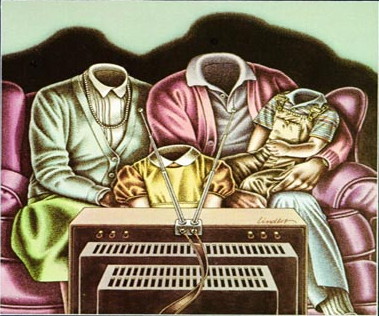

Mimsy Review: Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

“Typography assisted in the growth of the nation-state but thereby made patriotism into a sordid if not lethal emotion.”

Around the net

Amusing Ourselves to Death is a disjointed effort to prove that the speed of modern communications is killing us, but it ignores basic features of modern communications, such as the ability of both sides to respond; and to the extent that modern communications empowers the individual he sees that as an evil, preferring the bundling of individuals by self-appointed elites as in the age of Tammany Hall.

| Recommendation | Trivial |

|---|---|

| Author | Neil Postman |

| Year | 1985 |

| Length | 188 pages |

| Book Rating | 2 |

Amusing Ourselves to Death• is extraordinarily sloppy. On the very first page, he writes about a statue of a hog butcher that may or may not exist in Chicago. That may have been poorly-worded sarcasm, but on the next page he speculates that because President Richard Nixon—after resigning—advised Senator Ted Kennedy to lose twenty pounds if he wants to run for president,

…it would appear that fat people are now effectively excluded from running for high political office. Probably bald people as well. Almost certainly those whose looks are not significantly enhanced by the cosmetician’s art. Indeed, we may have reached the point where cosmetics has replaced ideology as the field of expertise over which a politician must have competent control.

Now, the conclusion may be true. But it is worded in such a passive-aggressive manner as to be near-useless. The evidence given—a disgraced politician’s dieting advice to a man whose biggest impediment to national office was not weight issues but leaving a woman to drown slowly overnight—simply doesn’t make any sense except as sarcasm. And not only was Kennedy’s weight not the biggest roadblock keeping him from the Oval Office, but the leap from Nixon’s advice on weight to baldness is done without any proffered evidence. And yet, this is not sarcasm: this is the thesis of the book, that appearance has become more important than substance.

He speaks a lot about Aldous Huxley in this book, contrasting Huxley’s vision of the future with George Orwell’s. But even that is impossibly vague, starting right in the first chapter when he writes that “We are all, as Huxley says someplace, Great Abbreviators…”.

He describes his purpose at the start of chapter two:

It is my intention in this book to show that a great media-metaphor shift has taken place in America, with the result that the content of much of our public discourse has become dangerous nonsense. With this in view, my task in the chapters ahead is straightforward. I must, first, demonstrate how, under the governance of the printing press, discourse in America was different from what it is now—generally coherent, serious and rational; and then how, under the governance of television, it has become shriveled and absurd.

While it is difficult to disagree with the premise—that our media discourse is dangerous and absurd nonsense—it is difficult to read his praise of the serious and rational press immediately after reading Deadlines & Monkeyshines.

I have a suspicion that any time you have a news media class who think it is their purpose to shape public opinion toward an anointed position, you will have absurdity. And that this was as true in the days of Sherman Duffy’s intellectual-free sports, the Chicago Tribune’s attempted reformation of the English language, and Walter Duranty as it is today. Duranty’s whitewashing of Soviet mass murder was as much dangerous nonsense as any blogger’s or television anchor’s words today.

He does not like numbers. He goes through a long anecdote about Aristotle, who believed that women had fewer teeth than men; he never bothered to count them, for this would have been

…both vulgar and unnecessary, for that was not the way to ascertain the truth of things. The language of deductive logic provided a surer road.

