The Year in Books: 2018

This was a very nice, and small, haul from nearby Temple’s Public Library sale—plus one book from McWha Books and one from Amazon. I still have three of these to read, and am currently halfway through Kip Thorne’s book, which I fully expect to be on next year’s recommendations.

According to Goodreads, I read 133 books last year; according to my own databases, I bought 134. That’s teetering on the edge of sustainability. The latter number also includes reference books downloaded to my tablet that I don’t need to read per se, and instruction manuals that I have read but that don’t get counted on Goodreads.

Which means I am making a dent in my to-read shelf/ves, albeit slowly.

According to Goodreads, the shortest book I read was Lawrence W. Reed’s Great Myths of the Great Depression. At only twenty pages, it’s a good overview of the period as seen through the eyes of the people who lived it.

The longest book was The Essential Ellison, which, unless you want to know more about Ellison’s work, I don’t recommend. Unfortunately, when I read Ellison I tend to find his introductions more interesting than his works, and this book contains other people’s introductions, not his.

The most popular book I read this year was Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, which I highly recommend, preferably before you see the movie if you haven’t yet. I saw the movie and still thoroughly enjoyed the book. The sequel, Speaker for the Dead was very different and just as enjoyable.

The least popular book, not surprisingly, is a guide to a computer that was discontinued long before Goodreads was founded. Goodreads was launched at the very end of 2006, and the Tandy 200 was a 1985-era computer1. So it’s not surprising that I needed to request an update of the bibliographic data and cover for Lien’s books.

As you can tell from my other recent entries, I’ve been dabbling in BASIC again, mainly because of the TRS-80 Model 100/200. The first BASIC book I read was David Lien’s instruction manual for the TRS-80 Model I—it came with the used Model I that I purchased in high school. It was so readable it made all subsequent BASIC books over the years a disappointment. So when I saw, at Tandy Assembly, that he’d written a book for the Model 100 and 200, I snapped them up. This book lived up to the reputation I’d built up for Lien, and I am now comfortable writing useful—and not-so-useful—BASIC software for the 100/200 line.

The highest-rated book was The Deplorable Gourmet•, which has a 5.00 average. This is undoubtedly because of its dedicated clientele. But truly, if you need a book of diverse cooking views, The Deplorable Gourmet• is your book.

S.W. Welch’s in Montréal is a small—and expensive—bookstore, but packed with great books.

I began the year with Chesterton and ended it with Machen, both eBooks downloaded from Gutenberg, and I recommend them both for similar reasons. In The New Jerusalem Chesterton describes “the Jewish Question” from a British viewpoint after Balfour and before World War II. Arthur Machen wrote about the angels of Mons in a not-particularly-convincing manner, but in the desolation of the First World War people were geared to believe in supernatural assistance. If you’re interested in phenomena such as Orson Welles’s more famous Martian invasion, read Machen’s collection of related short stories, The Angels of Mons.

By far the most fascinating book I read this year was Philip Van Doren Stern’s collection of President Abraham Lincoln’s writings. It collects and excerpts Lincoln’s writings from before he got into politics and up through his presidency. It is amazing, reading these works just before the Civil War, not how much Lincoln shared the prejudices of his colleagues, but how much his principles allowed him to rise above his prejudices. He could write or say something just as horribly prejudiced as anyone else of his era, apply what we would now call conservative principles, and then end his speech or letter with something so unequivocally un-prejudiced and right as to astound.

His colleagues, such as Stephen Douglas, started from much more compassionate ideas, but their compassion was rooted in principles that we would now call elitist, that they knew better what other people ought to do. That they needed to force other people to act in their own best interests, because they were too stupid to do so without coercion. And so their principles reinforced their prejudices and made them worse.

In fiction, I have finally read a book that has been recommended to me forever, and it was well worth the read. “There are still old knots that are unrecorded,” wrote Annie Proulx in The Shipping News•, “and so long as there are new purposes for rope, there will always be new knots to discover.” Proulx’s tale of a man dragged to Newfoundland by an aunt combined with circumstances is impossible to describe without giving away the little things that make it an amazing read.

Similarly, “Knowledge was never simply born in the human mind,” wrote Salman Rushdie in The Enchantress of Florence•, “it was always reborn. The relaying of wisdom from one age to the next, this cycle of rebirths: this was wisdom. All else was barbarity.”. Rushdie’s fantasy about a foreigner showing up in “the Emperor’s City” is filled with subtle magic, bravery, and the deception of storytelling in a world as shifting as the desert sands.

