Table and Kitchen: Baking Powder Battle

Also available in print.

Tomorrow is Christmas, and have I got a gift for you! I was driving across Missouri when I found this tiny little 1916 pamphlet/book in a library sale’s discount box. And by “discount”, I mean anything in the box was ten cents.

The full title is Table and Kitchen: A Practical Cook Book (PDF File, 15.3 MB). It’s an advertisement for the Royal Baking Powder Company’s “Dr. Price’s Cream Baking Powder”. Dr. Price’s was a single-action baking powder, that is, it did not contain alum. It used only cream of tartar as the acid.

While the cover is wonderful my initial thought was to leave it. I’m not a huge fan of how recipes were written in that era. I’ve seen other baking powder cookbooks, and have not been impressed by them. Further, there was practically no cell service in the area, so I couldn’t look up whether the book had been scanned online or not yet. But at ten cents I decided I couldn’t leave it: its next stop would certainly have been the recycling bin out back.

When I got to the hotel that night, I discovered that (a) it was not yet available anywhere, which meant I would at least get a good blog post out of it, and (b) there were a lot of very interesting, if sparsely-described, recipes inside.

One particular aspect of these old recipes that annoys me is a tendency to use what I call reverse Polish notation, or, as my gamer friends would say, Hastur he who must not be named oh shit. I wrote about the same writing “technique” in A Vicennial Meal for the Sestercentennial and Table and Kitchen’s eggnog recipe is a good example of the form:

Egg Nog. —Six eggs well beaten (white and yolks separately), one quart milk, one-half cup sugar, one cup brandy, nutmeg. Stir yolks into milk, with the sugar first beaten with yolks. Add brandy, then whites of eggs. Whip well.

Why in the world didn’t they write “Beat the sugar with the yolks, then stir into the milk.”? I came close to adding the yolk to the milk and then discovering I should have beaten the yolks with the sugar first. I realize it’s my own failing, but I am a very literal recipe reader when I first make a new recipe.

The first three recipes I tried, in fact, were all real winners, although at least one required a whole lot of interpretation.

The Green Pepper Catsup was the first, and wow! It’s very simple. Green peppers (“the hot variety”); cloves, allspice, and mace; onions; and vinegar. The amounts are horribly vague. How many green peppers fit in a “kettle of ten pounds capacity”? Does that mean four and a half quarts? I.e., ten pounds water? Google’s AI seems to think that a ten-pound capacity kettle is a piece of exercise equipment, and I guess making a full recipe of this would indeed be serious exercise!

I made a ¼ recipe using jalapeños and assumed that a full recipe was five quarts (it made the math easier). In keeping with my softly-held theory that old recipes often leave out the salt that they assume is already there, I added a half teaspoon of salt (i.e., four teaspoons for a full recipe). Because I guessed that this was going to be insanely hot, I also added a tablespoon of sugar (i.e., a quarter cup for a full recipe).

Green Pepper Catsup

Servings: 2

Preparation Time: 1 hour

Table and Kitchen (PDF File, 15.3 MB)

Ingredients

- 9 cups jalapeños (or other hot peppers)

- 2 large onions, chopped fine

- 1 quart vinegar

- 2 tsp salt

- ¼ cup sugar

- 1-½ tsp ground cloves

- 1-½ tsp ground allspice

- 1-½ tsp ground mace

Steps

- Mix ingredients.

- Boil, covered, until vegetables are soft and easily mashed.

- Sieve through a food mill to remove seeds and skins.

- Return to boil.

- Pour into warm sterilized jars (2 pint jars) and seal.

If you read the original recipe, there’s an odd instruction to “stew among the peppers”. I assumed that this was a typo for “strew among the peppers”. The next step assumes that the peppers are not yet “readily mashed” which implies that they are also not “stewed”. On the other hand, this could have been another example of reverse Polish notation, giving the instructions to stew before giving the instructions to add liquid. Fortunately, the end result of either assumption is the same: add the liquid. Then stew.