We must not be too hasty in mocking Aristotle’s prejudices. We have enough of our own, as for example the equation we moderns make of truth and quantification. In this prejudice, we come astonishingly close to the mystical beliefs of Pythagoras and his followers who attempted to submit all of life to the sovereignty of numbers. Many of our psychologists, sociologists, economists and other latter-day cabalists will have numbers to tell them the truth or they will have nothing. Can you imagine, for example, a modern economist articulating truths about our standard of living by reciting a poem? Or by telling what happened to him during a late-night walk through East St. Louis?… Yet these forms of language are certainly capable of expressing truths about economic relationships, as well as any other relationships, and indeed have been employed by various peoples. But to the modern mind, resonating with different media-metaphors, the truth in economics is believed to be best-discovered and expressed in numbers. Perhaps it is. I will not argue the point.

In other words, “I will make an absurd argument filled with dangerous nonsense, and when I get to the point where it is at its most dangerous, I shall not argue the point.”

This book, remember, is subtitled “public discourse in the age of show business”. Part of the dangerous and absurd nonsense of today’s public discourse is that you can make public policy by deciding first on policy and then finding anecdotes to support that policy. But public policy affects all of the public, and that means examining the mass of people—the huge number of them—rather than searching for outliers that fit your preconceptions.

In a sense, this entire book purports to argue the opposite point, that this show-business style of policy-making is in fact dangerous and absurd. And that one form of truth-telling—the print press—is more capable of expressing truth than another form—television.

He recognizes this, because he goes on to say, after employing this epistemological relativism, that he does not intend to make a case for it—despite literally having just done so.

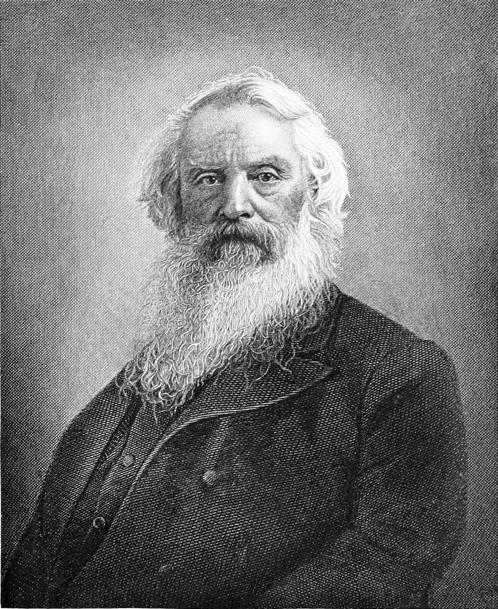

After Morse, everything went to pot.

Throughout the book there is a lack of thought or explanation that borders on the shaggy dog. Here, for example, he talks about English newspaperman Benjamin Harris, who fomented persecution of Catholics in England:

Before he came to America, Harris had played a role in “exposing” a nonexistent conspiracy of Catholics to slaughter Protestants and burn London. His London newspaper, Domestick Intelligence, revealed the “Popish plot,” with the result that Catholics were harshly persecuted. Harris, no stranger to mendacity, indicated in his prospectus for Publick Occurrences that a newspaper was necessary to combat the spirit of lying which then prevailed in Boston and, I am told, still does. He concluded his prospectus with the following sentence: “It is supposed that none will dislike this Proposal but such as intend to be guilty of so villainous a crime.” Harris was right about who would dislike his proposal. The second issue of Publick Occurrences never appeared. The Governor and Council suppressed it, complaining that Harris had printed “reflections of a very high nature,” by which they meant that they had no intention of admitting any impediments to whatever villainy they wished to pursue. Thus, in the New World began the struggle for freedom of information which, in the Old, had begun a century before.

What does Postman mean to say in that paragraph? In what way is publishing fake conspiracies part of the struggle for freedom of information? How does Harris’s printed persecution of Catholics support the argument that the printed press was “coherent, serious and rational”?

