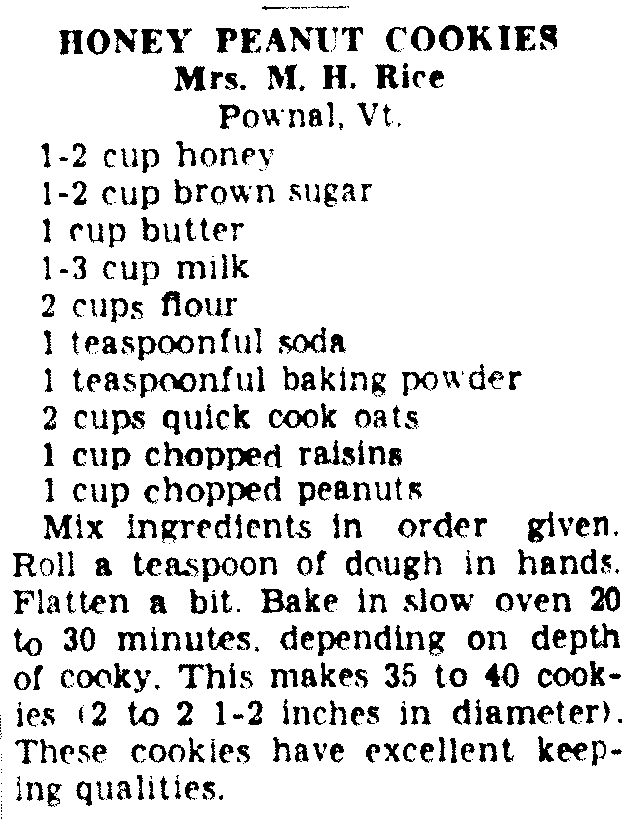

Wonderful early example of oatmeal cookies. No eggs. A little milk. I used cranberries instead of raisins, because I like them, with oatmeal especially.