It is numbingly hot if slathered onto meat or a sandwich, but in smaller mounts it has a very nice flavor. It’s definitely a hot sauce with catsup spices. I ended up with three pints; I canned them like a relish, but with only tiny amounts of salt and sugar I stored it in the fridge. Probably with that much vinegar it would be fine in the cupboard, but this stuff was good enough I didn’t want to risk losing it.

The transparent pie, or eggnog pie as I call it, is absolutely wonderful.

When I made it a second time, I doubled the salt and sugar, and ended up with something even more like modern catsup but still very, very, hot. This is good, but I, at least, need to use it sparingly. It’s wonderful as a catsup on sandwiches but also for adding flavor to stews, casseroles, or soups.

The Transparent Pie has been a hit even outside my kitchen. A wildly divergent version of it is in A Traveling Man’s Cookery Book as Olive Oil Pie. I was in “someone else’s kitchen” and didn’t have brandy on hand, nor did I have butter. But I did have olive oil and a lemon and an orange picked up off the street. Citrus is literally free in San Diego in the right season: people leave out boxes of lemons, limes, and oranges with a note that says, please take!

I walk around a lot, so I see these boxes, and pick up a handful.

The Transparent Pie was as fascinating to read as to make. The ingredient list is atypically understandable, but typically weird—though not weird for the time. It calls for “the yolks of two eggs with one-third of a cup of butter and double the quantity of sugar…”. This is written like a novel, like a writer afraid to use the same word twice. How hard is it to say “one third cup butter” and “two-thirds cup sugar”?

For the flavoring to go along with the brandy I chose nutmeg. I used two tablespoons of brandy and ½ tsp of nutmeg, and I did so “to taste”. Egg yolk, butter, and sugar with brandy and nutmeg is unsurprisingly a very tasty filling. This probably makes enough filling for an 8-inch pie. I made half of a recipe and it barely filled a 6-inch pie. I baked it for 20 minutes at 400°; it was probably a minute or two overdone, so my guess would be 20 to 30 minutes for a full-size pie at 400°.

One of the interesting things about the pie recipes in Table and Kitchen is that a lot of the pies specifically say “No top crust” or “No upper crust”. All of the pies except the New England Pumpkin Pie and the Mince Pie either specify no top crust, a meringue top, or a top crust.

The Mince Pie only gives instructions on making the mincemeat, it says nothing about the crust.

The Apple Pie says specifically to use the upper crust, and then, after baking, it says, “Take from oven and quickly loosen upper from lower crust around edges and lay upper crust on another plate; scatter into pie two or three tablespoons sugar, a lump of butter and a little grated nutmeg. Replace upper crust quickly and put pie in oven again for five minutes.”

The Apple Slump has similar instructions, but the top crust is then replaced upside down, with some of the filling placed on top of it!

Making absolutely certain you know they only use natural ingredients.

…remove top crust, add sweetening, seasoning, and butter half the size of an egg; then remove part of the apple. Place top crust in an inverted position upon what remains, and the apple that has been taken out on top of that.

I’m sure either pie would be good, but that’s some serious work for what’s basically an apple crumble or cobbler.

For a book that otherwise is very typical of its era in not specifying practically anything, its attention to detail regarding the top crust is very atypical.

The Ginger Snaps in this book are a typical recipe. Typical for the time, but not for now. They are, of course, in the cake section because cookies are cakes.

They’re made by boiling molasses to a candy stage and then adding butter to melt. For the dry ingredients, I used 1 cup flour mixed with the ginger and baking powder. I then added another three cups to bring it to a smooth batter. I have a suspicion the recipe assumes that a little salt will be added, too. I’ll make it with ¼ teaspoon salt next time. I might also try to make it with slightly less or even a lot less flour—2 cups to 2-½ cups extra instead of three cups extra.

I flattened it with a wet fork, and baked at 375° for ten to twelve minutes, using a greased baking sheet.

These ginger snaps require patience. They get better every minute as they crisp up. Waiting several hours or even overnight will mean better texture and better flavor.

