Natural monopolies: a 20-minute call for $8.83

A few years ago, I received an old TV Guide from 1981 as a gift. There were a lot of fun things in it, such as Bosom Buddies, giant murals of flying horses through rainbows, the sort of stuff you expect from the late seventies and early eighties.

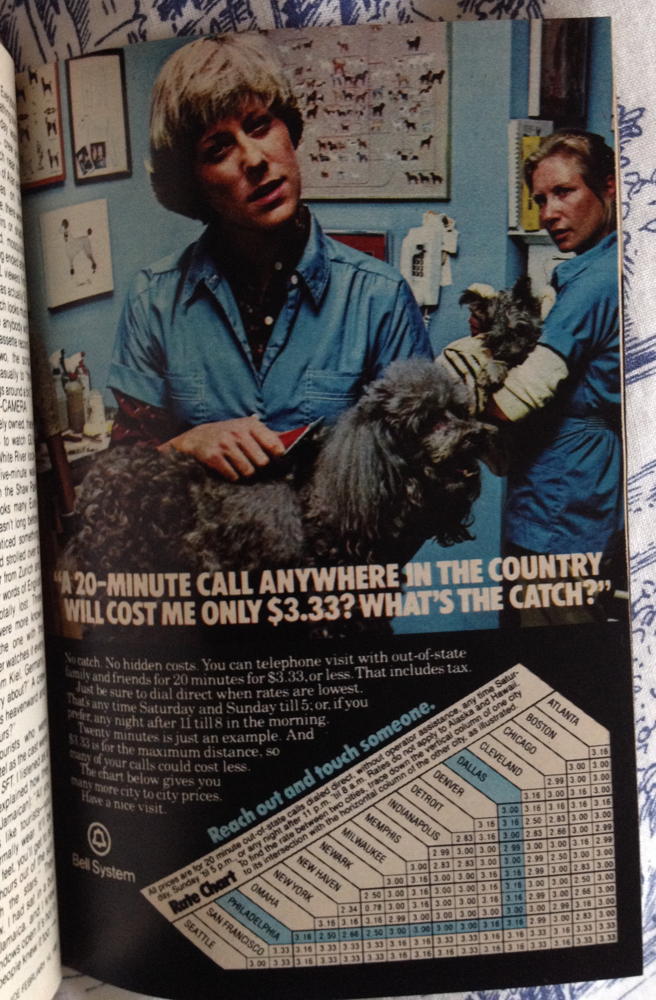

There was also this ad from AT&T’s “Bell System” touting the incredibly low price of $3.33 per twenty minutes. In 1981, AT&T had a monopoly on phone service. That $3.33 per 20 minutes is, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation calculator, $8.83 per 20 minutes, or $26.49 per hour.

And read the fine print: that’s just the off-hours cost.

That’s any time Saturday and Sunday till 5; or, if you prefer, any night after 11 till 8 in the morning.

Today, even on AT&T, you only pay $1.40 per 20 minutes1, and you don’t have to worry about peak vs. off-peak hours. That’s if you still have a land-line. More likely, if you have a cell phone, you don’t even worry about minutes anymore.

I remember having to time my long-distance calls home in order to avoid incurring the “peak rate”: calling early in the morning, usually, because my parents went to bed before 11 PM, then remembering to say goodbye before 8 AM.

You can still see the vestige of it in AT&T’s “basic rates”, which are the rates you pay if you have AT&T but for some reason you don’t have a long-distance plan. Even those are, during off-peak hours, only $3.00 per 20 minutes. That would be as if AT&T’s highest off-peak cost in 1981 were $1.13.2

AT&T was a government-sponsored monopoly. I can just barely remember when we weren’t even allowed to plug in our own phones. I remember being happy that I could find an inexpensive “Conair” telephone when I was in college, so that we could have a phone in our apartment.

Up until the monopoly was ended in 1984, the phone system was considered by many to be a “natural monopoly”, just like water, electricity, mail, and roads. It was hard to imagine, then, what would happen when that “natural monopoly” was allowed to face competition. Even Reagan’s Defense Secretary, Caspar Weinberger, argued against it. Andrew Pollack in the New York Times on January 1, 1984, the day the monopoly officially ended, began his article gloomily:

A new era for American telecommunications and for American business begins today as the once-unified Bell System begins life as eight separate companies. It is a time of great expectations and great concern for both the telephone industry and the nation as a whole.