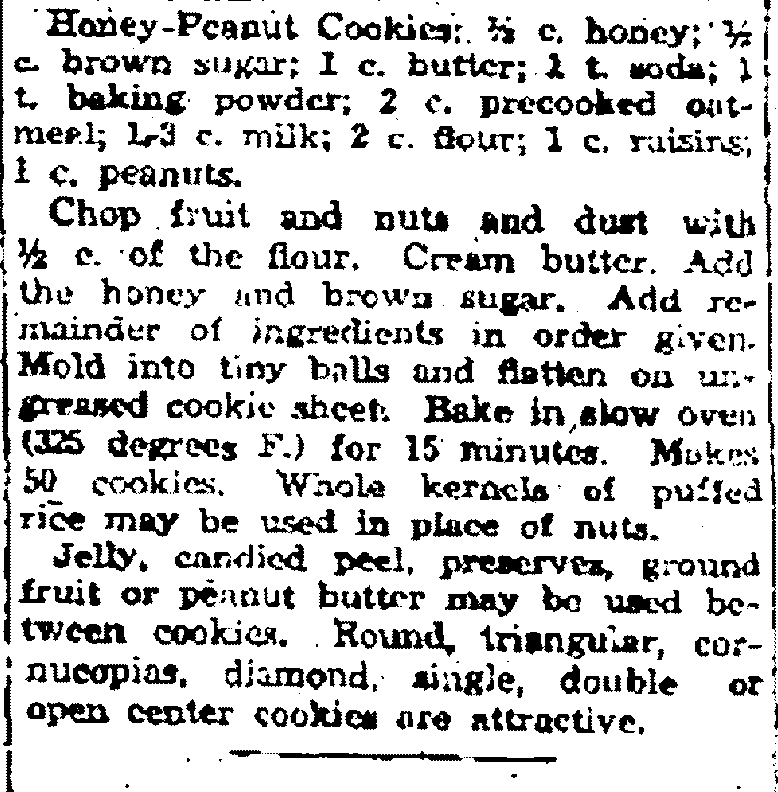

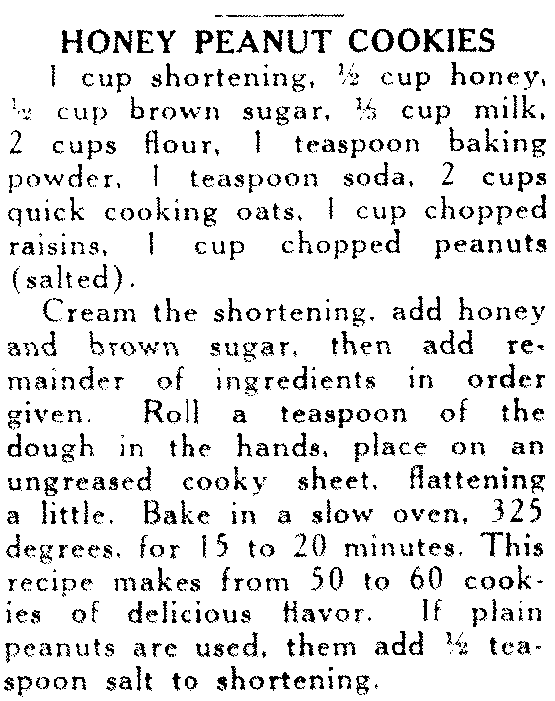

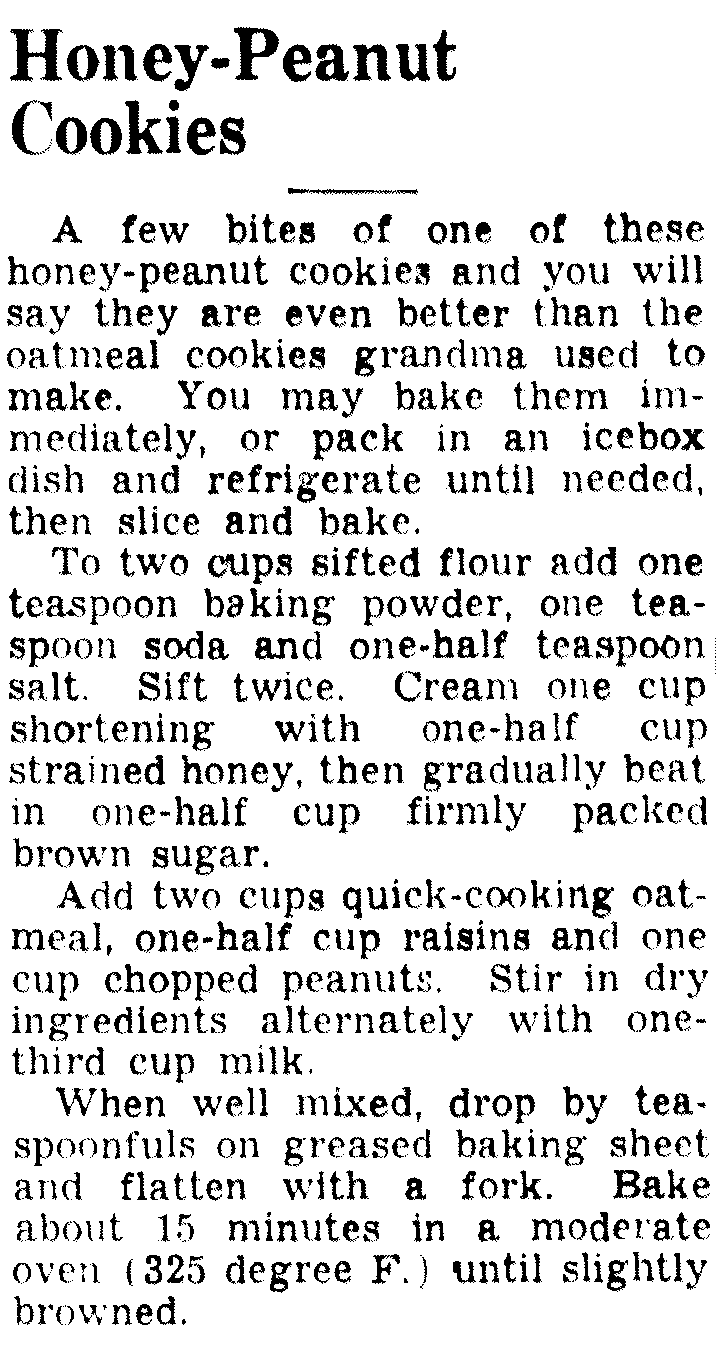

At the last minute before this post went live, I made the Prize Honey Peanut Cookies for a family reunion. At first I thought the lack of eggs might be a typo. That’s always a problem with the phrasing “then add the rest of the ingredients in the order given”. If there’s a typo in “the rest of the ingredients” this gives you no clue! But a search of old newspapers brought up a bunch of recipes like this from 1935 through 1945. At first I thought they might be a form of sandy, such as I wrote about in my potato chip cookies post.

The earliest of the recipes that I found was in the July 18, 1935, Lemoore, California, Advance. It differs only in the amount of soda (½ tsp instead of 1 tsp) and baking powder (2 tsp instead of 1 tsp). A year later, the same recipe appeared in the June 27, 1936, North Adams, Massachusetts, Transcript with the exact ingredients of the Westinghouse version—this is also the first of the recipes to call for “quick cook oats” instead of “rolled oats”—and the similar but not exact instruction to “Mix ingredients in order given”, with the note that it makes “35 to 40 cookies (2 to 2 1-2 inches in diameter).” In the December 9, 1936, Huron, South Dakota, Daily Plainsman, Olive Neff provides the recipe with instructions that match the Westinghouse recipe:

Cream butter. Add the honey and brown sugar. Add remainder of ingredients in order given.

She lists the oatmeal as “precooked oatmeal”, however. I almost have to think that this is what she calls quick-cooking oatmeal. From the 1936 Transcript on, all of the recipes call for quick-cook oats of some form.

Throughout this history of Prize Honey Peanut Cookies, the recipes have variations such as three cups oatmeal instead of two, or suggesting puffed rice in place of the peanuts, or using only half the raisins—a variation toward the end of World War II. The November 22, 1940, Punxsutawney Spirit has the interesting note that the peanuts should be salted, and if not salted, to “add ½ teaspoon salt to shortening.” This is echoed in later copies of the recipe in other newspapers.