The Candied Pop-Corn was one of the more fascinating recipes that I’d highlighted to make. The way it’s written, it was potentially going to be like making cereal treats: melted sugar, and then popped corn stirred in. In fact, it’s more like the Grilled Almonds in the back of the 1893 Charlotte Cook Book: popcorn coated with a grainy sugar.

This recipe makes a lot of assumptions about what the reader knows. The instructions read “Boil until ready to candy”. What kind of candy? It doesn’t say. Before fudge? Before hard candy? Before caramelization? This is apparently a moderately popular recipe. Do a search on the term, and it brings up interpretations all over the map. Old-Fashioned Dessert Recipes calls it “Loose Popcorn Caramel Candy Pieces”. It’s very clearly the same recipe. Was Table and Kitchen a popular book, or did they both get the recipe from some other popular book? I suspect the latter.

The first time I made it I chose to interpret “until ready to candy” as just before hard ball stage, so I added the popcorn at 250°. This meant a sugary, grainy coating that was quite tasty. The next time I made it, I added the popcorn at 240° (I was going for 235° but lost track of the time). It produced the same result. I want to try both 230° now, and 270°, maybe even 290° to see if I can get some caramel flavor in it.

You’ll want to use a tall kettle. Otherwise, stirring the popcorn will result in hot sugar-coated popcorn occasionally overflowing as you stir.

Candied Popcorn

Servings: 8

Preparation Time: 1 hour

Table and Kitchen (PDF File, 15.3 MB)

Ingredients

- 1 tablespoon butter

- 3 tablespoons water

- 1 cup sugar

- 2-½ quarts popped popcorn

- 1 cup toasted cashews

Steps

- Stir butter, water, and sugar over low heat until sugar dissolves.

- Raise heat to medium and bring to a boil.

- Boil to about 240°.

- Stir in popcorn and cashews until evenly coated.

- Remove from heat.

- Continue stirring until cool.

One of the assumptions that I don’t really know is, what do they expect the popcorn itself to be like? The first time I made it, I used an air-popper, which I’m pretty sure was not in common use in 1916. My air-popped popcorn was just popcorn, no oil or salt. The second time, I used a standard whirly-popper, which means there was a small amount of oil with it. The former was fluffier and more sugar-flavored. The latter was less fluffy with more of the popcorn flavor coming through.

If you make the popcorn in the same pot ahead of time, or if you use an air-popper, this is a one-pot candied corn. It cools quickly once removed from heat, probably because popcorn is nowhere near dense enough to store large amounts of heat.

And it is screaming for some cinnamon sprinkled over it. I tried it that way the second time, and it is marvelous.

The eggnog recipe in Table and Kitchen is very close to the one in The Spice Cook Book from Avanelle Day and Lillie Stuckey; as well as the recipe in the more recent Ideals Christmas Treasury. It differs in that the latter versions contain cream. The Table and Kitchen version does not. Instead of a half quart of milk and a half quart of cream, it calls for a quart of milk. There’s also no mention of making the yolk/milk/alcohol part ahead of time and letting it sit overnight, as there is in The Spice Cook Book.

One other minor difference is that the Table and Kitchen recipe only calls for brandy, instead of a mix of brandy and rum or some other alcohol. The amounts, however, are the same. It’s clearly the same recipe, enduring across six decades.

