My Year in Books: 2022

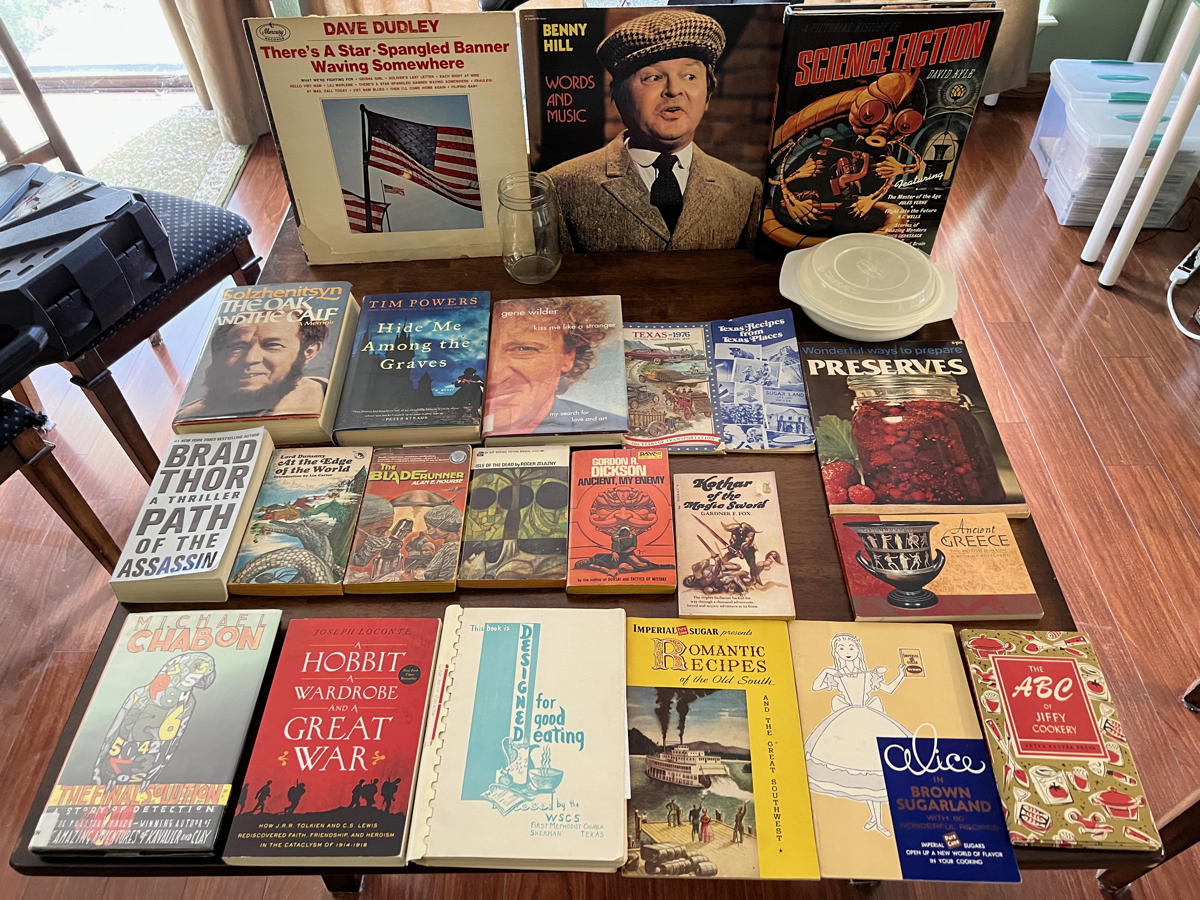

Not including the cookbooks (I’ll have more about 2022 in Food in a later post), my year in books began with Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience, a fascinating collection of essays about the dawn of civilized war, and ended with Mack Reynolds’s Code Duello, a very strange letdown about frivolous fighting on far planets. In fact, two books I read in December were letdowns. I see Mack Reynolds all over in the old paperbacks section of used bookstores, and somehow confused him with a writer of a spy or thriller series of some kind. No idea who, now.

The other disappointing December book was a Dorothy Parker collection; I’d never read her before, and of course you keep hearing about her as a very witty writer. I found her mostly repetitive and condescending.

Tastes vary.