In fact, they’re a very good oatmeal cookie, very much like the oatmeal cookies from this old Baker’s chocolate pamphlet or any number of community cookbooks from the seventies, but without the coconut. What they’re not, in any obvious sense, are refrigerator cookies. Unless the use of milk instead of egg is meant to highlight your ability to keep fresh milk on hand, there’s nothing in this recipe as written that shows off the capabilities of your refrigerator.

I suspect they were included because oatmeal cookies are just plain so good that the editor couldn’t resist. But there is one sense in which these would be a great refrigerator sales tool. Like the refrigerator biscuits, they could presumably be made without the milk and then stored indefinitely in the refrigerator to have cookies-on-demand. Just add milk sufficient to turn it into a cookie dough. But the recipe and book make no mention of this as a possibility.

Honey Peanut Cookies from 1935 to 1944.

Like the earlier and later refrigerator books, the refrigerator is still expected to be used as a cooking appliance as well as a storage medium.

In the pages that follow, you will find brief instructions for the storage of foods, and for the use of the temperature regulator followed by general suggestions and specific recipes to use in preparing frozen desserts, chilled desserts, beverages, breads, leftovers and salads.

The ideas offered are kitchen tested. Those for frozen desserts have been improved to meet the changes and improvements in Westinghouse Refrigerators. The fast freezing which is now possible enables you to make simple frozen desserts containing no cream or thin cream, which surpass those which could previously be made only with expensive whipped cream. All the recipes in this book may be so easily prepared that even an inexperienced cook may make them.