| Table & Kitchen (1916) | Spice Cookbook (1964) | Ideals Christmas (1975) | Ideals Gourmet Christmas (1978) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egg Nog.—Six eggs well beaten (white and yolks separately), one quart milk, one-half cup sugar, one cup brandy, nutmeg. Stir yolks into milk, with the sugar first beaten with yolks. Add brandy, then whites of eggs. Whip well. | SOUTHERN EGGNOG 6 large eggs, separated ½ cup sugar (or to taste) 1 cup Bourbon or rye whisky, brandy (or other spirits to taste) ⅓ cup rum 2 cups milk 2 cups heavy cream, whipped Ground nutmeg Beat egg yolks until thick and lemon-colored. Gradually beat in sugar. Stir in desired spirits and rum. Cover and chill several hours or overnight. Just before serving, stir in milk. Fold in whipped cream and egg whites beaten until they stand in soft, stiff peaks. Serve in punch cups and garnish with ground nutmeg. YIELD: About 24 servings | Traditional Eggnog Makes 25 to 30 servings. 12 eggs, separated 1 cup sugar 1 quart milk 2 cups bourbon 1 cup Jamaica rum 1 quart whipping cream, whipped Nutmeg Beat egg yolks slightly. Gradually add sugar; beat until smooth. Pour in milk, bourbon, and rum; stir until well mixed. Beat egg whites until they form stiff peaks; fold egg whites and whipped cream into yolk mixture, gently but thoroughly. Serve cold with freshly grated nutmeg on top. | EGGNOG 10 eggs, separated ¾ c. sugar Dash salt 2 to 4 c. rum, brandy, bourbon, or rye (a combination of two is best) 1 qt. heavy cream, whipped Nutmeg Beat egg yolks until lemon-colored and thick. Beat in sugar and salt. Slowly add liquor, constantly beating with a wire whisk. When all liquor is whisked in, stir in cream. Beat egg whites until stiff and fold into eggnog. Chill for several hours before serving. Dust each serving with nutmeg. Makes 25 to 30 servings. |

Another interesting feature of the latest, 1978, version: it specifically says to add a dash of salt. This feeds my long-standing suspicion that older recipes left salt out, assuming that (a) the problem was too much salt, not too little, and (b) the cook would add any salt that was necessary automatically.

The lack of cream in the Table and Kitchen version makes for a far less fluffy drink; the only fluff comes from the beaten egg whites. It separates more easily, possibly because there is no cream keeping the egg whites in suspension. It’s tasty, and more drinkable on a general basis than the very Christmasy versions with whipped cream. And of course it’s a lot easier to make. You could easily whip it up (pun intended) in the morning or the evening for a family or group.

A recipe that almost certainly comes from an earlier book is the Cream Walnuts. A friend of mine has a very similar recipe in her great grandmother’s collection, “given her by friends and relatives when she left Virginia for Los Angeles (June 25, 1895)”.

A recipe from 1895 isn’t going to be from a 1916 collection. But it is very similar, indicating that both got it from the same source:

| Table and Kitchen (1916) | Leonora Wise Klingstein (ca. 1895) |

|---|---|

| Cream Walnuts.—Dissolve one pound powdered sugar in one-half cup water; boil five minutes and cool slowly, keeping constantly stirred; flavor when cold; if not stiff enough to handle, work in a little more sugar; roll into small balls, press half an English walnut on each side and drop into granulated sugar. | Cream Walnuts: 1 lb white sugar, ½ tcup of water. Boil until it threads. Flavor with vanilla. Then take from the fire and stir until white and creamy. Make the candy into small round cakes and press walnuts in the sides dropped in powdered sugar and lay aside to cool. |

Elsewhere in the book, my friend’s grandmother lists a “teacup” as “a scant ¾ cup”.

The least of the recipes I tried is probably the least partly because I do not know their assumptions.

The very first recipe in the Pickles and Catsups section where I got the Green Pepper Catsup from is Pickled Cauliflower. This sounded interesting to me. It’s flavored with “small red peppers”, vinegar, and “two tablespoons mustard”.

I assumed two things: this was not the kind of mustard we get in jars, because that’s usually called prepared mustard in recipes of this era. I used whole mustard seeds, because pickled vegetables that contain mustard usually have visible mustard seeds in them.

And I assumed that “small red peppers” would be hot peppers.

I can pretty much guarantee ground mustard would not be appropriate. This pickle had a very harsh flavor. Perhaps I should have used prepared mustard—it may be that the amount, two tablespoons, was a clue that contemporary readers would have picked up on. Or perhaps the amount was a typo and I should drop it down to two teaspoons instead of two tablespoons.

Beware those crafty Alum Baking Powder manufacturers!

It may also be that my tastes are not the tastes of the readers of this book. I see similar recipes that call for even more mustard. They also specifically mention mustard seed.

