- Omni welcomes the eighties—Wednesday, December 17th, 2025

-

I’ve managed to acquire a few caches of early OMNI magazines, and recently read the February, March, and April 1980 issues. With a likely three-month lead time to publication, the essays and editorials in these issues would have been written in November or so through January. That is, at the very end of the seventies and the height of seventies malaise. President Carter was still president. While the Iranian hostage crisis was weighing on his presidency, there was as yet no obvious alternative to Carter in the Republican Party.

On January 1, 1980, Carter seemed more vulnerable from an opponent in his own party—Ted Kennedy—than from any Republican. President Reagan wouldn’t even start showing his strength in the Republican primaries until March. Like President Trump in 2016, candidacy would be treated as a joke until it wasn’t.

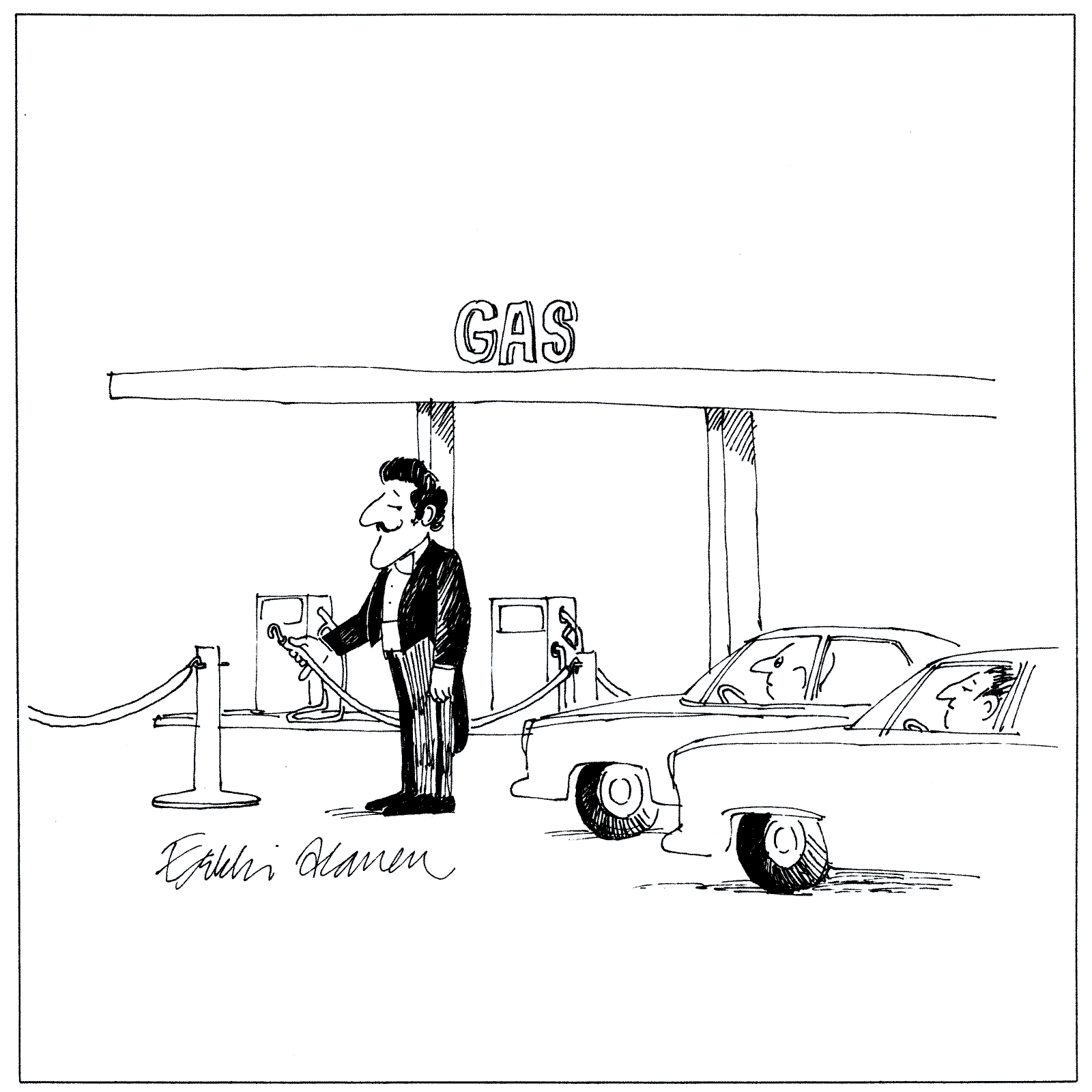

Emblematic of the era is a cartoon in the February issue showing a maitre’d controlling entry to a gas station. Under rationing and price controls, being able to both afford gas and have time to access it was becoming a class marker. That America was entering a period of decline was a widely spoken mantra in the beltway, and would continue to be until President Reagan’s new policies started taking effect in 1981 and 1982.

