Economic misterminology: recessions that never end

I’ve been reading a lot about how the Great Recession is over in the United States, and that, therefore, Americans should not feel as economically pessimistic as we do. The most recent was an article by James Pethokoukis in the October Commentary.

The problem with this line of reasoning—the recession is over, thus everyone should be happy about it—is that it misuses economic terminology. The meaning of recession for economists is very different from the colloquial use of the term. This is not necessarily the fault of the journalists misusing the terms. Economic terms seem to be designed to cause confusion. If you read this blog regularly, you’ve read my complaints about how politicians use the term “austerity”. Countries raise taxes and sometimes even increase spending, their economies fail to recover and often get worse, and therefore, austerity has failed. Which is only true because austerity has been defined to include raising taxes and spending more. Raising taxes and spending more is not what most people mean when they use the word “austerity”.

The same is true of recessions. And it’s not completely the fault of economists. Determining when a recession begins and when a recession ends should mean having a long and probably rancorous discussion about what caused the recession and how long it took that cause to have an effect. This would inevitably lead to passing blame, because whatever those causes were, someone had a hand in creating them. For whatever reason, economists avoid this by using a purely mathematical definition of when a recession started and when it ended.

When was the economy doing the best? That’s when the recession started. When was the economy doing the worst? That’s when the recession ended. I’m not exaggerating that. Once the determination has been made that we are in a recession, economists look back to when we were doing best, and that’s when they define the recession as having started—even if that point comes before the event that triggered the recession. Once the determination has been made that the recession is over—which, itself, is a purely mathematical determination that does not have to have any connection with what people think a recession means—economists look back to when we were doing the worst, and that’s when the recession ended.

That’s literally it: around September of 2010, the National Bureau of Economic Research decided that the recession had ended. They then looked backward for the “low point”, which they found in July 2009:

The bureau took care to note that the recession, by definition, meant only the period until the economy reached its low point—not a return to its previous vigor.

“It’s always darkest before the dawn” is a writer’s cliché, but it’s an economic truism. When your life sucks the most, congratulations! You are no longer in a recession.