But it’s also likely that I should have used sweet peppers, thus adding a touch of sugar to the recipes and less harshness than red jalapeños.

There is also a “Relish” section in this book completely separate from the Pickles and Catsups. It contains one recipe: Welsh Rarebit. It’s clearly the standard Welsh Rarebit that is a sort of open-faced cheese sandwich. What is it doing on its own in the first place, as opposed to being in Sauces or one of the bread sections? Why is its section called “Relish”?

There are a lot more recipes under the Pickles and Catsups section that seem interesting, linguistically, as an example of what ingredients were available, and also just because they sound like they might be good.

One is a very modern chutney called “Indian Chetney”. “Chetney” appears not to be a typo, but the contemporary spelling, much as “gelatin” was once called “gelatine”.

While the Pickled Walnuts probably wouldn’t be to my taste, they’re still fascinating enough that I’d like to try them. But I don’t think I’ll ever have a source of fresh walnuts that I can “pick… when tender enough to pierce with a pin”.

The Green Cucumber Pickles look quite doable, flavored with spices as normal but with horseradish as the main pickle flavoring instead of dill.

The Sweet Cucumber Pickles are very simple compared to modern sweet pickles. No onions. No mustard or turmeric unless that would show up in a bag of “mixed spices”. I would assume that “mixed spices” means the same mix of allspice, cloves, and cinnamon that go into Green Cucumber Pickles, but of course I could easily be wrong. They could just as well be assuming that their contemporary readers would know which mixed spices go in which recipe.

Another cake that struck me is the Breakfast Fruit Cake on page 45. It ends the recipe with “As an accompaniment to the morning cup of coffee this cannot be beaten.” Sometimes this book seems so alien, and then a statement like that pops up that could have been said this morning. But it probably would not have been said about a fruit cake made with suet, currants, and moist sugar.

It might well have been said of a quick bread made partly with mashed potato, however.

Table and Kitchen contains a section of “Sustenance for the Sick”. As in other books of the era, this is mainly beef stocks of various kinds, and grains boiled in water. It also includes “Toast Water”, which was ubiquitous in these sections. It is pretty much what the title says: water strained through toast.

Toast Water.—Brown nicely, but do not burn, slices of bread, and pour upon them sufficient boiling water to cover. Let steep until cold, keeping bowl or dish containing toast closely covered. Strain off water and sweeten to taste, adding a piece of ice.

I decided that writing this post was a good time to try Toast Water. The recipe doesn’t say anything about how much toast to use, other than using the plural, and is moderately vague about how much water. I used two slices of toast, and probably a couple of cups of boiling water to cover. I should, I think, have used at least another cup. The bread soaked most of the water up, and even pressing the toast over the sieve left a lot of water in the toast.

As you can see in the photo I ended up with about a half of a tall glass of “toast water”. I tasted it, and then stirred two teaspoons of brown sugar in it, which may of course be the real medicine.

It wasn’t bad. It’s toast-flavored water, sweetened, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Far better would have been a glass of water and a slice of toast with sugar on it. It really is fascinating: how sick do you have to be to not be able to eat toast?

That said, if it were put before me, I’d drink it. I’m not being ironic when I say it’s “not bad”. It’s far from anything special, but it really isn’t bad.

Something I haven’t seen before is a very short subsection specifically “for miners or ranchmen.” It lists the utensils that a miner or ranchman should carry:

1 Iron Pot. 2 Saucepans. 1 Gridiron. 1 Frying-pan. Poor Man’s Jack for teasing.

I don’t know what a Poor Man’s Jack is or what teasing is. An Internet search just brings up people calling someone else a poor man’s Jack Benny… Jack Kerouac… Jack Black… and of course many Jacks I don’t recognize. When I add “teasing” I end up with a very obscure television series.

