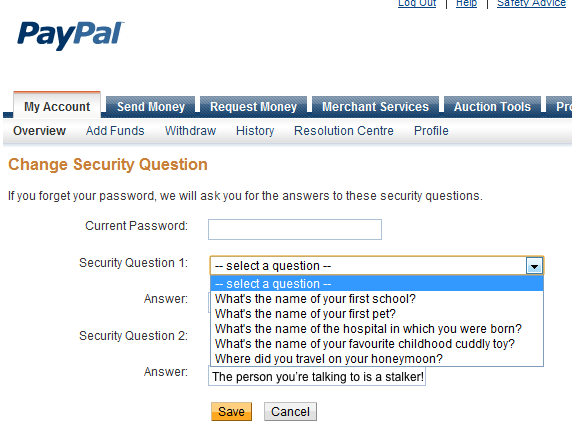

Insecurity Questions enable harassment and abuse

I bet they’d still let them in if the stalker called with a good sob story about being stalked.

I complain a lot about insecurity questions in other articles about organizations wanting to rely solely on them and not on human intelligence. For example, wanting banks to ignore that the person owning the account is listed as a woman but the voice is clearly a man’s.

The reason insecurity questions suck so much is that they don’t just enable hackers to persecute us. Most of us live in the serene knowledge that we are too inconsequential to matter to hackers, and even when hackers randomly choose one person to steal money from, we’re still just one in three hundred million in the United States, and one in seven billion in the world. The odds, we think, are in our favor.1

Insecurity questions suck because they enable easy hacking by precisely the people we do have to worry about: the abusive ex-boyfriend, the crazy ex-girlfriend with a penchant for boiling rabbits, the stalker, the shady brother-in-law who is always in debt. Insecurity questions rely on personal information that are already known by the people we most have to worry about. Even those answers that are not widely known among our acquaintances are easily knowable simply by engaging in normal conversation among our web of friends. And the people you have to worry about have access to the edges of your web of friends. All they have to do is innocently start talking about high school to someone they know went to high school with you, and they’ve got your high school. Your pet’s name probably has already been posted to Facebook and is easily accessible by a friend of a friend who is not your friend at all.

The entire reason for insecurity questions is so that someone who does not have your password can reset your password without having to talk to a human. The selling point is that they are for helping you when you don’t have your password. But they’re just as useful for anyone else who also doesn’t have your password.

Even among people who should know better, the issue is not taken seriously. Back in September 2008 when Governor Palin’s personal Yahoo account was hacked by some kid who merely researched Yahoo’s insecurity questions, I was very disappointed that even supposedly intelligent tech sites such as Ars Technica were more interested in posting hacked photos of her kids than they were in discussing the serious issues that insecurity questions pose.2

Any system that uses insecurity questions is vulnerable. This includes your bank, if your bank uses insecurity questions to let you bypass not knowing your account password.

Many times, the insecurity questions are asked and the answers chosen without any input from us. If you have ever had to answer questions about past addresses or organizations before accessing financial information, none of that information is secret. It comes from sources that can be mined by criminals just as it was mined by whatever computer program asked you the questions. These automated proof-of-identity systems are obscurely documented at best; even the Wikipedia page on out of wallet questions is just a stub. It’s a revealing stub, though:

Ideally, out of wallet information is easily recallable by a user but obscure to most other persons and difficult for them to uncover. Typical out of wallet questions a user may be asked include:

- What was the color of your first car?

- What is the name of the first school you attended?

- What is the name of the hospital you were born in?

Out of wallet questions appear to be nothing more than automated insecurity questions. Of those questions, two out of three are far from obscure. Your first school and the hospital you were born in are probably easily guessable by anyone who knows what town or neighborhood you grew up in. Even the color of your first car has a good chance of being on social media, especially if you are 26 or younger3.

Out of wallet questions address a long-standing issue in security: how do two sides of a transaction prove they are who they say they are, when at least one side doesn’t have any previous contact. When you go to a bank website, you can be fairly sure they are who they say they are because they’ve been vetted by other relatively trusted sources, such as the search engine you use or even their advertisements at their locations.4 But they have no idea who you are, if you are going through the process of identifying yourself online. They can’t compare the photo on your driver’s license, because you could easily have your browser give them a photo that matches the driver’s license—and the driver’s license itself is easily faked if all they’re using is a photocopy. The very fact that they don’t have an existing relationship with you means that you have never exchanged, in a secure setting, some personally-identifying piece of information. All they have are the public bits that anyone else can have.