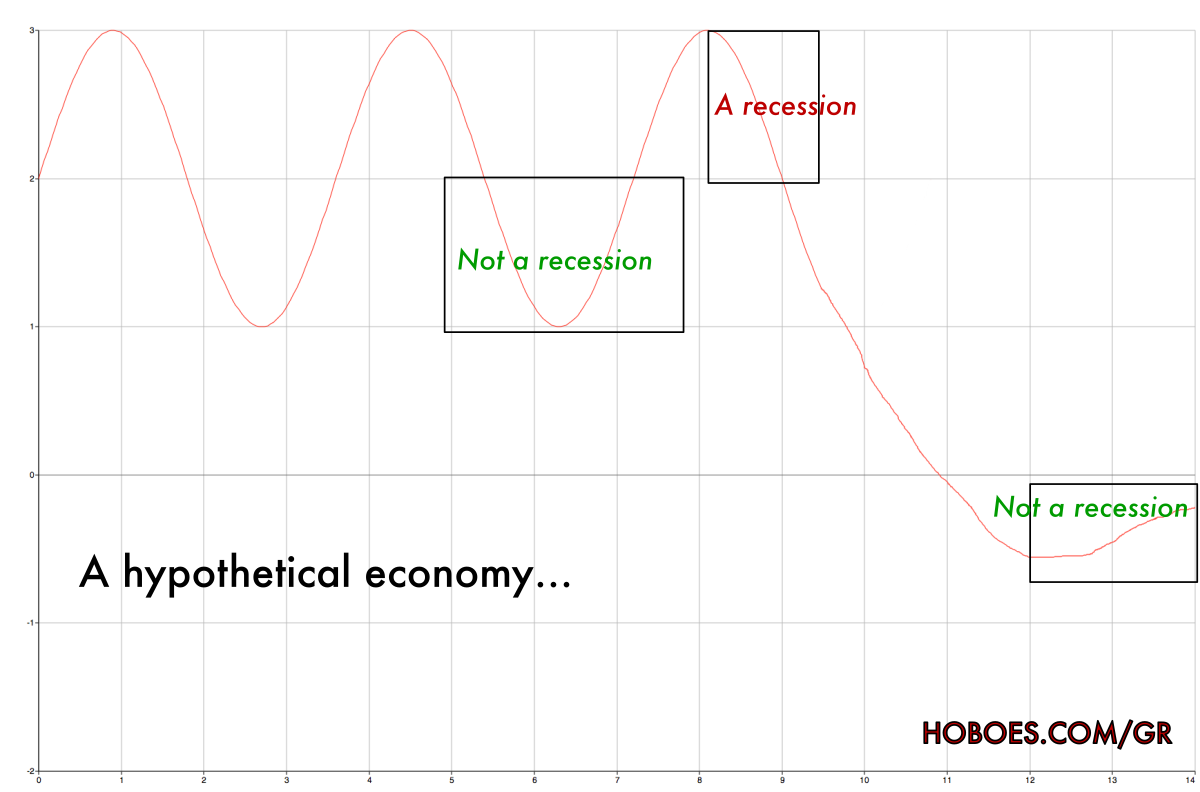

This definition is extremely problematic not just because it defines a recession in a way that ignores the economy’s effects on the people in it, but also because it ignores the natural cycles of an economy.

The definition of a recession is that it starts when you’re doing as well as or better than ever, and it ends when you’re doing worse than ever.

According to the definition of recessions, this hypothetical recession started at the last top of the economic cycle. But at that point, the economy wasn’t doing anything out of the ordinary. To call that period a part of the recession makes the concept of recession almost completely useless. It’s entirely likely that the event which triggered the recession had not even occurred when the recession officially started.

Similarly, for most people the end of a recession is when we return to that normal cycle. To say that the recession is over when we’re still way below the normal cycle is not just to define the term completely uselessly but to define it in a very confusing manner.

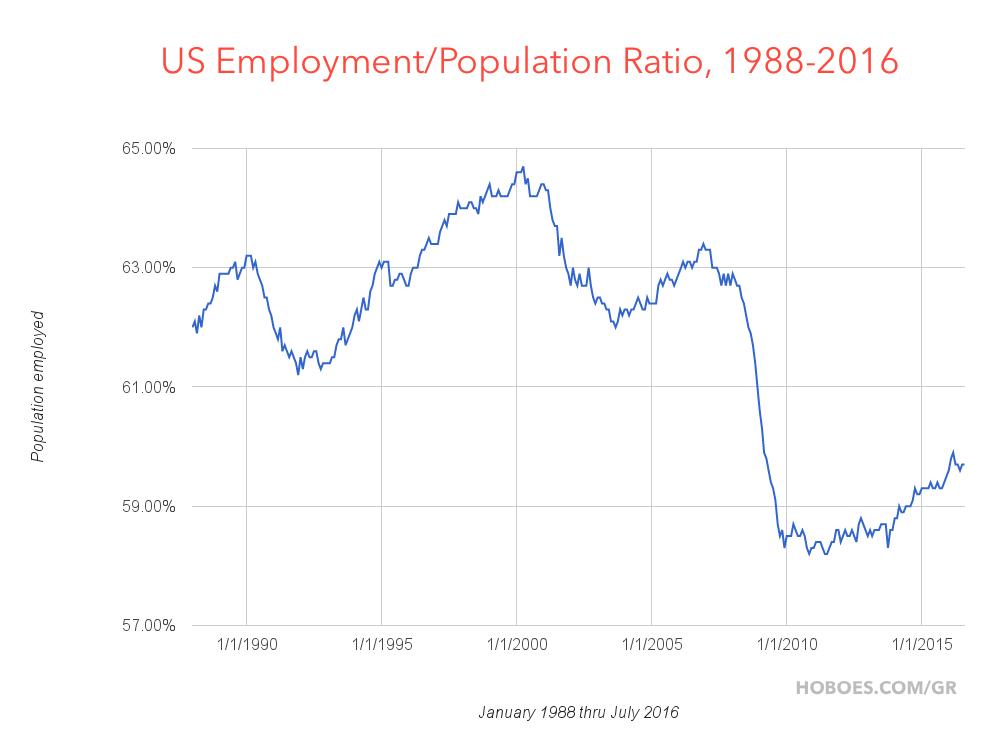

Here, for example, is the employment/population ratio for the last several years; it looks a lot like the hypothetical economy. According to economists, the Great Recession ended seven years ago.1 You can see it on the chart: that’s when the employment rate began its very slow rise.

