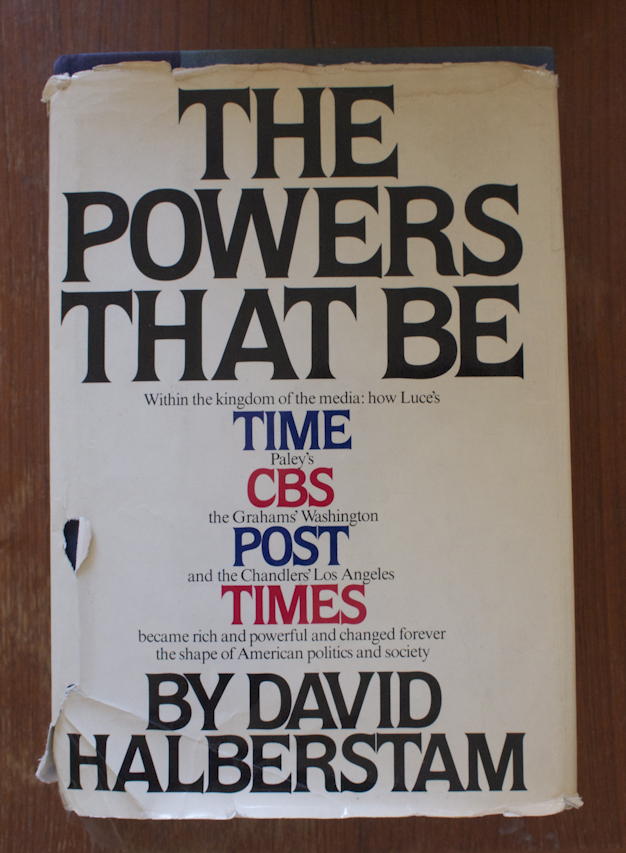

Mimsy Review: The Powers That Be

“A governing class needed a paper like the [New York] Times.”

Around the net

David Halberstam’s• tome about the growth of media power is repetitive, burdensome, it circles itself like an overweight prizefighter attempting to gain the advantage of the mirror, but like the aging boxer is filled with anecdotal glory.

| Recommendation | Special Interests• |

|---|---|

| Author | David Halberstam |

| Year | 1979 |

| Length | 771 pages |

| Book Rating | 5 |

I am currently writing a satire about the Washington, DC news media. David Halberstam’s• novel about the rise of the industry is a gold mine. The insights into how the press sees itself is invaluable. When writing about the Washington Post, Halberstam notes that “in Washington reporters were not only stroked during the day but invited to the best homes for dinner at night.”

The Powers that Be• is a rambling, shaggy dog of a story that ends in Watergate. Halberstam treats the news organizations that took part in it as if they were individuals, the New York Times and her younger brothers, the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post, and their cousins, Time Magazine and CBS, taking them from the formless void to Watergate. In the beginning, there was nothing; then great men toiled and created the journalistic principles that allowed for Nixon to get caught in the Watergate scandal. I almost think he’s saying that there were Watergates throughout the Roosevelt years, the Eisenhower years, and the Kennedy years; and only during the Johnson years did Vietnam provide the practice they needed to take on the president during the Nixon years.

The book is, basically, the story of the rise of the Washington press. The DC press is a lagging mirror to the rise of DC power as seen in Washington Goes to War. Halberstam describes FDR’s Washington revolution this way:

In the new order, government would enter the everyday existence of almost all its citizens, regulating and adjusting their lives. Under him, Washington became the focal point, it determined how people worked, how much they made, what they ate, where they lived.

This was how DC became what Halberstam called “the great dateline”. FDR was the lone professor in the Washington School of Journalism: he skillfully manipulated and dominated the news by always providing so much that “reporters never had time to go to other sources; if they tried, they might make today’s story better, but they would surely be beaten on tomorrow’s.”

It wasn’t just that the rise of the President’s power meant a rise in the DC press. The rise of the DC press is also the rise of the President. It’s easier to cover one man than to cover several hundred, and so that one man becomes more influential.

Those who were powerful and well-regarded in Washington were powerful and well-regarded within the profession. Journalism fed off government and government centered upon Washington.

While Halberstam does not approve of the power that this centralization provided the president, he does approve of the power that it provides journalism, the power to be a national moral force.

Part of the problem in Halberstam’s telling was that early on television gave itself away for free. This means it’s the advertisers that call the shots. It’s a little amazing to hear him talk about CBS getting its start by giving away programming—as if Halberstam were a dot-com pundit complaining about web sites giving away content for free. CBS’s free content gave them access to an audience for their advertising—which gave them better programming, but only in the eyes of their viewers, not in the eyes of the press.

When Halberstam describes the postwar years as “an era of almost mindless profit” it sounds like he’s dissing mindless profits. But then he goes on to describe just how well off these mindless profits made Americans:

…possessions which were limited to the rich in most societies, be it education or housing or automobiles, were by the late forties becoming available to the middle class here… an entire society seemed to reach for the middle class…

The problem for Halberstam is that this prosperity was matched by right-wing politics. Like many in the elite, making people happy—especially via free markets—isn’t a noble goal. He complained, for example, that in television, advertisers wanted ratings, which forced networks to “give the people what they wanted” rather than provide taste, or balance.