When is the last time you adjusted your refrigerator’s dial to match the needs of a particular dish?

There are also still remnants of what I call the early home computer ethos that permeated the manuals from the previous decade. Edna I. Sparkman’s introduction ended with the admonition that:

This is your book and we hope that it will help you to enjoy using your Westinghouse Refrigerator.

“This is your book” is not in the forties refrigerator books, and certainly not in modern ones. The latter part of the sentence does appear in various forms in the manuals of some cooking appliances, but refrigerators are no longer cooking appliances. “This is your book” is pure early home computer. The early refrigerator, like the early computer, is meant to make your life easier. We don’t know what you’re going to do with it, but it is your right and responsibility to find out.

In response to Revolution: Home Refrigeration: Nasty, brutish, and short. Unreliable power is unreliable civilization. When advocates of unreliable energy say that Americans must learn to do without, they rarely say what we’re supposed to do without.

Since I don’t have pets or a “particularly greasy or dusty” environment, but also can’t see how the refrigerator would care whether that dust accumulated slowly or quickly, I have it on my calendar to clean it every two years.

↑If you look in the book, you’ll see that it doesn’t specify what size package of cream cheese to use. Both 3 ounce and 8 ounce packages of cream cheese were common then. I’ll update this the next time I make it, but I suspect a three ounce package. That seems about right for two tablespoons of candied ginger, and it also somewhat matches the amount that the next recipe in the book would make.

I do not remember what I used, but it was probably the leftovers from an 8-ounce package.

Update, September 13, 2025: It almost certainly means a 3-ounce package. I made it again this morning using 4-½ ounces of leftover cream cheese and one tablespoon (i.e., half of two tablespoons for a half recipe of spread) was much too sparse. Two more tablespoons (i.e., 1-½ times two tablespoons, for a +50% recipe) was about perfect.

↑

cookbooks

- The Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved Refrigerator Book at Lulu storefront (paperback)

- Originally published by the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company of Mansfield, Ohio, ca. 1937. “This is your book and we hope that it will help you to enjoy using your Westinghouse Refrigerator.”

- The Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved Refrigerator Book (PDF File, 11.6 MB)

- A ca. 1937-38 Westinghouse refrigerator operating instructions, kitchen guide, and recipe book.

history

- Historical Statistics (Colonial to 1957) at United States Census Bureau

- “Preparation of historical tables showing energy from various sources and total energy input on a per capita or other basis is complicated. The amounts shown will differ greatly depending on the basis and point of measurement used.”

- Origin of “spring cleaning”

- “Here in chronological order, are the earliest matches for ‘spring cleaning’ from a Google Books search of works published before 1860.”

refrigerators

- Getting the Most from an Electric Refrigerator at Internet Archive

- Homemaker News Number 179, June 30, 1937, from the United States Department of Agriculture, describing how to best use home refrigerators.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1928 Frigidaire

- The 1928 manual and cookbook, Frigidaire Recipes, assumes a lot about then-modern society that could not have been assumed a few decades earlier.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