Most people in publishing and politics thought higher prices and higher unemployment—stagflation—was America’s inevitable future. They had no idea everything would change in just over one year when gasoline price controls would be rescinded and gasoline prices—along with prices for everything that relies on gasoline—would drop.

Tying into this seventies malaise was another surprise for me: a Thomas Szasz-like rant about the psychiatric industry that opened February’s “Continuum”1—and seeing by the signature at the end that it was in fact written by Szasz! Everybody wrote for Omni. As I recall from reading one or two of his books, Szasz had a lot of very good points—obscured by a near-complete rejection of potential physical causes for mental issues.

- A Plea to Preserve Meaningful Referrer Headers—Friday, December 12th, 2025

-

“Google is pushing a new stricter default for the Referrer-Policy header under the veil of privacy. Not only have they implemented this default in Chrome, they are also lobbying for everyone to configure it in their web servers… This article is a plea not to blindly follow suit by nailing shut the referrer header in every possible case, because that may do more harm than good.”

‘…it is an act of carpet-bombing the entire Internet with a measure that protects visitors only in a very limited set of situations, while in many other situations it only harms everyone in the long run. First the smaller websites because this new default increases their isolation, then the visitors who get jailed into a limited ecosystem of mainstream websites because the smaller websites die off or are hampered in their means to improve upon their content.

“I do not like this trend of the Web transitioning from what used to be a forum open to everyone, towards a collection of walled gardens, gated communities where everyone is utterly paranoid and sour, and expects to be exploited in every possible way if they don't sell their soul to a big tech company.”

Alexander Thomas: A Plea to Preserve Meaningful Referrer Headers at Dr. Lex’ Site (#)

- Farming hatred on social media—Wednesday, December 3rd, 2025

-

This is just a quick update on why “engagement algorithms” really mean farming anger: that is, what the financial stakes are that encourage artificially inflating engagement. Or at least, it started as a quick update. It quickly went off into the fields of effective advertising, and the ancient debate over eyeballs vs. sales.

Several social media sites reward people for delivering eyeballs—that is, for drawing in viewers and readers. Just as Facebook has discovered, one of the easiest ways to get eyeballs and to keep eyeballs is to encourage rage and hatred. The common term for this is “rage baiting”. It’s become such a common practice that it’s already progressed, language-wise, to a single-word contraction, “ragebaiting”.

