Recent purchases:

- My Year in Books: 2025—Wednesday, January 14th, 2026

-

The book year for me began in earnest over Valentine’s Day travel in San Diego—and on the way to it. Driving through west Texas and El Paso I listened to Mike Rowe’s interview with Nikki Stratton about her grandfather, Donald Stratton, and the book he wrote with Ken Gire about being on the USS Arizona during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

I’ve long been aware of a Stratton on board the Arizona. While I’m pretty sure we’re not related it did of course interest me. So, when I happened to see Don Stratton’s All the Gallant Men a few hours later at Coas Books in Las Cruces, I couldn’t resist buying it.

To Donald Stratton, the attack on Pearl Harbor mirrored the September 11 attacks, and he lamented that the lessons we learned on December 7 are being forgotten. One of those lessons is a question: “Am I worth dying for?”

To paraphrase Kevin Smith, the Arizona wasn’t even supposed to be there that day. It had been involved in an accident and stayed in place for minor repairs. It accounted for “nearly half of all the Americans who died that day”.

We were so young, those of us who enlisted—eighteen, nineteen, twenty years old… If we were not quite men on December 6, by midmorning of the 7th we were.

It’s an incredible story. He covers not just the morning of December 7, but also his recuperation back home in mid-America and his return to the United States Navy to finish out the war.

Though I may have left Pearl Harbor on a stretcher, I had returned on a Destroyer. I had recovered my strength, as had my country.

While in San Diego I picked up a book at the big monthly University Heights Public Library sale that was to occupy my time on and off literally up to the end of the year. I began reading Giuseppe Ungaretti’s Il Dolore in March while traveling in and around Barcelona. I finished it this morning as I write this post, New Year’s Eve, 2025, making it my “last review of the year” according to Goodreads.

- Astro City: Tarnished Heroes, Local Villains—Wednesday, August 20th, 2025

-

Mary Marvel demonstrates the joy of flight. This seems to be what Busiek was initially striving for, but gave up on.

Addressing the weird impossibilities in superheroes and superhero worlds deconstructively isn’t necessarily a bad idea, and some of the stories are in fact passably decent, with even better characterization than you normally get from deconstructive stories. Busiek’s a good writer. But the deconstructive stories he ended up writing were far easier than the reconstruction of the superhero that he set out to do. That failure is more disappointing than the stories are enjoyable.

Probably the worst and best example of this comes in Local Heroes, the fifth book in the series. The third book, Family Album, provided a brief respite of sorts. It took on a topic that superhero comics rarely do: family. On the other hand, it did the same for the family that the series had so far done to being a superhero or just living in a superhero world: it showed the insurmountable problems such a world creates for normal family life, foreshadowing the problems of justice in Local Heroes. In Busiek’s telling, even a golden-age world of superheroes is necessarily a world of existential loss.

The frame in Family Album followed a normal family moving to Astro City—and getting caught in the family dynamics of the gods themselves. The main story involved Jack-in-the-Box attempting to maintain a family life in a world not just of superheroes but of, again, time-spanning superheroics. It’s up-front about the fears of fatherhood, of what happens to your children when you’re gone, of how children embody multiple potentials. In a superhero world those infinite potentials are real, and they bring infinite pain.

The Junkman story in Family Album follows an old man who is unable to share his accomplishments: the Junkman had no family. In a normal world, this would be the story. In a superhero world, he creates a complicated scheme to ensure that someone will appreciate his life. A world of superheroes creates loss, and in a world of superheroes, loss creates more loss. The pebble rolls downhill and takes out a city.

Tarnished Angel is Jim Rockford meets Marvel. But unlike Rockford, Busiek’s protagonist really is a loser. He never amounts to anything, not even at the end. I’m sure that’s the point, and it was moderately enjoyable reading once and then again now as I’m going through my old comics. But even at its darkest, the explicit point of Astro City was the joy of it, like that old drawing of Mary Marvel flying into the sky with a heavenly smile. Not only does Tarnished Angel not have that joy, it doesn’t have anything to replace it with, either.

- Astro City: Hope to Hopeless in the Big City—Wednesday, July 30th, 2025

-

In his first Astro City collection, Life in the Big City, Kurt Busiek set himself a very noble goal:

The superhero has been dissected, analyzed and debunked, his irrationalities held up to the light… to show them for the unworkable Rube Goldberg machines they are… it’s almost become impossible to present a superhero who does what he does without being emotionally unstable, incapable of dealing with reality… We’ve been taking apart the superhero for ten years or more; it’s time to put it back together and wind it up, time to take it out on the road and floor it, see what it’ll do.