He belittles the “information-action ratio” of electronic communications, starting with the telegraph—but makes no attempt to measure that ratio before the telegraph. He talks about novelty as if the telegraph created our need for novelty, which completely ignores the popularity of bestiaries and maps with dragons. Telegraph filled a need for curiosities with things that actually happened, rather than things that never existed.1

He doesn’t even really make an attempt to measure the ratio after the telegraph either—just a thought experiment to make it appear low.2 But even before the telegraph, what happened in DC affected Baltimore and its residents. The difference was that, before the telegraph, only the rich—only the people trying to influence DC to their interests as on, say, railroad rights—had the wherewithal to do anything about it. The telegraph meant that when a company tried to influence congress regarding the hinterlands, the hinterlands could learn about it—and respond—in days rather than months.

He makes the explicit assumption that the telegraph went only one direction—that learning of a disaster elsewhere, you feel impotent because you have no means of offering support. That hearing of political perfidy, you have no means of making your displeasure known.

For the first time, we were sent information which answered no questions we had asked, and which, in any case, did not permit the right of reply.

The impotence he talks about is not a result of speed but of distance, even were it impotence. Without the speed, we still learned of things happening far away, we just learned about them after it was too late to respond. That’s true impotence.

The evils of the telegraph are completed with the invention of the photograph. Here, as well, he is somewhat incoherent. He goes in one paragraph from saying that photos cannot be taken out of context because they have none, to saying that it is easy to take them out of context and this is part of why they’re bad.

The ultimate solution to this assault on reason is clear: we must return to a time when information was slow, where there was no means of verifying what authorities told us. Regardless of the caveats he adds, the picture he paints of instant communications as evil requires it.

It isn’t TV that is evil in his telling. It is the immediacy of electronic news, and the ability of photography to store the world without filtering it through (someone else’s) language.

If this book were merely a discussion—a study—of the differences electronic communications made upon our culture compared with print, it might be interesting—we could do something with it, reply to it, in his words. But Postman despises study—he despises the means by which we use numbers to understand the world as a whole, instead of merely a collection of anecdotes. Postman is what he hates. A bringer of evil that cannot be changed, in the form of discordant stories.

Chapter six, The Age of Show Business, is dedicated to explaining that television does not like to show people thinking, because it is boring. He provides no counter-examples of the printed word showing people thinking, for that would undercut his purpose. Because, while television can show thinking but chooses not to, the printed word cannot show it at all. It’s all finished copy, often presented as if it were extemporaneous. It’s a fact I’m not even sure he realizes, because he praises the printed remarks of great men in previous chapters as examples of public discourse before the scourge of television, with no recognition that printed text often differs from the spoken speech. Congress is rife with examples of politicians deeming that something was said rather than actually saying it. Print can do that. One might even, in Postman’s language, say it encourages that kind of deception. Television doesn’t.3