No company so large and technologically integrated as the Bell System has ever split itself into pieces before, not even in the great trust-busting days early in the century.

No nation has ever made a determination to let the forces of competition, rather than government-backed monopoly, determine the future of something so vital as its telephone network. It is an especially daring course for the nation that, by almost all accounts, already has the best phone system in the world. If the gamble is lost, quality of telephone service could deteriorate.

He followed this opening by quoting Alfred D. Chandler3 that,

“To break up a very tight network is something quite unprecedented,” said Alfred D. Chandler Jr., professor of business history at the Harvard Business School. “It was one of the best managed companies in the world for a long time. You go overseas and people there can’t understand why we’re breaking up A.T.&T.”

Chandler wasn’t the only one who thought it a bad idea.

“It is the dumbest thing that has ever been done,” said Charles Wohlstetter, chairman of Continental Telecom Inc., an independent telephone company. “You don’t have to break up the only functioning organization in the country to spur innovation.”

Pollack writes that, even though telephone service is likely to deteriorate, some customers might prefer the lower quality if they can pay less.

In addition, the opponents argue, with no company having responsibility for end-to-end communications and with each company cutting corners to lower costs, the quality of telephone service will deteriorate.

…

But such potential drawbacks could be balanced out by reduced long-distance rates and by the money people can save by buying their phones rather than renting them. In addition, many people might prefer lower quality phone service if they can pay less.

The idea that competition would lead to both higher quality and lower prices is almost never considered when talking about ending a monopoly. Pollack even writes about how breaking up monopolies is likely to price poor people out of the services. Instead, even households below the poverty line have far better phone service today than they had in 1981.

This attitude in favor of government control of the economy wasn’t new. I was surprised, reading A.M. Sperber’s biography of Edward R. Murrow, by the high-ranking officials in the United States government lamenting the inevitable Soviet economic triumph. They could not believe that a free people in a free market could see greater economic growth than a government-planned economy.

That attitude persists even today, despite planned economies producing nothing but poverty, misery, and corruption compared to free people freely buying and selling.

Nowadays, because we have seen the results it’s hard to imagine phone service as a natural monopoly. In my close circle of friends, I’m not even sure any of us have the same service. I don’t know, and I don’t care. We each of us choose the service that best suits us.

There are still people who don’t believe electricity can be de-monopolized despite its success in places like Texas. They see the mess that governments have made of electrical monopolies but can’t imagine it ever getting better.

After moving to Texas and paying less for higher quality, I can’t imagine going back to a California-style monopoly. The process of hooking up electricity here was so much easier than any dealings I’d had in California. I handled the entire hookup by a web page, and had it scheduled down to the day I arrived. It worked flawlessly.

The FDR-era Communications Act of 1934, which, among other things, centralized the regulations that made AT&T’s monopoly feasible, had:

…the purpose of regulating interstate and foreign commerce in communication by wire and radio so as to make available… a rapid, efficient, Nation-wide, and world-wide wire and radio communication service with adequate facilities at reasonable charges…

The evolution of telephone service after the monopoly ended shows that the monopoly completely failed in that purpose. The AT&T monopoly was neither rapid, nor efficient, nor, in retrospect, available at reasonable charges.

We simply do not know what we’re missing, and how life could be better, by ending government and government-sponsored monopolies, in power, in cable television, in education, in letter delivery, possibly even in water and roads. I don’t know how such services could be de-monopolized, but I’ve seen enough other “natural monopolies” turn out to have been unnatural cronyism that I’m not going to say it can’t be done.

In response to 2016 in photos: For photos, memes, and perhaps other quick notes sent from my mobile device or written on the fly during 2016.

Seven cents a minute, according to their website, if you pay $5 per month for their “One Rate” long distance plan.

↑Again, according to the BLS inflation page, this time going backward from 2016 to 1981.