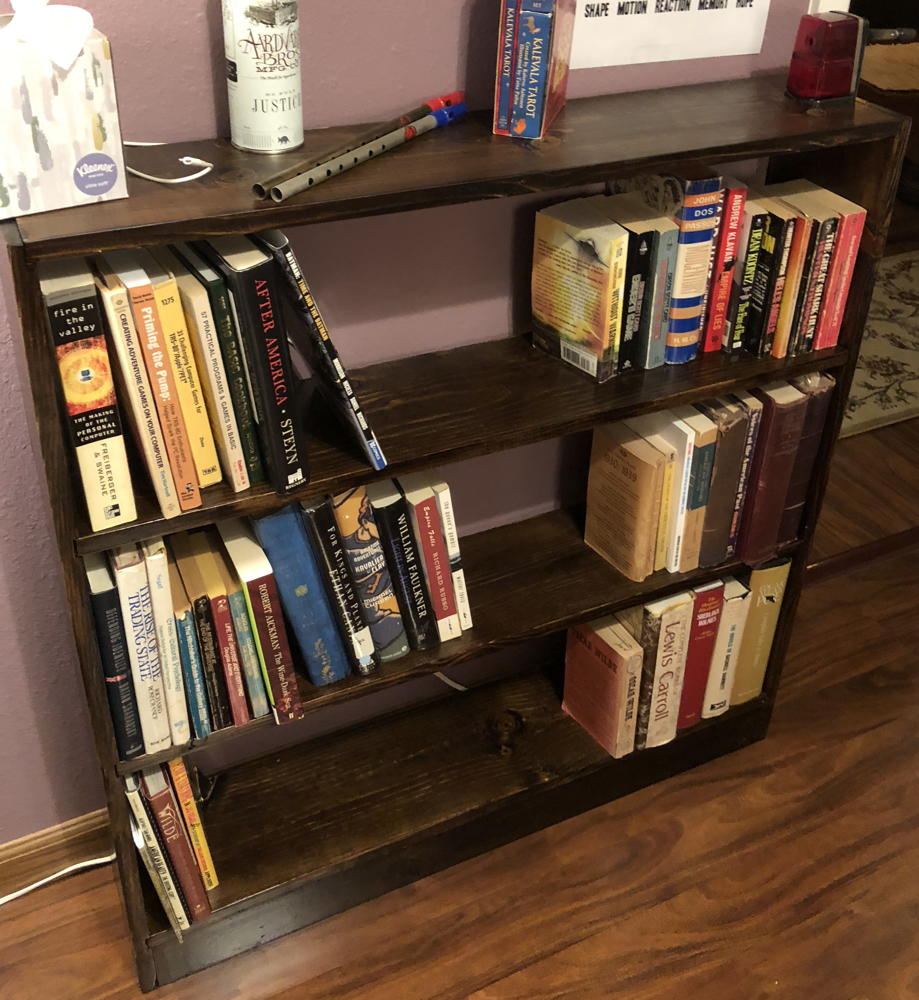

Of course, new books means building new bookcases.

The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour). — Vladimir Nabokov (Speak, Memory•)

If, on the other hand, you’re looking for books about writing, I haven’t found much better than Nabokov’s memoir or A.S. Byatt’s musings on why historical novels appeal so much as stories.

I think the fact that we have in some sense been forbidden to think about history is one reason why so many novelists have taken to it. — A. S. Byatt (On Histories and Stories•)

It may also explain why novels about the future appeal so much. Two of the most fun reads I had this year were Niven and Pournelle’s Oath of Fealty• and Ken Follett’s• On Wings of Eagles•. The former is a few non-dystopic months in the life of an arcology. Massive housing complexes get short shrift in science fiction, but Todos Santos is presented with both drawbacks and benefits. It shows us why people are willing to house themselves in giant communities cut off from the rest of the world—and why it sometimes might be a good thing.

Follett, on the other hand, is writing historical fiction, albeit a history from only a few years before he wrote it. A young global computer company finds its employees kidnapped by the state, in a turbulent country overrun by religious fanatics. Some of the employees are imprisoned in prisons, and all are imprisoned in the country—they are not allowed to leave. I read it a couple of decades ago when the events it portrays were much closer, but it’s just as exciting now.