My penultimate book was a re-read: the Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons comic book, Watchmen. I’ve been rereading a handful of Alan Moore’s best works lately. Both Promethea and V for Vendetta. They’re connected by Moore’s fascination with superhumans taking it upon themselves to save humanity from themselves, whether humanity wants it or not.

Sadly, minus the superhuman part that’s always an important topic. Which makes me glad to see that Watchmen is also the most-shelved book I read this year.

Alan Moore’s are not the only comics I chose to re-read in 2022. I also reread The Essential Calvin and Hobbes. I still remember the first time I read this book, just out of college, when one of my roommates had left it lying around. He probably regretted that, because I could not stop laughing out loud in the middle of the night, nor could I put it down. Calvin’s world is a world that doesn’t exist, and one I’ve never lived in, a suburban countryside where six-year-olds can wander downtown alone with their teddy bear (or, in this case, tiger), but it is hilarious despite my complete lack of reference points. Watterson riffs on the essential absurdity of man’s imagination, and it isn’t just Calvin’s imagination. Calvin’s father is quite the storyteller, too.

My antepenultimate fiction read this year—and I mention it not just because it lets me use “antepenultimate” in a sentence but because it’s very good—was Tim Powers’s Hide Me Among the Graves. It’s a vampire book… sort of. If you’re familiar with Tim Powers, you know his vampires are going to be involved somehow with the secret history of historical personages, and this time it’s the artistic Rossetti family and people associated with Lord Byron. His vampires are creepy, weird, ghostly, and very compelling.

The longest book by number of pages was Harry V. Jaffa’s amazing Lincoln history A New Birth of Freedom. It ties in well, believe it or not, to Moore’s comic books.

The myth that those who govern are, or may be, of a nature superior to those they govern is the root of tyranny.

Jaffa wasn’t arguing that President Lincoln was not a superior intellect, but against the system of an elite master-race that Lincoln was fighting against. Lincoln was very much the outspoken outsider, hated by the beltway class of his time because he told the truth about things the beltway class had chosen to ignore: the evils of slavery and how obvious those evils were even to those who practiced it. Like other outspoken outsiders, he was sabotaged by the then-nascent administrative bureaucracy, both before he entered DC and during his presidency.

It is impossible to grasp the full measure of the difficulties Lincoln faced without grasping the extent to which Buchanan had effectively cooperated with the Southern disunionists.

Lincoln had to fight the deep state every step of the way; President Buchanan and the Democrats would have preferred to allow slavery to spread throughout the nation.

“That human beings belong to God,” wrote Jaffa, “has as its correlate that they do not belong to anyone else.” Rulers, and those who wish to rule, always seem to find that humans belong to the state.

The evils of slavery is also one of the themes in one of the greatest adventure series of the twentieth century. In The Gods of Mars/The Warlord of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs crafted a tale of a master race that sounds a lot like the Southern Democrats of Lincoln’s time:

“It is an honor to a lesser creature to be a slave among us.”

Like Lincoln’s enemies, John Carter’s enemies compare the management of their “lesser races” to the domestication of animals. Carter constantly boggles at and opposes the unthinking prejudices of the various rulers of Mars. There are, in his view, no lesser and greater races, only lesser and greater individuals. And those who would enslave their fellow men are lesser individuals.

One of the evils of potential dictators and slavers is how easily they twist science to justify their rulership of others. Decades after Lincoln, the idea that some men are more evolved than others retained a powerful hold on those who wish to rule. It still does, which is why Lincoln—and Moore—are so important.

And G.K. Chesterton. The affinity of the ruling class to slavery was one of the themes in his The Everlasting Man. Chesterton argued that “the more we really look at man as an animal, the less he will look like one.” That there is something far more different between man and the animals than there is between different kinds of animals. Without that perspective, which is an essential part of Christianity, it is very easy for rulers to succumb to the urge to see the ruled as less evolved than the rulers. To see them as animals, as a herd to be managed.

As belonging not to God, but to the state.

The denigration of man as just another animal is also the trivialization of evil as just another human failing. Chesterton argued for the existence of an Evil outside of man, that has been stalking and tempting and diverting us since we first stepped above the animal. And also that there is an ultimate Good as well, “something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear”.

It is necessary that we recognize the existence of both Evil and Good if we are to fight Evil. This was not a popular opinion when Chesterton wrote it. It is not a popular opinion today. But during the horrors of World War 2 it was harder to deny. Chesterton saw those horrors coming. Not their form, but that if we persisted in denying the existence of evil, the horror of it would be overwhelming.