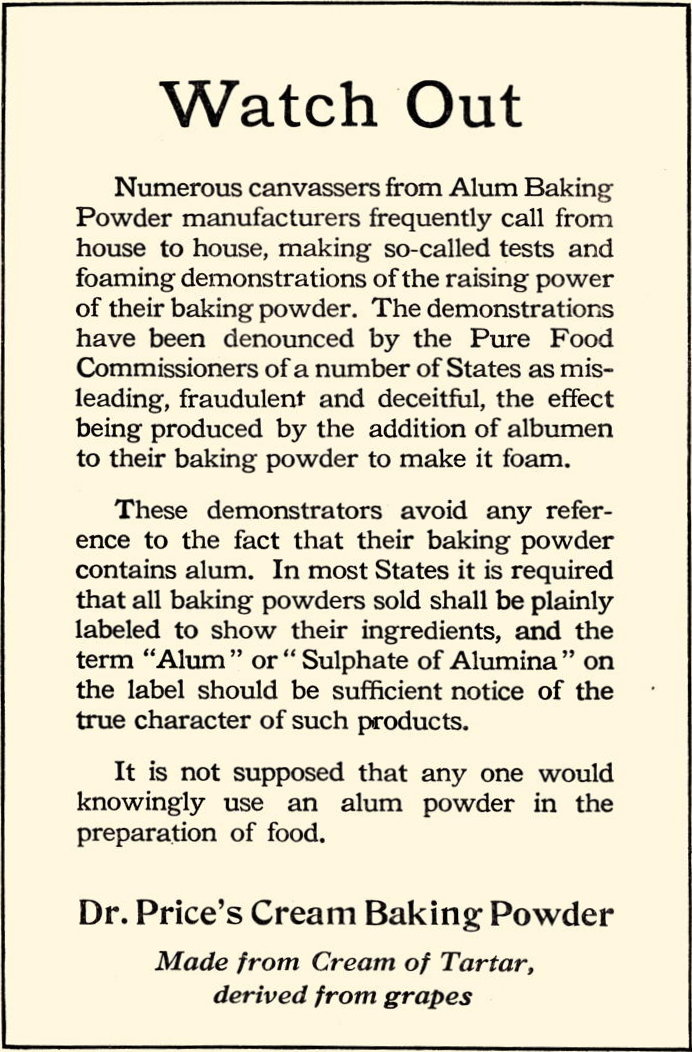

Another feature of this book is that it’s a marvelous entry in the great baking powder wars:

Watch Out

Numerous canvassers from Alum Baking Powder manufacturers frequently call from house to house, making so-called tests and foaming demonstrations of the raising power of their baking powder. The demonstrations have been denounced by the Pure Food Commissioners of a number of States as misleading, fraudulent and deceitful, the effect being produced by the addition of albumen to their baking powder to make it foam.

These demonstrators avoid any reference to the fact that their baking powder contains alum. In most States it is plainly required that all baking powders sold shall be plainly labeled to show their ingredients, and the term “Alum” or “Sulphate of Alumina” on the label should be sufficient notice of the true character of such products.

It is not supposed that any one would knowingly use an alum powder in the preparation of food.

“I am quite positive,” they quote a Prof. Vaughan of the University of Michigan later, “that the use of alum baking powder should be condemned.”

They’re not too happy about phosphate baking powders (made with bones) either. Dr. Price’s Cream Baking Powder is “Made from Cream of Tartar, derived from grapes.”

When I don’t have baking powder on hand, I use baking soda and cream of tartar to fake it. It’s not quite as powerful as double-acting baking powder, so I use more. If a baking powder is advertised as “double-acting”, it almost certainly contains some sort of alum.

I’m not aware that anyone uses albumen in their baking powders anymore. It’s derived from egg whites, so it may well have had more effect than this pamphlet implies. After all, if it causes foaming, it’s likely to contribute to at least some rise!

It’s also interesting that they felt the need to warn people not to knead when using baking powder instead of yeast. I suspect some of these helpful hints, like some of the recipes, are holdovers from much, much earlier.

Make the dough soft with cool sweet milk or water. DO NOT KNEAD. Dr. Price’s Cream Baking Powder is complete in itself and needs no other raising agent with it.