Sure, the recession’s been over for seven years. (multpl.com)

The reason Americans don’t feel that the recession has ended is that despite that slow rise, we’re nowhere near the employment rate we were at even in the low points of the economic cycle before the recession hit. Americans understandably don’t feel like we’re out of a recession because they don’t yet have a job, or know so many more people who don’t have a job. This is not a fact that requires reexamination of people’s psychology. This is a statistic that requires reexamination of how the statistic was acquired.

Pethokoukis’s article has an example of how the near-complete ignorance of triggering events means we ignore very important events regarding the economy—events that we can affect. He talks about how people seem to ignore that our most pessimistic times seem to be followed by economic expansion:

Each bout of pessimism was followed by economic expansion and an upsurge of optimism and national morale. The volatile 1970s reached their emotional nadir 16 months before Jimmy Carter’s reelection defeat, with his “malaise” address. In Ronald Reagan’s 1979 speech, which launched his presidential bid, Carter’s successor said, “They tell us we must learn to live with less, and teach our children that their lives will be less full and prosperous than ours have been; that the America of the coming years will be a place where—because of our past excesses—it will be impossible to dream and make those dreams come true. I don’t believe that. And I don’t believe you do, either.”

Reagan was speaking at a time when fewer than a fifth of Americans were satisfied with the country’s direction, according to Gallup. Country singer-songwriter Merle Haggard had a 1982 hit called “Are the Good Times Really Over?” That reflected the nation’s apparently permanent funk. But that was followed in relatively short order by “Morning in America” and the Reagan boom.

…

The lesson these examples seemed to have taught us was that when trouble came, you had to buck up, be patient, and wait for the sputtering American Growth Machine to shift back into high gear. If you sold America at the bottom you were a sucker.

Now, some economic downturns have more-difficult-to-discern triggers. But just being patient would not have helped end the downturn of the seventies.2 The reason that downturn ended is because the American people chose to change course, and elect a Reagan rather than a Nixon or a Carter. While there may be valid arguments for one or another thing starting or ending other downturns, there is very little argument about what ended the downturn of the seventies: Reagan repealed the Nixon/Carter oil price controls. Partisans can argue all they want about whether other actions in the Reagan era helped or hurt the economy, but there is no question that removing price controls in January 1981 helped.

Reading the New York Times article bemoaning the end of price controls is darkly hilarious. Just as when the AT&T government monopoly was ended, the New York Times forecast higher prices. The actual effect was for the cost of energy to drop drastically… allowing the economy to start rising again.3

Nowhere is this mentioned in the Commentary article. The implication is that there are cycles, and it didn’t matter that the American people chose to change course. If they’d just been patient, the downturn would have ended just the same.

Which is not just bullshit but dangerous bullshit. It is dangerous to pretend that there are no causes and effects. If the American people hadn’t changed course, Congress would have extended price controls past 1981—probably made them permanent—and we would be an energy-destitute nation today, with all the secondary effects that would have on our economy.

In the unlikely event that a Republican wins in November and the Republican Congress chooses to repeal the ACA and its onerous controls over health care, the New York Times will write yet another editorial bemoaning the coming explosion in health care costs. And the New York Times will, again, be wrong.

The lesson of that particular example is not “be patient”, it’s “don’t elect politicians who think government needs to control the market.” The market is the American people. Attempts to control the market are attempts to control people. Leave the American people free to succeed, and they will.

More and more, Chauncey Gardiner is looking like an economic genius.