Eugene B. Sledge described some of those horrors in With the Old Breed. He was a soldier in the Pacific campaign in World War II, and experienced the dehumanization that afflicts those who have to fight that totalitarian evil. To say that the numbers become numbing is cliché, and it doesn’t even begin to approach the true horror. That millions would have died defeating Japan without the atomic bomb is one of those numbers; it’s difficult to grasp, sitting here at a computer three quarters of a century later.

But Sledge and his comrades, veterans of places like Peleliu and Okinawa, comprehended those numbers. They were who the numbers represented.

Another cliché is to say that World War II was just an extension of World War I. In A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War, Joseph Loconte argues that World War I devastated not just people and lands, but an entire philosophy—a religion—that had begun to arise among the elite, that…

…Western civilization was marching inexorably forward, that humanity itself was maturing, evolving, advancing—that new vistas of political, cultural, and spiritual achievement were within reach… Rational Europeans would no longer indulge in the kind of extended and brutal campaigns of previous years. The days of religious wars, the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War—these were relics of a bygone era. Short, tidy wars would be the norm, with healthy economic and political outcomes.

This Myth of Progress was part of the progressive Darwinist politics of the pre-Great War world, and it would take a very dark turn after the War proved it wrong.

The perverse relationship between technology, science, and power became a defining reality of the postwar years. Eugenics, communism, fascism, Nazism: these were the revolutions and ideologies that arose in the exhaustion of the democracies of Europe, all in the name of advancing the human race. All began by promising liberation from oppression; all became instruments of totalitarian control.

My father is a fan of mysteries of all kinds, which means that when I was young I read a lot of Agatha Christie. But since leaving home I haven’t reach much at all. So when I saw The Mysterious Affair at Styles and N or M? at the Temple Library Book Sale, I decided to pick them up. What I didn’t know was that this would tie into my year-in-books war theme. Mysterious Affair takes place at the start of World War I. N or M? takes place at the start of World War II. They’re good stories on their own, but it was fascinating reading them back to back.

In N or M? especially, Christie captured a feeling of vulnerability among the English, that there were spies everywhere and no one could be trusted, not even—or especially—among England’s intelligence services. But Christie also captured the feeling of horror that their government had been captured by progressives who were willing to do anything to achieve the perfection of man.

“You would be surprised if you knew how many there are in this country, as in others, who have sympathy with and belief in our aims. Among us all we will create a new Europe—a Europe of peace and progress.

There’s another side to treating your fellow man like an animal, and that’s treating him like a computer. This, also, was one of the sins of Moore’s villain in Watchmen. Ozymandias thought he could reprogram men to be more like him; he thought he could reprogram society to match his ideal. And he thought that a new and better world was worth the death of millions.

Michael Chabon addressed that by way of a Sherlock Holmes homage, The Final Solution. What happens when the most logical of men is faced with the most illogical of villains? The other side of the big lie is the incomprehensibility of the big goal. That there are people in power who wish to reprogram society regardless of the cost in lives—who in fact seem to turn murder into a virtue—is difficult to grasp. That’s how an Ozymandias, or a National Socialist Germany, or a Soviet Union, or a Communist China, can succeed in killing so many. It literally boggles the mind, especially the logical one.

Anyone who cries out against the coming horror, such as a Lincoln, a Chesterton, or a Rorschach, is called a warmonger, a conspiracy theorist. They are shunned by all right-thinking people, and their warnings ignored until Death has already ridden its pale horse into the world.

And in that vein, the shortest book I read this year wasn’t a book at all, but one of the most important texts in the history of computers—and especially in the history of how computers and people should and will interact. Vannevar Bush’s As We May Think defined the coming computer and Internet revolution before we even had a language to describe it.

Bush was one of a trio of influential computer scientists, though most of them wouldn’t have called themselves that, that I read in 2021 and 2022 for my Our Cybernetic Future series. I’ll have the exciting conclusion up in a few weeks, but Norbert Wiener’s The Human Use of Human Beings is a must-read. It’s actually a re-read for me. I bought this book from a library street sale as a teen, when I was far too young to understand the import.