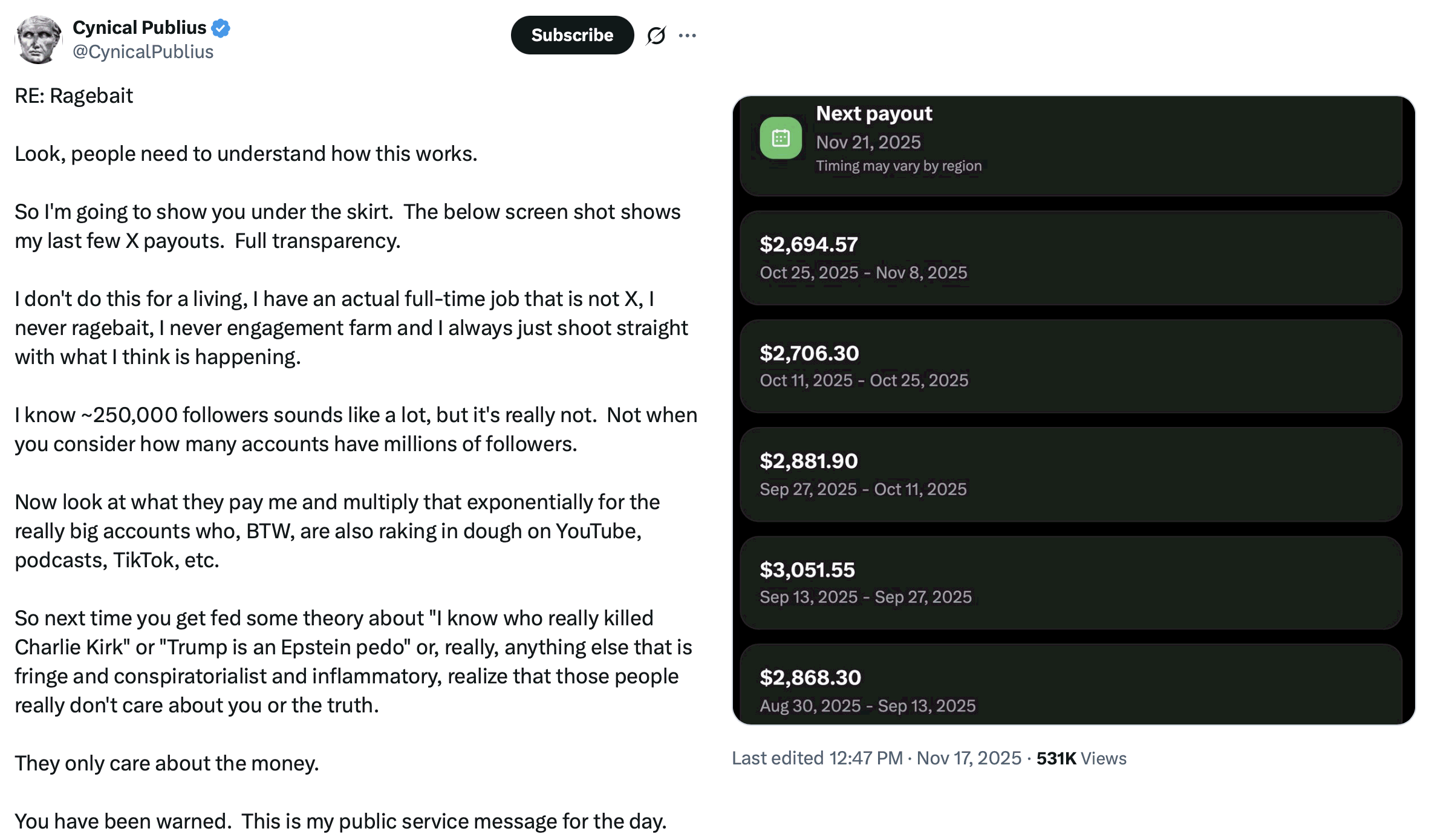

This is what Facebook’s algorithm is designed to encourage, and this example (from X, not Facebook) is the first concrete example I’ve been blessed to find describing how much money is involved. I couldn’t find anything like this when I wrote Facebook is designed to kill relationships.

When you look at these numbers, remember that they are basically affiliate payments. When affiliates are linked directly to sales, such payments run from a fraction of a percent to, at the very high end, four percent, which would mean multiplying by anywhere from twenty-five up to two hundred to get the actual gross profits involved. But social media posts aren’t generally tied directly to sales, only indirectly as delivering eyeballs of potential sales.

Much as the purpose of television shows on broadcast television was to draw in viewers to watch television ads, the purpose of posts on social media is to draw in readers to watch Internet ads. Very few of the viewers or the readers actually convert into buyers. So you’d have to multiply again by two and probably much more for the actual figures involved on X’s side of the ledger.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1927 Electric Refrigerator Menus & Recipes—Wednesday, October 1st, 2025

-

Also available in print.

This is the second of four addendums I’ve queued up to my three-parter revisiting the refrigerator revolution. That series was originally meant to cover 1928, 1942, and 1947; the latter just barely predated the modern near-universality of home refrigerator ownership. But as I delve deeper into the origins of the home refrigerator/freezer era, it is becoming almost literally the bottomless pit of fascinating fridge finds!

Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Frigidaire, 1928

- Cold Cooking, 1942

- Cold Cookery, 1947

- Kitchen-Proved, 1937

- General Electric, 1927 ⬅︎

- Refrigeration, 1926

There is always something more interesting just around the corner. While wandering an antique mall over the 2024 Thanksgiving holiday, I ran across this 1927 General Electric refrigerator manual (PDF File, 22.3 MB). It looked interesting, but (a) it was unpriced, and (b) it was missing at least one page. It also wasn’t the first printing, which meant I’d need to do some research anyway before buying it.

- Facebook is designed to kill relationships—Wednesday, September 24th, 2025

-

Facebook’s algorithm is designed to break up families and friendships. Creating strife is literally what its algorithms do. It’s what they mean by the extremely euphemistic term “engagement”. Friends don’t have to stay engaged. Family doesn’t have to stay engaged. Friends and family don’t have to keep in constant touch to remain friends and family. Both can go for months, even years, with no contact, get together, and it’s as if they’ve never been apart. We’ve all seen it. We’ve all experienced it. And that would be death for Facebook.