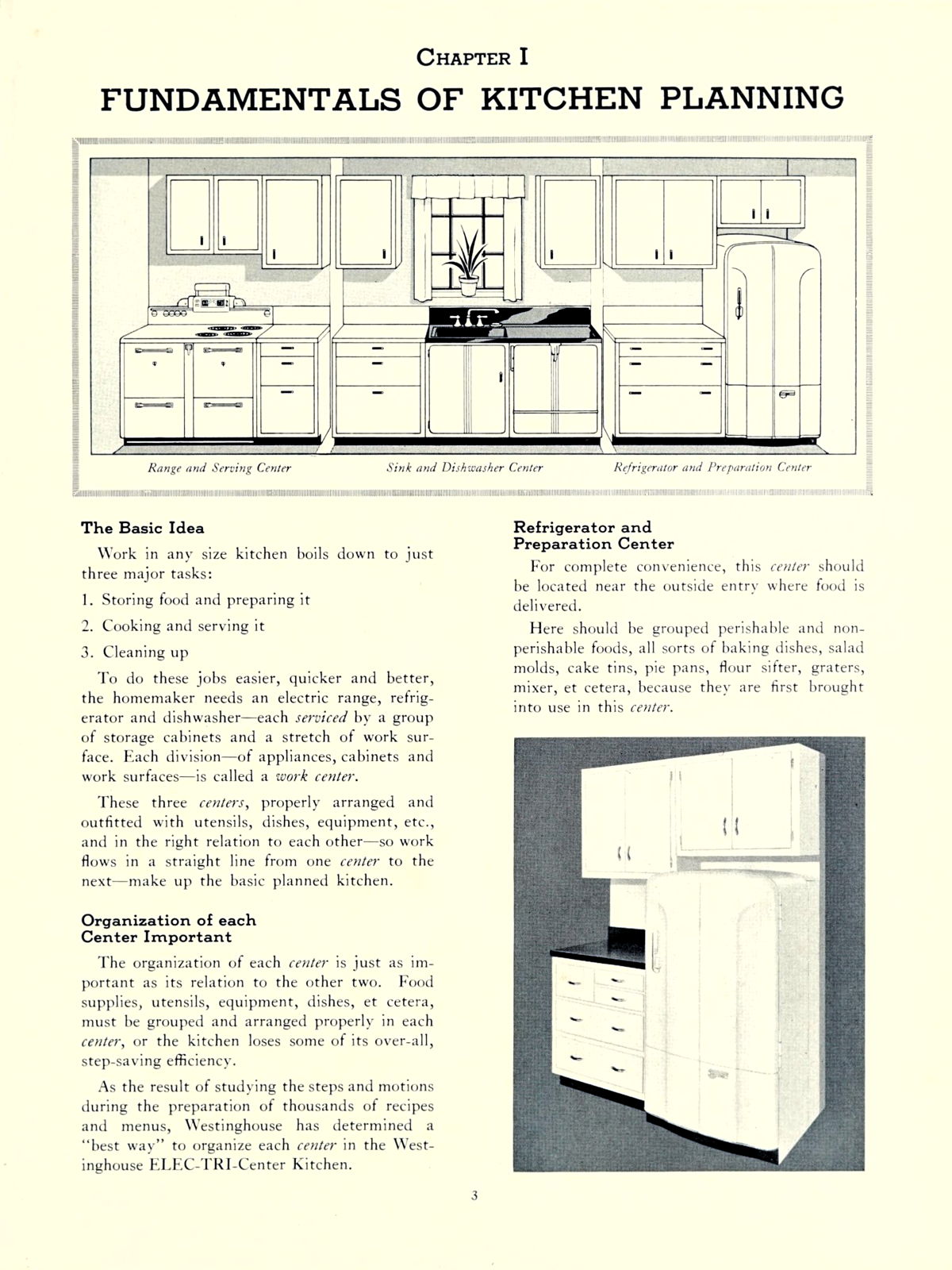

- Westinghouse Kitchen Planning Manual at Internet Archive (ebook)

- “A practical book of Kitchen Planning Fundamentals and Standard Kitchen Plans for architects, kitchen engineers, builders and complete electric kitchen retailers.”

food

- Jalapeño Potato Chip Cookies

- Potato chip cookies are amazing—crunchy and flavorful—and they’re even better made with kettle-style jalapeño chips! Potato chip cookies are a great way to celebrate National Potato Day.

- Baker’s Dozen Coconut Oatmeal Cookies

- The Baker’s Dozen coconut oatmeal cookies, compared to a very similar recipe from the Fruitport, Michigan bicentennial cookbook.

- The Gallery of Regrettable Food: James Lileks

- “The Internet’s home for Peculiar Comestibles since 1997.”