Wiener’s warning that entropy means there is no guarantee of any sort of upward curve of history is very similar to Chesterton’s warning that treating our progress from barbarism to civilization as a story of Darwinian evolution ignores the essential fact that civilization is not guaranteed to increase. And that losing our religion is not a sign of civilization, but rather a surrender to entropy. Chesterton didn’t call it entropy, but it is what he meant:

The Christian creed is above all things the philosophy of shapes and the enemy of shapelessness.

Of course, few people read Chesterton, Lewis, and the classics they relied on, in modern education. That was part of Allan Bloom’s warning in The Closing of the American Mind. “Deprived of literary guidance,” Bloom wrote, students “no longer have any image of a perfect soul, and hence do not long to have one. They do not even imagine that there is such a thing.”

Bloom was of the same mindset as Chesterton and Wiener when he wrote about the growing “incoherence” of education.

…the crisis of liberal education is a reflection of a crisis at the peaks of learning, an incoherence and incompatibility among the first principles with which we interpret the world, an intellectual crisis of the greatest magnitude, which constitutes the crisis of our civilization… the crisis consists not so much in this incoherence but in our incapacity to discuss or even recognize it.

To that end, Robert Silverberg’s Tower of Glass was amazingly on point. I’m usually reading one fiction book, one non-fiction book, and one e-book at the same time. I happened to be reading Tower of Glass at the same as The Closing of the American Mind and The Everlasting Man. All of them touch strongly on how religion is innate to the human experience and how it’s impossible to have a human who is not bound by some form of religious feeling. If it isn’t explicit, it will be implicit, and probably directed toward some thing or some person that shouldn’t be treated religiously.

In Tower of Glass, tech billionaire Simeon Krug has made his fortune creating modified-DNA androids. They are human, flesh and blood, even if each has their DNA modified to emphasize some trait needed for their intended work. As Krug searches for some means of communicating with the Eye of God (NGC-7293), his androids seek a means of communicating with Krug, but as a god, not as a human.

Silverberg works a lot of the Western canon—the canon whose absence Bloom laments—into this amazing story of religious fervor, slavery, and human failings.

Is this what being human is like? These decisions, these doubts, these fears? Why not stay android, then? Accept the divine plan. Serve, and desire no more. Step away from these conspiracies, these knotted emotions, these webs of passion. He found himself envying the gammas, who aspired to nothing. But he could not be a gamma. Krug had given him this mind. Krug had created him to doubt and suffer.

The most weirdly on-topic book I read this year was Alan E. Nourse’s The Blade Runner. This is the book whose title became the title of the film adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. Androids would have been on-topic this year, too, with its use of androids to delve into what makes us human, but instead I read Dick’s The Divine Invasion. It’s filled with Christian and Jewish philosophy about God and how God interacts with the world. Rather than being about what makes us human, it’s about what it means to worship. What does it mean for God to love mankind? What does it mean to accept or reject God? What do ethics mean to God? What does it even mean to be human when there is a God and a reality beyond the physical?

Which means, of course, that it really is about what makes us human.

Nourse’s Blade Runner, on the other hand, begins with a completely unbelievable science fiction scenario. The United States government has implemented a very unpopular national health care law that both discourages people from seeking health care and discourages doctors from providing it. The rationing of health care that this top-heavy scheme requires are considered benefits rather than problems. Rationing health care is a means to stave off overpopulation.

And against the backdrop of this mess of superficially well-intentioned government incompetence comes the Shanghai Flu…

Completely unbelievable.

“There’s nothing personal about it, it’s just part of their policy.”

“Well, it may not be personal to them, but it’s plenty personal to me.”

It is not at all surprising that a C.S. Lewis novel would address the relationship between man and god, but Till We Have Faces was surprising nonetheless. It’s a first-person story, a diary, meant by its ancient Greek writer as a rant against the gods. That’s something Lewis himself was familiar with, according to Loconte, after losing so many friends in World War I.

There’s a real sense of wonder at the divine in this book, and how incomprehensible gods must be to men.

Have you forgotten what we are to say to ourselves every morning? ‘Today I shall meet cruel men, cowards and liars, the envious and the drunken. They will be like that because they do not know what is good from what is bad. This is an evil which has fallen upon them not upon me.

Not everything that I read this year was about the deep philosophies of God and man. I found a new fantasy series at the New Braunfels library sale to enjoy, and while Gardner Fox is not quite up to the level of Edgar Rice Burroughs at his best, Kothar: Barbarian Swordsman and Kothar of the Magic Sword are both a lot of fun, filled with sorcery and monsters and set in a far future where little technology remains. Giant worms, huge spiders, undead, and demons.