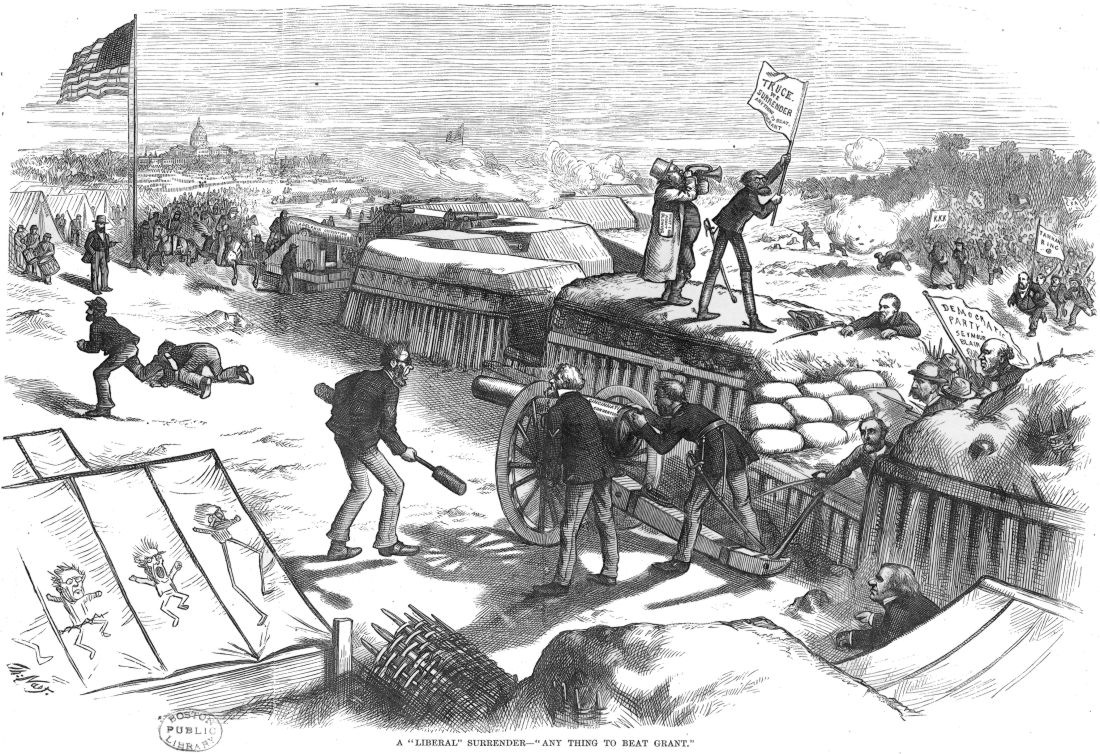

Note, in the upper right, that the anti-Grant liberal Republicans are surrendering not just to the Democrats, but to the Ku Klux Klan and the Tammany Hall corruption ring.

It may be that he is aware of the power that faster communications gives the individual voter and simply dislikes it. In looking fondly back on the Tammany Hall system of bundling voters, he dismisses our modern alternative with “There may be a case for choosing the best man over party (although I know of none.)”

Part of his comparison of Huxley with Orwell is that Orwell thought history would be rewritten by the anointed; Huxley thought that people would no longer care about history. It’s a potentially interesting argument, but not one he makes well.

Toward the end, as he is marshaling his arguments, he writes that Orwell was wrong—except for where he was right, which was two of the most populous nations in the world, Russia and China.

He ignores that even on television, the anointed rewrite history. They remove cigarettes from smokers, and guns from security guards.

Throughout the book, he always jumps to the easiest argument. For example, he rails against the idea that personal computers4 can replace teachers. But when he makes comparisons of interactivity, it is television that you cannot ask questions of. He ignores the potential interactivity of the personal computer.

He continually praises the “slow-moving printed word”. You might argue that television has been supplanted by the Internet—that his thesis was true but the danger he warned of has been averted by the instant interactivity now available on our mobile computers. But he specifically says that it is not television that is the problem; television is the symptom; the problem is the speed of electronic communications and the use of photographs over words.

In the final pages of the penultimate chapter, he finally starts bringing statistics to bear not against television but against one television series, an educational show called The Voyage of the Mimi that aired on PBS.

The final chapter, however, is the saddest and most passive-aggressive. He wishes to provide a solution to the problem, but reluctantly rules out complete elimination of television; he notes that:

…many civilized nations limit by law the amount of hours television may operate and thereby mitigate the role television plays in public life. But I believe that this is not a possibility in America. Once having opened the Happy Medium to full public view, we are not likely to countenance even its partial closing.

“Still,” he closes the argument wistfully, “some Americans have been thinking along these lines.”

He’s also “fond of John Lindsay’s suggestion that political commercials be banned from television”, even though he’s spent the entire book arguing that it is not the content of television that is the problem, but the way that the presentation teaches us to think. He’s spent the entire book arguing that television teaches us to carry the same processes into the rest of the world, so that the rest of the world must also act like television to be heard. Simply banning political commercials from television won’t stop politicians from acting like television.