Having this goal in mind—unstated in the uncollected single issues—made the debut of Astro City a real breath of fresh air in superhero comics. I remember avidly searching out each issue and then each collection as Busiek moved from Superman to Batman to Marvel, each with a new world of wonderful stories combining the charm of the old-school with the art and storytelling of the new.

Unfortunately, Busiek found it very hard to transcend his era; his desire to “floor it” never exceeded deconstruction’s 55 mph limits. That makes even the best of these books not stand up well to re-readings. But what Busiek wanted to do was so necessary that it took me, at least, a long time after I stopped looking for the collections to remove them from my want list. I wanted to believe long after I lost faith.

Even the first collection, a take on Superman, amounts to mostly deconstruction rather than reconstruction. At best it’s deconstruction from a different angle. Few writers have really grokked Superman. Outside of Maggin! and Morrison• even those writers who don’t prefer a Moore-like destructor of worlds still don’t understand the genuine balanced goodness underlying Superman, his upbringing, and the Metropolis he inhabits.

On the surface, that Busiek isn’t up to the level of a Maggin! or Morrison is forgivable. But he needed at least to try to reach those stars in order to achieve his noble goals. Instead, rather than a Superman so powerful he cannot but fall to the temptations of power, Busiek’s Samaritan is so good he cannot possibly balance his life as a hero and reporter. Asa Martin works at a newspaper just as Clark Kent does. But Martin is not a reporter. He’s a fact checker, isolated in his private, locked office, never interacting in the newsroom as Kent so famously did. There is no Lois Lane, no Jimmy Olsen, no Steve Lombard for Asa Martin.

- My Year in Books: 2024—Wednesday, January 8th, 2025

-

The year started with an amazing collection of books from a trip to San Diego. I have so many books in my to-read pile that I don’t travel for book sales anymore, but if a book sale happens to be where I’m traveling… In San Diego I hit the La Playa Bookstore remodeling sale and the University Heights Library Sale. I also visited Verbatim Books, the Mission Hills Library Store, and Grace’s Book Nook. And of course I stopped at Coas in Las Cruces on the way out.

For a blackjack total of 21 books. Thongor in the City of Magicians, from Coas, kept me in reading material through New Mexico and Arizona. Post Captain, The John Wayne Code, Gracie: A Love Story, Lights Out, The Pope Benedict XVI Reader, Stella Fregelius, In Trump Time, Cyrano de Bergerac…

“This plus your regular class load should turn your brain to tapioca in less than a month.”

I’ll have more to say about tapioca when I get to 2024’s Year in Food.

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands—Wednesday, May 22nd, 2024

-

“Last night, I woke up frightened o’ dying… I felt as if everythin’ was lost.”

Why should we care what a comic book writer with aspirations to wizardry has to say about superpowered manipulative bastards? The short answer is, we shouldn’t. But Moore is a very smart and insightful writer. All of the things he has his V and V-adjacent characters do are things that twentieth and twenty-first politicians would like to do. Does it make it okay that unlike everyone else’s eugenics programs throughout the last century and a half, Miracle Man’s is likely to be successful at its goal of improving the human race? Does it matter if Veidt’s murder of millions actually does usher in world peace?

All powerful modern politicians and many powerful modern billionaires claim that turning over individual freedom to the state or to their product will improve lives. Are they right? Does it even matter if they’re right?

Even if modern technology literally saves us, as it does Cyborg in Twilight, is it right to give so much of our lives over to it?