So a little on topic after all.

Likewise fun is Kevin Anderson and Sarah Hoyt’s Uncharted, an alternate history where magic arrived in 1759 with Halley’s Comet. The great sorceror Benjamin Franklin sends Meriwether Lewis and William Clark into the uncharted wilderness west of civilized America to regain contact with Europe and to explore the realm of monsters.

The absolutely beautiful Forgotten Beasts of Eld by Patricia McKillip, while not explicitly set in a far-future world, is clearly set in an aging one.

“You have nothing to fear from [the dragon],” Sybel said. “He is old, and he wants nothing now but his dreams, and his gold securely about him. He is pleased with his cave.”

The main character is what we today would call an Odd, someone “on the spectrum”. She does not understand people; human interactions are puzzles to be solved or ignored. She has special abilities that she cannot pass on to others, and these abilities make her powerful—and desirable in the mundane world—but her lack of understanding of human nature often causes her to fail. Of all the evils done to her, the unforgivable sin is stealing her will in order to use her powers for worldly things.

I also read several fascinating autobiographies. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s My Grandfather’s Son is a tribute to a man young Thomas saw as “larger than life”, “the greatest man I have ever known.” Thomas would recognize Chesterton’s meaning when Chesterton wrote that “There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there.” Thomas didn’t stay there, of course, and that’s the bulk of this very personal history.

Death is a Lonely Business is not Ray Bradbury’s autobiography. Instead, it’s a mystery about a young writer from Illinois, nicknamed the Martian by his neighbors, who doesn’t drive, lives in Venice in California, submits to pulp magazines, and whose first big break came with a story in “The American Mercury” in the forties.

Hm… It appears that there is more than one mystery in this mystery novel.

Happy New Year! Here’s to 2023 and another year of great books and Great Books.

In response to The Case for Books in 2015: In 2015, I read a lot of books… and bought a lot more. That’s not a sustainable market plan.

adventures

- Review: Hide Me Among the Graves: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- What would you do for immortality? For a second chance at love? Tim Powers’s vampires offer the artists of the Rosetti family the chance for both.

- Review: Kothar of the Magic Sword: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Heavy metal swords & sorcery at its finest.

- Review: Kothar—Barbarian Swordsman: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- A barbarian like Kothar with a sword like Frostfire is always an exciting adventure.

- Review: The Forgotten Beasts of Eld: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Sybel is an odd, and with all of the problems that modern odds face makes a very compelling protagonist.

- Review: The Gods of Mars/The Warlord of Mars: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The second and third volumes in Burroughs’s Mars series expand on the themes he introduced in the first, especially the evils of slavery and political elites.

- Review: Uncharted: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Benjamin Franklin sends Meriwether Lewis to seek out a northwest passage, and an alternate route to the old world across a very Arcane America.

books

- Friends of the New Braunfels Public Library Annual Book Sale

- The annual New Braunfels Library sale is well worth a visit if you live nearby.

- Goodreads: Year in books 2022 at Jerry@Goodreads

- Both the shortest and longest books I read in 2022 were cookbooks. The most popular was Alan Moore’s Watchmen.

- My year in food: 2022

- From New Year to Christmas, from ice cream to casseroles, from San Diego to New Orleans, from 1893 to 2014… and beyond!

- Temple Public Library Book Sale

- The Temple Public Library has a great book sale twice a year. I’ve picked up some wonderful novels, nonfiction, and cookbooks there.

computer history

- Our Cybernetic Future 1972: Man and Machine

- In 1972, John G. Kemeny envisioned a future where man and computer engaged in a two-way dialogue. It was a future where individual citizens and consumers were neither slaves nor resources to be mined.

- Our Cybernetic Future 2023: Entropy in Action

- Studying the past, we can improve the future. Studying the futurists of the past, we can learn the tools to improve the future.

- Review: As We May Think: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- “This is possibly the most influential essay in the history both of science fiction and computers. I’m almost surprised that we didn’t name computers ‘the memex’ given how often this essay comes up when talking about how our present was inspired by past futurists.”