- Review: The Joy of Cooking: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This edition of Irma Rombauer’s influential book is old enough to be at the dawn of chocolate chips.

More cookbooks

- Using ingredients to guess cookbook years

- Community cookbooks often call for brand name products and tools. That can provide a lower bound for what year a book was published, but rarely an upper bound.

- My Year in Food: 2025

- My year in food extended from 1776 to 2026, from San Diego to Barcelona, and from Texas to Michigan. I also made several vintage books available for you to download!

- Padgett Sunday Supper Club Sestercentennial Cookery

- The Sestercentennial Cookery is a celebration of American home cooking for the 250th anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence.

- Cookbook publication year estimates I have made

- When I acquire a cookbook without a publication or copyright year, I use the advertisements and contributors to make a stab at the likely year of publication. This page provides those guesses in case it helps you date your own books.

- Four New Ices and an Ice Cream Cookery

- Philadelphia Ice Cream, Walnut Nougat, Lemon Cream Sherbet, and Cranberry Ice. Four more new no-churn ice creams and desserts for Summer 2025. And, a book collecting all my favorite no-churn ice creams if you’re interested!

- 75 more pages with the topic cookbooks, and other related pages

More food history

- Using ingredients to guess cookbook years

- Community cookbooks often call for brand name products and tools. That can provide a lower bound for what year a book was published, but rarely an upper bound.

- Hot ovens: Bakers were once the slaves of time

- We have chained time in our kitchens. Our refrigerators stop time from destroying food, and our ovens lash it to the oars for baking. And we have forgotten that it was ever any other way.

- Using archives to guess cookbook years

- Many cookbooks, especially community cookbooks and often advertising pamphlets, leave off the year. Online newspaper and magazine archives can help to narrow down when the book was published.

- Padgett Sunday Supper Club Sestercentennial Cookery

- The Sestercentennial Cookery is a celebration of American home cooking for the 250th anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence.

- Table and Kitchen: Baking Powder Battle

- The Royal Baking Powder Co. was a very combative entrant in the baking powder wars. But that kind of competitive spirit can also mean great recipes.

- 28 more pages with the topic food history, and other related pages

More Refrigerator Evolution

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1928 Frigidaire

- The 1928 manual and cookbook, Frigidaire Recipes, assumes a lot about then-modern society that could not have been assumed a few decades earlier.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1947 Cold Cookery

- The 1947 Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest reflects not just increased access to electricity but also the end of a second world war.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1927 Electric Refrigerator Menus & Recipes

- The very first modern refrigerator/freezer came with a very revelatory cookbook that treated customers nearly the same way computer manuals would exactly fifty years later: as partners in a revolutionary new means of creativity.

- My Year in Food: 2025

- My year in food extended from 1776 to 2026, from San Diego to Barcelona, and from Texas to Michigan. I also made several vintage books available for you to download!

More refrigerators

- Hot ovens: Bakers were once the slaves of time

- We have chained time in our kitchens. Our refrigerators stop time from destroying food, and our ovens lash it to the oars for baking. And we have forgotten that it was ever any other way.

- Refrigerator Revolution Reprinted: 1928 Frigidaire

- If you’d like to have a printed copy of the 1928 Frigidaire Recipes, here’s how you can get one. Also, a lot of new recipes tried.

- Four New Ices and an Ice Cream Cookery

- Philadelphia Ice Cream, Walnut Nougat, Lemon Cream Sherbet, and Cranberry Ice. Four more new no-churn ice creams and desserts for Summer 2025. And, a book collecting all my favorite no-churn ice creams if you’re interested!

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1947 Cold Cookery

- The 1947 Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest reflects not just increased access to electricity but also the end of a second world war.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1942 Cold Cooking

- Iceless refrigeration had come a long way in the fourteen years since Frigidaire Recipes. And so had gelatin!

- Three more pages with the topic refrigerators, and other related pages