FiVe Faces of Alan Moore’s SaVior

- The First Face of V: A Crucible of Fire

- The Second Face of V: The Twilight of Man

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You

- The Full Face of V: In Your Hands ⬅︎

- The Rambling Face of V: V for Von Neumann

- The Fifth Face of V: I Have Saved You—Wednesday, May 8th, 2024

-

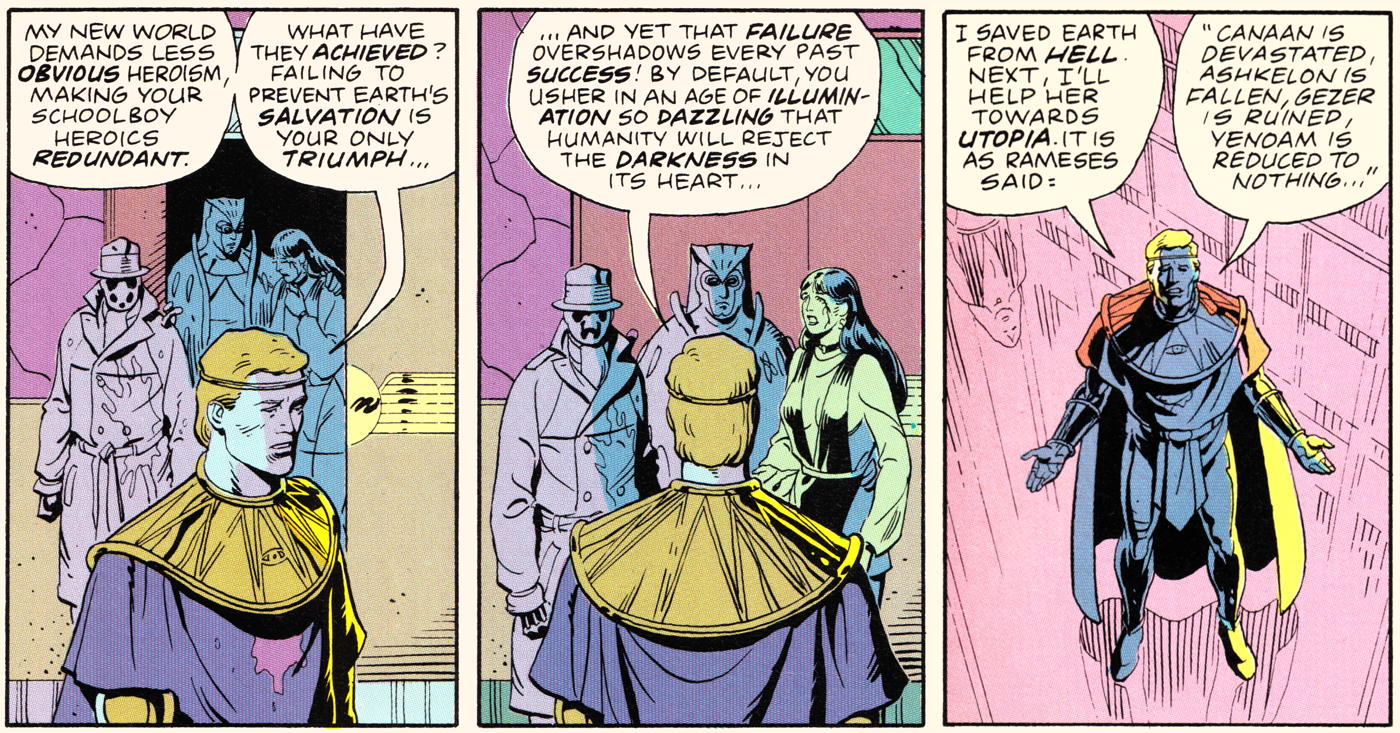

Veidt may believe mankind will reject the “darkness in its heart” and that his destruction of “half of New York” is a forgettable step to his new utopia…

While From Hell and Promethea are V-adjacent, Miracleman isn’t a V tale at all. Miracleman isn’t devious. He doesn’t scheme to supplant humanity; rather, the responsibility is thrust upon him, and he is equal to the task. Miracleman and From Hell are two extreme ends of the graph of perfection. Miracleman is perfect; William Withey Gull is seriously damaged.

Where a stroke left Gull unable to reason and prone to illusions of ascendancy, Michael Moran has successfully ascended, in an origin similar to V’s. Like V, Miracleman escaped and destroyed the medical experimentation camp that created him.1 Unlike V, however, Miracleman really is perfect.2 His tyranny is as perfect a tyranny as man or god could hope to devise. It’s rule by the strong, but the strong provide for the weak, far more than Norsefire in V for Vendetta did. It’s a return to barbarism—to rule by force and whim rather than democracy and law—but it’s a barbarism of plentiful food, plentiful energy, plentiful freedom, and good health.

They have defeated space, and are on the verge of defeating time. And yet:

In all the history of Earth, there’s never been a heaven; never been a house of gods, that was not built on human bones.3

We could easily see Evey or Veidt cradling the dismembered corpse of humanity, crying “I have saved you” as Gull does to Marie Kelly at the end of From Hell4 or as Miracleman does, wordlessly, to young Johnny Bates after crushing the boy’s head.

“I have saved you. Do you understand that? I have made you safe from time.”

- The Fourth Face of V: Science ascends, Man gives way—Wednesday, April 24th, 2024

-

Promethea directly invokes a connection with Prometheus and stealing fire from the gods. While the Five Swell Guys muck about ineffectually with technology.