In response to Beware the Austerity of the Politician: Austerity, to politicians, doesn’t mean what you think it means.

By similar reasoning, the Great Depression ended in 1933, despite years of bad economy from 1933 on.

↑I may very well be misunderstanding Pethokoukis’s point; he is normally a very concise and clear writer, but I found this article to be muddled and meandering, which may mean that I’m missing some key point that ties it all together.

↑The price of oil dropped by more than 50% after Reagan removed the price controls on it. Every company in the United States that relied on energy—which is to say, every company in the United States—was able to expand, hire more workers, pay workers more, and/or charge less for their products. Every person in the United States was able to buy more for the same amount of money and have more left over after paying for necessities. Everything relies on energy.

↑

- The austerity of the drunkard

- If you’re an alcoholic and you redefine “abstinence” to mean “drink more”, you might very well solve your drinking problem: by killing yourself.

- Capitalism is not an ism

- Capitalism is not a system—it’s just what people do when they get together peacefully. When people complain about capitalism, they’re really saying that they want more power over what people do when they get together peacefully.

- How Bad Is the Great American Slowdown?: James Pethokoukis at Commentary

- “The lesson these examples seemed to have taught us was that when trouble came, you had to buck up, be patient, and wait for the sputtering American Growth Machine to shift back into high gear. If you sold America at the bottom, you were a sucker.”

- Natural monopolies: a 20-minute call for $8.83

- “A 20-minute call anywhere in the country will cost me only $3.33? What’s the catch?” The catch is that those are still outrageous monopolistic prices.

- President abolishes last price controls on U.S.-produced oil: Robert D. Hershey Jr. at The New York Times

- “President Reagan today abolished the remaining price and allocation controls on domestic oil and gasoline production and distribution, carrying out a pledge to end what the Administration regards as counterproductive Federal regulations of the oil industry. As a result of the President's executive order, the cost of gasoline and heating oil is expected to rise, but analysts differed about the amount.”

- The Recession Has (Officially) Ended: Catherine Rampell at The New York Times

- “In determining that a trough occurred in June 2009, the committee did not conclude that economic conditions since that month have been favorable or that the economy has returned to operating at normal capacity,” the bureau said. “Rather, the committee determined only that the recession ended and a recovery began in that month.” (Memeorandum thread)

- Second look at Chance the gardener

- Is President Obama really a mentally-challenged private gardener who has never left his DC townhouse?

- US Employment Population Ratio

- “The US Employment Population Ratio (or Employment to Population Ratio) indicates the percentage of the total US working-age population (age 16+) that is employed. Unlike the Unemployment Rate, this includes people who have stopped looking for work.”

- The Vision of the Anointed

- Would you believe that good intentions can defy the law of gravity? If not, you wouldn’t make a good politician in today’s America.

More misleading terminology

- The left’s hatred of business is a lie

- The left doesn’t hate business. They hate you and me.

- Pluto is not a planet, and other respectable murders

- If Pluto is not a planet, and tomatoes are not vegetables, then austerity can mean higher taxes and more spending.

- Austerity really means raising taxes

- When Paul Krugman claims that austerity is a failure, he defines it as cutting spending; but in fact, his examples are all of countries that raised taxes often along with raising spending.

- Austerity is not the only answer

- According to the Financial Times, Austerity is not the only answer to a debt problem. The other answer is a paywall.

- The austerity of the drunkard

- If you’re an alcoholic and you redefine “abstinence” to mean “drink more”, you might very well solve your drinking problem: by killing yourself.

- Four more pages with the topic misleading terminology, and other related pages

More recession

- Pluto is not a planet, and other respectable murders

- If Pluto is not a planet, and tomatoes are not vegetables, then austerity can mean higher taxes and more spending.

- Garbage in, garbage out economics

- Given the pointless definition of a recession, is it any wonder people are confused about the recovery?

- Definitionally dodging recession responsibility

- You’re in a recession when the economy’s doing well; you’re out of it when the economy sucks. Ignore that mortgage crisis behind the curtain.