↑Known for arguing, in The Visible Hand that bureaucratic development drives society forward.

↑

- Bell System Breakup Opens Era of Great Expectations and Great Concern: Andrew Pollack at The New York Times

- “No nation has ever made a determination to let the forces of competition, rather than government-backed monopoly, determine the future of something so vital as its telephone network. It is an especially daring course for the nation that, by almost all accounts, already has the best phone system in the world. If the gamble is lost, quality of telephone service could deteriorate.”

- The Breakup of Ma Bell: Bob Adelmann

- “In fact, without government regulations eliminating the competition, the reinstitution of the AT&T monopoly would have been impossible. The Kingsbury Commitment was an agreement with the Attorney General and the Interstate Commerce Commission in 1913 that essentially codified the playing field which allowed AT&T to regain monopoly control of the industry.”

- Communications Act of 1934 at Wikipedia

- “The Communications Act of 1934 is argued by some to have created monopolies, such as the case of AT&T. The FCC recognized AT&T as a ‘natural monopoly’ during the 1930s in the Communications Act of 1934.”

- Communications Act of 1934 (PDF)

- “For the purpose of regulating interstate and foreign commerce in communication by wire and radio so as to make available, so far as possible, to all the people of the United States, without discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex, a rapid, efficient, Nation-wide, and world-wide wire and radio communication service with adequate facilities at reasonable charges, for the purpose of the national defense, for the purpose of promoting safety of life and property through the use of wire and radio communication, and for the purpose of securing a more effective execution of this policy by centralizing authority heretofore granted by law to several agencies and by granting additional authority with respect to interstate and foreign commerce in wire and radio communication, there is hereby created a commission to be known as the ‘Federal Communications Commission,’ which shall be constituted as hereinafter provided, and which shall execute and enforce the provisions of this Act.”

- CPI Inflation Calculator

- Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation calculator.

- Health care reform: walking into quicksand

- The first step, when you walk into quicksand, is to walk back out. Health providers today are in the business of dealing with human resources departments and government agencies. Their customers are bureaucrats. Their best innovations will be in the fields of paperwork and red tape. If we want their innovations to be health care innovations, their customers need to be their patients.

- Murrow: His Life and Times

- Edward R. Murrow inspired generations of journalists with his reports from the London blitz on radio and, later, his reports on McCarthyism on television.

- TXU bets against deregulation and loses

- TXU was once the government-sponsored monopoly energy provider in Texas. They just went bankrupt, apparently because they expected a free market to act like a government market.

More AT&T

- Break up the Postal AT&T

- We have no idea what we’re missing by barring competition to the United States Postal Service. We’re in the position we were in 1980 when proponents of government monopolies were warning us of the horrors of ending the AT&T telephone monopoly.

More government monopolies

- Deadly complications of government bureaucracy

- Government monopolies, whether government agencies or de facto government agencies in the form of government-sponsored enterprises, aren’t rewarded by getting product to the people who need it. They’re rewarded by kissing up the bureaucratic chain.

- COVID Lessons: How can we respond to a disease before it spreads?

- How can we make ourselves less vulnerable to sudden epidemics, before they become epidemics, and without causing epidemic levels of deaths?

- COVID Lessons: Government Monopolies are Still Monopolies

- Our response to COVID-19 was almost designed to make it worse. We shut down the nimble small businesses that could respond quickly, and relied almost solely on large corporations and the government monopolies that failed us, because they are monopolies.

- A free market in union representation

- Every monopoly is said to be special, that this monopoly is necessary. And yet every time, getting rid of the monopoly improves service, quality, and price. There is no reason for unions to be any different.

- Why is it so difficult to hold schools accountable?

- Simulating accountability in education has the same problems as simulating accountability in health care or any other monopoly. Tests and grades and paperwork are never as effective as choice.

- Two more pages with the topic government monopolies, and other related pages

More telephones

- The lost tradition of unannounced visits

- Once upon a time, if you were in the area of a friend, and you had extra time, you’d just drop in for a visit. You wouldn’t call first—phone calls were expensive. You wouldn’t text—there were no texts. You’d just show up. And you’d be even more likely to do this on holidays.