If there’s one commonality between Moore’s variant worlds, it is a moral foundation weakened to nonexistence. And if there’s any commonality as to why, it is because technological progress has enervated us. If his appendix to From Hell can be trusted, Moore’s vision of technological progress is a terrifying one. From Hell was set in a squalid pre-technological Eden more alive than the modern world it preceded.

Scientific advances that moved away from the human—such as using dogs to solve crimes—were ridiculed. Gull’s vision of the future showed him a technological Olympus that had reduced mankind to emotional amputees.

In V for Vendetta, as in Orwell’s 1984•, technology exists only for the government to stifle the masses. Promethea gives us a near-future where our marvelous utopia is even more heavenly—and even more enervating and stifling—than what Gull foresaw in From Hell. The Internet exists but has little effect on people’s lives except as a barely mobile telephone/post office. Promethea’s only nods to modernity are the meme-like Weeping Gorilla billboards, a corporate top-down messaging system more like Wells’s Babble Machines in The Sleeper Awakes than modern viral memes. In the world of Promethea Sophie doesn’t even consider using the Internet for research. She goes to the library to find out where Promethea came from.

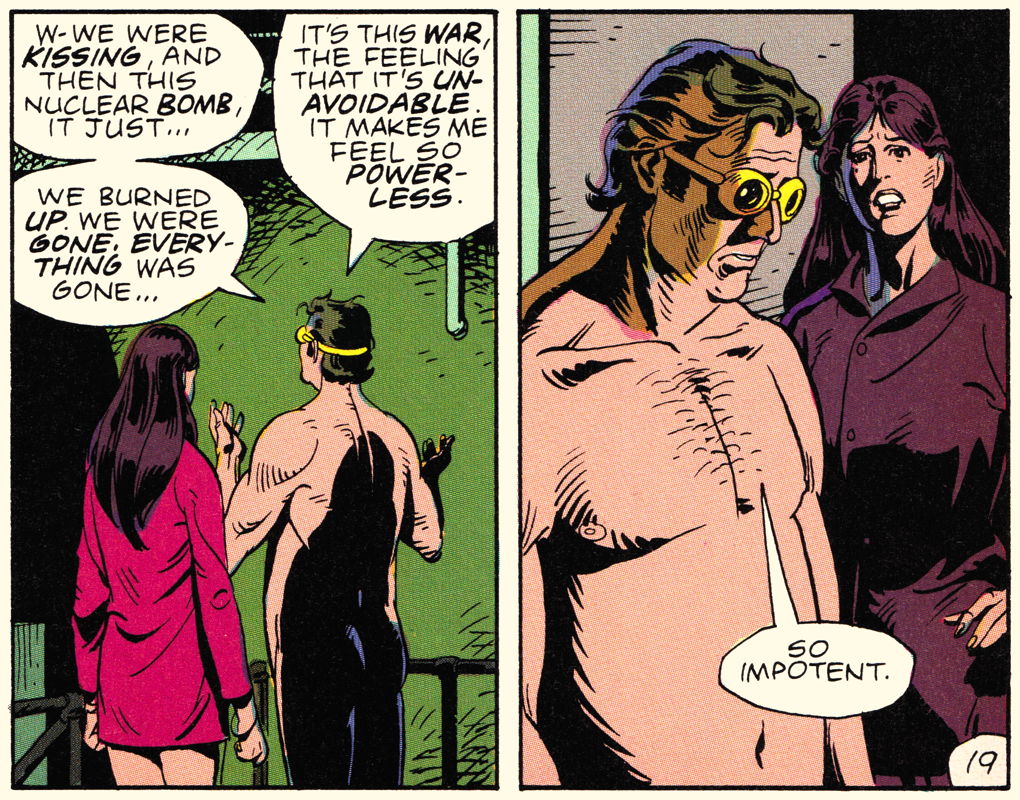

Superheroes in Promethea are Science Heroes. The main science heroes are the very impotent Five Swell Guys. They have no idea how to classify Promethea, because they can only see her as “some kind of science heroine”.1 They are blind to the mysticism inherent in her.

Promethea highlights both the best and worst of Moore. It’s a sprawling epic filled with emotive personal moments, interspersed with interminable lectures about the nature of illusion and reality, and why a world that most people find perfectly acceptable requires revolution.