Facebook’s business model requires constant engagement. Their designers have decided that the easiest way to get constant engagement is with constant arguments. Only enemies must remain engaged. It’s what being an enemy means. Enemies are also easier to manipulate, because despite their constant engagement they rarely communicate. Enemies are easier to keep staring at the screen, alert for the next offense, ready to loose the next scathing attack.

It’s a lot like what Norbert Wiener• talked about in The Human Use of Human Beings.

…when there is communication without need for communication, merely so that someone may earn the social and intellectual prestige of becoming a priest of communication, the quality and communicative value of the message drop like a plummet. — Norbert Wiener (The human use of human beings: Cybernetics and Society)

How often have you seen an event in your main feed, only to realize that it happened yesterday, or even last week, but Facebook is only showing it to you now? And yet day after day Facebook sorts the arguments and the nasty memes right to the top? Events don’t create online engagement. They create offline engagement.

It’s easier to keep eyeballs on ads when everyone is an online enemy. Much harder when they’re an offline friend.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1937 Kitchen-Proved—Wednesday, September 3rd, 2025

-

Also available in print.

I’ve written so far about refrigerators in the twenties and refrigerators in the forties. While traveling over the Thanksgiving holiday last year I found an interesting Westinghouse book from 1937 or 1938. It provides a great opportunity to fill the gap and look at the thirties. If I’m right about the age, this book came out well after the end of Prohibition and well before the end of the Depression. Those who were paying attention to world affairs could see another Great War on the horizon, but for most people domestic concerns were a far greater priority.

Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Frigidaire, 1928

- Cold Cooking, 1942

- Cold Cookery, 1947

- Kitchen-Proved, 1937 ⬅︎

- General Electric, 1927

- Refrigeration, 1926

The Westinghouse Kitchen-Proved Refrigerator Book (PDF File, 11.6 MB)—also available in print—is undated but has a drawing inside that matches Westinghouse’s 1937 and early 1938 advertisements in magazines such as Good Housekeeping and The Saturday Evening Post. I suspect that the book is from 1937, because all of the ads from 1938 that feature this refrigerator and that include a month are from very early in the year.

- Refrigerator Revolution Reprinted: 1928 Frigidaire—Wednesday, June 11th, 2025

-

Frigidaire Recipes was the first entry in my Refrigerator Revolution: Revisited series. It came out before I started making reprints available. So I thought I’d take this as an opportunity to revisit it at the same time that I publish the Frigidaire Recipes reprint. Frigidaire Recipes (PDF File, 15.5 MB) is a wonderful book. It was, in fact, the inspiration for starting this series. While I’d already had the other books in the series, the 1928 Frigidaire Recipes was such an incredible peephole into the early years of the home refrigerator/freezer that I couldn’t stop thinking about what it meant about how home refrigerators changed home cooking.

- Refrigerator Revolution Revisited: 1947 Cold Cookery—Wednesday, February 19th, 2025

-

Like Montgomery Ward’s 1942 Cold Cooking, the Borg-Warner Corporation’s 1947 Norge Cold Cookery and Recipe Digest (PDF File, 10.2 MB) is marketed towards owners and potential owners of the company’s refrigerator. It’s not just a manual, but a cookbook full of reasons to use the product. While Borg-Warner was headquartered in Detroit, the Norge plant, according to this book, was across the state in Muskegon. Borg-Warner still exists; Norge long since hasn’t, although they seem to have continued in some form, probably in-name-only, up to 2006.

This is the third in a series about the first decades of the home refrigeration revolution. While I won’t be going past 1947 I will fill in some of the gaps between 1928 and 1947 with at least two more posts over the coming year. Here’s the series so far:

Revolution: Home Refrigeration

- Frigidaire, 1928

- Cold Cooking, 1942

- Cold Cookery, 1947 ⬅︎

- Kitchen-Proved, 1937

- General Electric, 1927

- Refrigeration, 1926

The first part of Cold Cookery extols the wonders of the Norge “Rollator” refrigerator. It describes how to maintain the appliance and outlines how to use it: which shelves to store which kinds of food on, how to adjust the dial for freezing times, that sort of thing. The freezer section of this 1947 refrigerator was still tiny, though it did have a separate set of freezer shelves for ice cubes and frozen desserts in addition to the main freezer box.

Mimsy Were the Borogoves

Mimsy Were the Technocrats: As long as we keep talking about it, it’s technology.