Which is not even to go into (and he doesn’t) that banning political commercials will not ban the form of political commercial known as “the news”. He either doesn’t even recognize this, or he ignores it because it’s not an easy discussion.

Superficial and easy. That’s the book in a nutshell.

He finally comes up with two pages and two solutions: a “nonsensical” solution and a “desperate” solution. The nonsensical solution is Monty Python and Saturday Night Live-like satires of television, to be aired on television “to induce a nationwide horse laugh over television’s control of public discourse.” But of course this won’t work, he says, because the satires themselves would have to be television-friendly and would thus become what they satirize.

The desperate answer is to improve teaching in schools.

This is the conventional American solution to all dangerous social problems, and is, of course, based on a naive and mystical faith in the efficacy of education. The process rarely works.

In this case it is unlikely to work because computers and word processors are insinuating themselves into education, and computers and word processing are part and parcel with television in the same dangerous social problem.

This is a bad book. It is not necessarily a bad thesis. It’s just poorly argued. He isn’t saying that television is bad. He’s saying that electronic communication is bad, especially when combined with pictures. But he doesn’t argue that electronic communication is bad, he argues that television is bad—and broadcast television at that. It’s like arguing that legumes are bad for health, and basing all arguments on peanut cluster candy.

And, even though his argument begins with the telegraph, he makes no attempt to use or even discuss the ability for electronic communications to go both ways. Given that his only solutions involved monolithic, top-down changes in American life, I suspect he simply cannot see the empowering nature of these new technologies; that despite his own fear of statistics, his own biases make him completely blind to individuality bubbling up. If the only processes you see are the giant boot stamping mankind, then the situation is hopeless. But if you can see the thousands of tiny pins pointing upward, perhaps this new technology will work out after all.

There’s a case for telegraph and electronic communications harming our cultural creativity, but it’s difficult to make the case that it created our need for new things.

↑Which perhaps explains his disdain for averages and medians earlier expressed.

↑It has its own deceptions, of course, such as the cut between unrelated facts that makes them appear related, but while that deception is exceptionally effective under television, it also exists in print.

↑He calls them micro-computers, the then-current term.

↑

Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

Neil Postman

Recommendation: Trivial

If you enjoyed Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business…

For more about media, you might also be interested in The evolution of news to candy, The Powers That Be, Spin Cycle: Inside the Clinton Propaganda Machine, and The gullible media and the chocolate factory.

For more about newspapers, you might also be interested in First, CNN came for InfoWars and Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism.

For more about television, you might also be interested in Tablo TV: Pause and rewind live television, Apple TV: Movie Streaming Overload, and Who killed broadcast TV?.

- Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business•: Neil Postman (paperback)

- This is a superficial treatment of television in mid to late twentieth century, that purports to be a general critique of modern, fast, electronic communications.

- Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism

- The past is a dark place to look into; despite all of the paeans to a golden age of journalism, John J. McPhaul describes a world very much like our own, but without the Internet to shine a light on journalism’s monkeyshines.

- Politics as Show Biz: Robert Stacy McCain at The Other McCain

- “About 15 years ago, I read two excellent books by Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death, and The Disappearance of Childhood. Postman was a liberal, but his analysis of the ways in which television shape our culture — including politics and education—was praised by many conservatives. When Postman died in 2003, it was an honor for me to be asked to write an obituary feature for the British Guardian.” (Memeorandum thread)

- Television and Political Correctness’ Safe Harbor for the Stupid: Ace at Ace of Spades HQ

- “A recent Matt Lewis column mentioned a book called Amusing Ourselves to Death, by Neil Postman, which was published in 1985. Yes, It’s Old (TM). Its central thesis struck a chord with me: That freedom and reason will be lost in America not in an Orwellian way, but in a Huxleyan one. Orwell’s vision was of a government ruthlessly suppressing books and changing written accounts of the past in order to change the thinking of the present.”