- The Third Face of V: The Freedom to Starve—Wednesday, April 10th, 2024

-

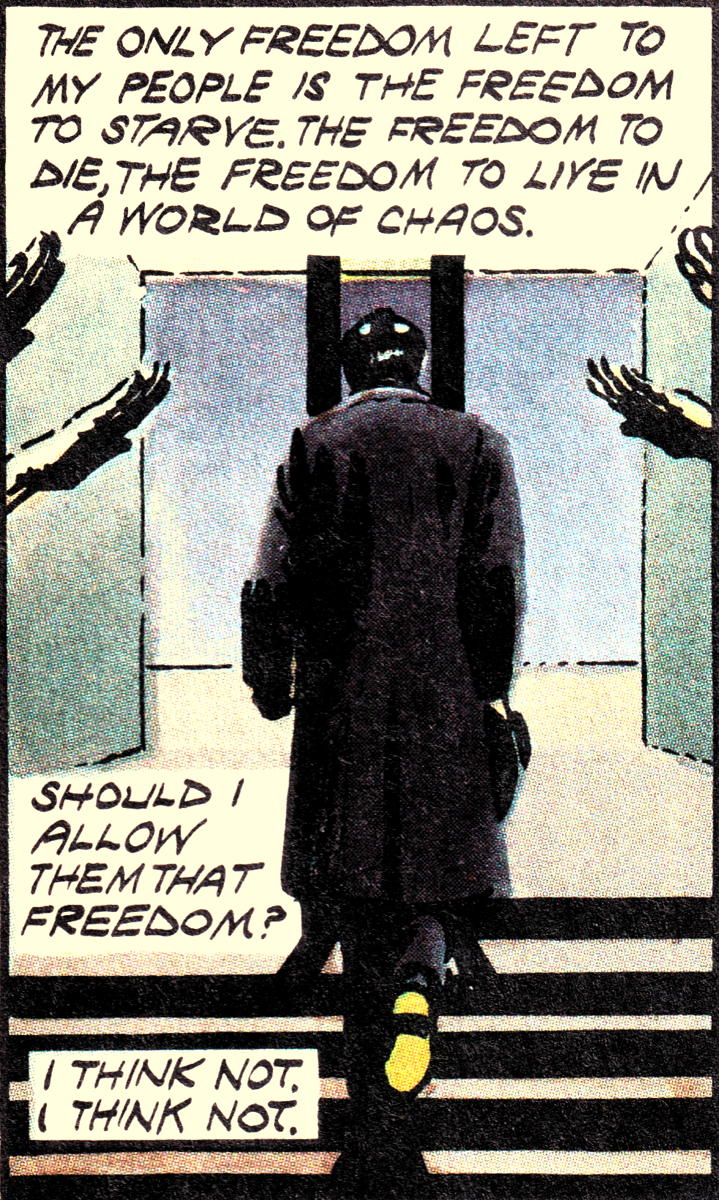

“The only freedom left to my people is the freedom to get sick. Should I allow them that freedom?”

Is V in V for Vendetta good or evil? Do his ends justify his means? Are his ends even desirable? What Norsefire did to bring peace to England and to bring food to the people was horrific. But what V does to Evey is also horrific, on a personal level, and what V does to the people of England is horrific on a mass level. V, Veidt, and Constantine have a vision, but their methods are as much Jack the Ripper as William Withey Gull’s was in the pursuit of his own vision, and may well share nearly as much of Gull’s madness.

We have little sense of how much of what V says is true, and how much he made up to justify his torture of Evey and England. His motto is By the power of truth, I, while living, have conquered the universe. V, however, uses everything but the truth in his relationship with Evey, creating a semi-imaginary prison and fake death sentence to indoctrinate her into his own version of anarchy.

Evey even acknowledges the technique: she can’t know if the toilet paper memoirs she read when confined are real. But by then she’s internalized V’s worldview enough that it doesn’t matter. Moore leaves no ambiguity here for the reader: she has been brainwashed, using standard brainwashing techniques.

The Norsefire of V for Vendetta succeeded because people were dying of starvation and failing infrastructure. Under Norsefire the people of England didn’t have the plenty available to the typical eighties comic book reader, but neither were they dying of starvation. By the end of the book, what has V given the people of England? Starvation and a broken infrastructure. And we don’t even know if England is free from tyranny!

The only freedom left to my people is the freedom to starve. The freedom to die, the freedom to live in a world of chaos. Should I allow them that freedom? I think not.—Adam Susan

As presented in V for Vendetta, this could only be a totalitarian thought. But think of what’s happened over the last four years. Should we have allowed people the freedom to catch COVID? Or should we have let them live in the chaos of freedom of movement, freedom of association, and the choice of how, and whether, to protect themselves against sickness?

If asked in the context of the COVID restrictions of 2020 and the vaccine requirements later, a lot of people today agree with Adam Susan’s conclusion. “I think not.”