The problem is that using only public information to verify identity is insane. This information is both knowable by precisely the people most of us have to worry about and is, literally, collected in databases that represent a single point of failure for hacking.

It’s a problem that will have to be solved as computers get more powerful and humans are more and more removed from the process of identifying valid vs. invalid applications. Or denied the ability to use common sense.

Because while humans often have information-processing capabilities exceeding that of software, when instructed by management—or finger nanny busybodies—to go easy on people who don’t have their password or even their insecurity questions this advantage is lost. It is far too easy to call a business, claim to have lost your password, and get the password reset with little more than on-the-fly insecurity questions.

The problem of secure identity authentication is a hard one. But it’s a lot harder if no one takes it seriously.

In response to Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say: Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.

It isn’t hard to imagine, however, a computer program designed to ferret out such information on social networks and government databases in order to access accounts en masse.

↑I can’t find the article now, but I do still have the responses from Julian Sanchez and Eric Bangeman defending their focus on the photos.

↑Facebook opened to anyone in 2006. If you turned 16 in 2006, you would be about 26 today.

↑I wonder if financial criminals have ever put fake sign-up flyers at ATMs?

↑

- 1Password

- “Mac OS X Password Manager with AutoFill that leverages the OS X Keychain and provides built-in support for most browsers.”

- 2016 Reality: Lazy Authentication Still the Norm: Brian Krebs at Krebs on Security

-

“The attacker had merely called in to PayPal’s customer support, pretended to be me and was able to reset my password by providing nothing more than the last four digits of my Social Security number and the last four numbers of an old credit card account.”

“The attacker had merely called in to PayPal’s customer support, pretended to be me and was able to reset my password by providing nothing more than the last four digits of my Social Security number and the last four numbers of an old credit card account.”

- Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

- Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.

- Insecurity questions on phones and at banks

- How important are the last four digits of your social security number? That and a high school yearbook can get a hacker your bank account.

- Out of wallet at Wikipedia

- “Such information is available to a database compiler but may not be readily available to criminals attempting to commit identity theft.”

- What is your favorite color?

- This is why I don’t like password recovery schemes that ask question which are public knowledge.

More identity theft

- Should Apple enable exes to access their ex-spouse’s iPad?

- Chris Matyszczyk wants Apple to just believe someone who says their spouse died, and give access to their iPad, then claims that this is how everything else, from house titles to bank accounts work. Unfortunately, he’s not far off there.

- Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

- Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.

More insecurity questions

- Security is hard, and 2FA is not the answer

- Is 2-factor authentication the magic bullet in security? Not unless we solve the real problem, which is that people always take the easy way out—and that includes service providers.

- Security questions will always be insecure

- Insecurity questions are insecure because their purpose is to allow access to someone who does not know the access credentials. This trait is shared by zero or one person who has forgotten their password, and an infinitude of people who never knew it in the first place—because they shouldn’t have access.

- Are insecurity questions designed to help hackers?

- Insecurity questions are being modified to make them easier to hack and harder to remember. It’s as if they’re designed to help hackers and frustrate forgetful account owners.

- Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

- Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.

- Mat Honan should read Mimsy

- “Because the last four numbers of your SSN are what businesses ask for, they are all that a criminal sometimes needs to use your cash or credit.”

- Two more pages with the topic insecurity questions, and other related pages

More vulnerable

- Money Changes Everything: Empowering the vicious

- Barbarism empowers the rich, the powerful, the vicious, the strong. Civilization empowers everyone else. Gun control and centralized economies, darlings of the progressive left, have empowered the vicious since the beginning of time. The beltway crowd prefers no competition from people free to barter, or free to defend themselves.

- Handmaid’s Tale experiences backlash over handling of religion

- Fans of Margaret Atwood’s new television show turn against the series after revelations the story is a metaphor for Islam’s treatment of women.

- But the rhetoric’s so much better here under the tragedy!

- Want to stop domestic terrorism? Take seriously those who say they want to kill. Want to stop the oppression of women and the gay community? Take seriously those who say they want to literally enslave women and kill gays.

- Allow men to impersonate exes, transgender activists say

- Some transgender activists want banks to reduce the security on bank accounts, enabling abusive exes to access their victims’ bank accounts.