- Review: The Human Use of Human Beings: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Entropy is a measure of disorganization; information is a measure of organization. Wiener saw that as something more and more difficult not just for children but for adults to grasp. And an inability to accept entropy means an inability to fight entropy.

humanity

- Review: Dorothy Parker Stories: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Extremely repetitive stories, both the dialogue and the inner monologues. Sometimes her cardboard characters even use the same conversations as different characters in previous stories.

- Review: My Grandfather’s Son: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- This book is Thomas’s tribute to “the greatest man I have ever known”.

- Review: The Blade Runner: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Billy Gimp is a bladerunner, an black market provider of medical supplies to underground doctors.

- Review: The Essential Calvin and Hobbes: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Calvin’s idealized life is unbelievable—and unbelievably funny.

- Review: Watchmen: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Watchmen, in some ways, follows a very similar character to the eponymous hero in V for Vendetta.

mysteries

- Review: Death is a Lonely Business: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Amidst the dying circus along Venice Beach, the aging and forgotten stars of Hollywood are dying as well. Is it murder?

- Review: N or M?: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Christie captures a sense of vulnerability and paranoia among the British during the second World War.

- Review: The Final Solution: A Story of Detection: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The limitations of logic in the face of horror.

- Review: The Mysterious Affair at Styles: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Hercule Poirot’s first appearance does not disappoint.

religion

- Review: The Closing of the American Mind: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The root cause of America’s higher education problem is a deep “lack of belief in the university’s vocation.” It’s mirrored by a general lack of belief throughout the Western world.

- Review: The Divine Invasion: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Filled with Christian and Jewish philosophy about God, Dick asks the really big questions: what does it mean for God to love mankind, to be in a battle with his own creation, to transcend his own physical laws?

- Review: The Everlasting Man: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Chesterton argues against the Darwinian idea that since mankind had evolved from the animals, man is no different from an animal, and against the Darwinian idea that the difference between paganism and Christianity is simply a matter of time and evolution.

- Review: Till We Have Faces: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- C.S. Lewis’s main character rails against the gods, and hits herself—and her family—instead.

- Review: Tower of Glass: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Just as men ask too much of the universe, Simeon Krug’s androids ask too much of their creator.

war

- Review: A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The battlefields of the first World War shaped everyone who went through it. Tolkien and Lewis were affected very differently than their contemporaries, however, and it showed in their writings and in their lives.

- Review: A New Birth of Freedom: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- An amazing summary of Lincoln’s interpretation of the American Founders, and his convictions about the inherent wrongness of slavery.

- Review: Code Duello/Computer War: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Cold war stories set in the far future, failing to develop any of the really interesting ideas in that far future and hiding them as well as possible behind some very tedious exposition.

- Review: Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- What was it like to be a hoplite in Greek phalanx warfare? From the armor to the weapon to the sacrifices and preparations for battle, each essay in this collection covers a very specific facet of the ancient Greek soldier’s experience.

- Review: With the Old Breed: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- The war that Sledge describes is like a horror movie, but more horrific. “It can be appreciated only by someone who has experienced it.” But he makes the feelings of people who were there easier to understand.

More 2022

- My year in food: 2022

- From New Year to Christmas, from ice cream to casseroles, from San Diego to New Orleans, from 1893 to 2014… and beyond!

More annual retrospectives

- My year in food: 2022

- From New Year to Christmas, from ice cream to casseroles, from San Diego to New Orleans, from 1893 to 2014… and beyond!

- My Year in Food: 2021

- From Washington DC to San Diego and one or two places in between, it’s been a very good year for food.

- My Year in Books: 2021

- From Louis l’Amour to slavery to H. Rider Haggard, it’s been a very good year in books.

- The Year in Books: 2020

- What did 2020 have to offer in books?

- The Year in Books: 2019

- 2019 was a great year for reading old books.

- One more page with the topic annual retrospectives, and other related pages

More books

- My Year in Books: 2023

- It’s been a slower year in books than previous ones, but it was still a year of fantasy in the past, in the future, and across time, as well as an unplanned foray into people doing the impossible and changing the world.

- My Year in Books: 2021

- From Louis l’Amour to slavery to H. Rider Haggard, it’s been a very good year in books.

- The Year in Books: 2020

- What did 2020 have to offer in books?

- The Year in Books: 2019

- 2019 was a great year for reading old books.

- The Year in Books: 2018

- Have I got some recommendations for you…

- One more page with the topic books, and other related pages