The two stories also have something else in common which I won’t spoil.

In response to The Case for Books in 2015: In 2015, I read a lot of books… and bought a lot more. That’s not a sustainable market plan.

I can’t find any reference to when the Model 102/200 line was discontinued, but I have a vague memory it was some time in the nineties.

↑

recommendations

- The Deplorable Gourmet• (paperback)

- Every normal cook must be tempted at times to spit a small chicken, hoist the black coffee, and begin slicing potatoes.

- The Enchantress of Florence•: Salman Rushdie (paperback)

- An enchanting fantasy.

- Great Myths of the Great Depression: Lawrence W. Reed

- “To properly understand the events of the time, it is appropriate to view the Great Depression as not one, but four consecutive depressions rolled into one. Professor Hans Sennholz has labeled these four ‘phases’ as follows: the business cycle; the disintegration of the world economy; the New Deal; and the Wagner Act.”

- Oath of Fealty•: Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle (hardcover)

- I have read a lot of science fiction about massive housing complexes, and all of them present them as dystopias, or at least an unpleasant thing that be borne due to other circumstances. Niven and Pournelle present a uniquely pleasant view of their arcology, Todos Santos in the Los Angeles area.

- On Histories and Stories•: A.S. Byatt (paperback)

- Byatt “considers the renaissance of the historical novel.”

- On Wings of Eagles•: Ken Follett (hardcover)

- An extraordinarily exciting story about Americans doing what they set out to do.

- The Shipping News•: Annie Proulx (paperback)

-

An amazing story of finding being dragged by family into a new life worth living.

An amazing story of finding being dragged by family into a new life worth living.

- Speak, Memory•: Vladimir Nabokov (paperback)

- Nabokov’s biography includes hidden insights into his various works, as well as to Nabokov himself.

history

- Abraham Lincoln’s conservative principles

- Reading Lincoln, it seems that both conservative thought and anti-conservative thought really hasn’t changed much in a century and a half. Though less racist for his time, he was still racist. But his adherence to conservative principles enabled him to overcome his prejudices while his contemporaries who were not conservative sank deeper into racism.

- Goodreads: Year in Books 2018 at Jerry@Goodreads

- Not surprisingly, the longest book I read was Harlan Ellison, and the highest rated was a pirate-themed cookbook.

- The New Jerusalem: G. K. Chesterton at Project Gutenberg (ebook)

- A series of essays coinciding with Chesterton’s pre-1920 travel to Israel and the Holy Land.

- Tandy Assembly 2018

- Tandy Assembly was earlier this November, and I have never seen so many Radio Shack computers in one spot. Also, my love affair with daisy wheels is rekindled.

- While sorrowful dogs brood: The TRS-80 Model 100 Poet

- Random poetry: a BASIC random primer and a READ/DATA/STRINGS primer, for the TRS-80 Model 100.

More 2018

- 2018 in Photos

- For photos, memes, and perhaps other quick notes sent from my mobile device or written on the fly during 2018.

More annual retrospectives

- My year in food: 2022

- From New Year to Christmas, from ice cream to casseroles, from San Diego to New Orleans, from 1893 to 2014… and beyond!

- My Year in Books: 2022

- From Hoplites to Venice… California, this has been a year in books filled with war, evil, and the dehumanization of man. But it’s also been a year of high adventure, magic, and larger-than-life heroes.

- My Year in Food: 2021

- From Washington DC to San Diego and one or two places in between, it’s been a very good year for food.

- My Year in Books: 2021

- From Louis l’Amour to slavery to H. Rider Haggard, it’s been a very good year in books.

- The Year in Books: 2020

- What did 2020 have to offer in books?

- One more page with the topic annual retrospectives, and other related pages

More books

- My Year in Books: 2023

- It’s been a slower year in books than previous ones, but it was still a year of fantasy in the past, in the future, and across time, as well as an unplanned foray into people doing the impossible and changing the world.

- My Year in Books: 2022

- From Hoplites to Venice… California, this has been a year in books filled with war, evil, and the dehumanization of man. But it’s also been a year of high adventure, magic, and larger-than-life heroes.

- My Year in Books: 2021

- From Louis l’Amour to slavery to H. Rider Haggard, it’s been a very good year in books.

- The Year in Books: 2020

- What did 2020 have to offer in books?

- The Year in Books: 2019

- 2019 was a great year for reading old books.

- One more page with the topic books, and other related pages