If you’re willing to put up with the odd-to-modern-eyes recipe format, this is a wonderful cookbook. I’ve scanned my copy, so that you can now download the PDF (PDF File, 15.3 MB) or buy a facsimile version in print.

And keep your eye on this page for a response by one of those Alum Baking Powder manufacturers…

In response to Vintage Cookbooks and Recipes: I have a couple of vintage cookbooks queued up to go online.

Download

- Table and Kitchen (PDF File, 15.3 MB)

- “A Practical Cook Book” from Dr. Price’s Cream Baking Powder. 1916.

- Table and Kitchen: A Practical Cook Book at Lulu storefront (paperback)

- “A compilation of approved cooking recipes carefully selected for the use of families and arranged for ready reference, supplemented by brief hints for the table and kitchen. Published by Royal Baking Powder Co., New York and Chicago, Manufacturers of Dr. Price’s Cream Baking Powder.”

miscellaneous

- The Biblyon Broadsheet

- Like adventurers of old you will delve into forgotten tombs where creatures of myth stalk the darkness. You will search uncharted wilderness for lost knowledge and hidden treasure. Where the hand-scrawled sign warns “beyond here lie dragons,” your stories begin.

- Review: Table and Kitchen: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- An entry into the Great Baking Powder Wars, and some fascinating old recipes.

- What is “White Moist Sugar”? at Seasoned Advice (Stack Exchange)

- “Looking online at a copy of Mrs Beetons Book of Household management and I came across a recipe that called for ‘White Moist Sugar’.”

Other Cookbooks

- Review: Ideals Christmas Cookbook Treasury: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- A collection of three previous Ideals Christmas cookbooks, I found the second and third books most compelling. The recipes are a strange combination of specificity and vagueness, but eggnog and the mince-cheese pie, at least, are excellent.

- Review: The Charlotte Cook Book: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This 1893 community cook book is a fascinating look at cooking and baking before much of the technology we now rely on, such as refrigeration.

- Tempt Them with Tastier Foods: Second Printing

- The second printing of Tempt Them with Tastier Foods contains several newly-discovered Eddie Doucette recipes, as well as an interview with the chef’s son, Eddie Doucette III.

- A Traveling Man’s Cookery Book

- A Traveling Man’s Cookery Book is a collection of recipes that I enjoy making while traveling, and in other people’s kitchens.

recipes

- Old Fashioned Popcorn Balls Recipe: Don Bell

- “These old fashioned popcorn balls recipes got plenty of use in our family. Dad would boil up some molasses or corn syrup while I popped the corn, and we would make some homemade treats to enjoy after the evening's farm chores were done.”

- A Vicennial Meal for the Sestercentennial

- In 1776 we were too busy to write commemorative cookbooks. But in 1796 “Amelia Simmons, American Orphan” published the first known American cookbook. It’s a celebration of American foods, American values, and American economies.

More baking powder

- Rumford Recipes Sliding Cookbooks

- One of the most interesting experiments in early twentieth century promotional baking pamphlets is this pair of sliding recipe cards from Rumford.

More food history

- Hot ovens: Bakers were once the slaves of time

- We have chained time in our kitchens. Our refrigerators stop time from destroying food, and our ovens lash it to the oars for baking. And we have forgotten that it was ever any other way.

- Using archives to guess cookbook years

- Many cookbooks, especially community cookbooks and often advertising pamphlets, leave off the year. Online newspaper and magazine archives can help to narrow down when the book was published.

- Padgett Sunday Supper Club Sestercentennial Cookery

- The Sestercentennial Cookery is a celebration of American home cooking for the 250th anniversary of America’s Declaration of Independence.

- Using search engines to guess cookbook years

- Many cookbooks, especially community cookbooks and often advertising pamphlets, leave off the year. Often, however, there are solid clues in the text that narrow down when the book was published, through simple online searches.

- Cookbook publication year estimates I have made

- When I acquire a cookbook without a publication or copyright year, I use the advertisements and contributors to make a stab at the likely year of publication. This page provides those guesses in case it helps you date your own books.

- 27 more pages with the topic food history, and other related pages