Things weren’t too much different in the print media. Organizations like the Los Angeles Times, the Washington Post, and Time were biased news organizations, under the control of the owners. Part of this story is the rise of the wall between the corporate side of news organizations and the reporting side, which was supposed to make the news more reliable.

In the old days of the New York Times, Ed Klauber wrote this about the journalist’s responsibility:

What news analysts are entitled to do and should do is elucidate and illuminate the news out of common knowledge or special knowledge possessed by them or made available to them by this organization through its sources. They should point out the facts on both sides, show contradictions with the known record and so forth. They should bear in mind that in a democracy it is important that people not only should know but should understand, and it is the analyst’s function to help the listener to understand, to weigh, and to judge, but not do do the judging for him.

By the time Vietnam and Watergate were over, it was definitely the job of the analyst to do some of the judging, and nowadays the “paper of record” regularly not only judges what facts to show within articles, but also what articles to completely suppress. As I write this, if you want to know what happened in Benghazi, you probably aren’t reading the New York Times.

One of the things that Halberstam goes back and forth on is the chumminess between DC reporters and DC politicians. Washington Post publisher Phil Graham, seeing President Johnson faltering, took it on himself to write a better speech for him. That was a bit much even for Halberstam. But in this long quote about Nixon’s fundamental character flaw in not liking the press, there’s an approval of the chumminess. As you read this, remember that it describes Nixon before Watergate; nor is it presented as an explanation of what in Nixon led to Watergate. It’s a description of why Nixon got bad press and the press got bad Nixon:

At the heart of the relationship between politician and journalist is a sense of trust. The one has to trust the other, each knowing the limits and frailties of the other’s profession. Politicians are allowed by reporters to dissemble within certain limits; reporters, in the eyes of politicians, are permitted to analyze and criticize within certain limits. But at the heart is a common denominator: each is trying to be essentially straight and honest, trying to be fair and accountable within the codes of their very different professions. The common bond had traditionally been a mutual love of politics, a love of the game itself. But Nixon did not really love the game.

In other words, if you play the press’s game, they’ll let you get away with murder. If the press, as both player and umpire, judges your “dissembling” honest within the beltway game, they’ll let you lie. But if you don’t play their game, you’ll seem both vindictive and petty. To a person who doesn’t see the game, it’s going to look a whole lot like Calvinball. This paragraph almost makes me sympathize with Richard Nixon.

Halberstam has a reputation for erecting giants in the fields he writes about; some of that comes through in some of his descriptions of historical figures. For example, Edward R. Murrow was “one of those rare legendary figures who was as good as his myth.”

One thing Halberstam does here is jump in time a lot; combined with his distaste for modern Republicans over the ones who like to get along, he sometimes confuses the two. When he says that the elite held TIME magazine magnate Harry Luce’s Republicanism against him, does he mean the Republicans who ended slavery and segregation, or the Republicans who failed to bask in the glory of those accomplishments?

There’s a similar tension in his description of Norman Chandler of the Los Angeles Times and Bill Paley of CBS. Now, part of this to me is a bit of an Ozymandian epic: he writes about the Chandlers as if they run Los Angeles and the only Chandlers I’ve heard of in 25 years of living in Los Angeles and San Diego is Chandler Bing from Friends and Raymond Chandler.

Halberstam describes Norman Chandler as:

a serious, dogged, Taft Republican, a man with a devoted belief in property rights and the perquisites of the ruling class.

which is to say, Halberstam explains, not a “kook right-winger” like his ancestors. But when he describes another Republican, CBS’s Bill Paley, Halberstam decides that even Taft was too right-wing: Paley was:

Not a right-winger, of course, not a Taft man, he was too modern for that…

Halberstam describes Harrison Gray Otis and Harry Chandler, the founders of the Los Angeles Times, as having “a passion against labor, against social reform”. But the events he’s describing are the prosecution of labor and social reformers who bombed the Los Angeles Times and killed 20 Times employees. Halberstam is even annoyed that the Chandlers continued memorializing the dead. In the end, Otis and Chandler defeated unions at the Los Angeles Times, which turned out to be a good thing, because later when other newspapers were tied down by their unions from taking advantage of new technologies, the Los Angeles Times was able to move forward. In a much later section where he talks about Norman Chandler, he says:

In fact, no one in those years ran a newspaper better in the strict financial sense than Norman Chandler ran the Los Angeles Times. Starting with the strong non-union base that General Otis and Harry Chandler had created, he was freer than most publishers to experiment in modern technology… the battle that General Otis had won some fifty years ago against the unions had permitted the Times to pioneer in the use of modern technology while unions were blocking modernization at comparable papers.

This is in contrast to the problems the Washington Post ran into:

There is no doubt that the Post through the years had lost control over the small factory where the paper was actually put together and printed, its printshop and pressroom. Yet, like many other newspapers, the Post needed desperately to move gradually into more modern, relatively labor-free technology, which in the past the unions had success fought.

Some of the more odd turns of phrase come from the section on the Washington Post. For example, when Eugene Meyer tried to hire Alan Barth, Barth almost turned down the job, because he thought the Post was conservative. Barth was a “committed New Dealer” under FDR. He asked Meyer “Are you really sure that you want a total libertarian on your paper?” It’s hard to imagine that the modern definition of libertarian, someone who wants as few government constraints as possible, fitting with being a “committed New Dealer”.

When he gets to the Post’s Phil Graham his twists became even more painful. Where, when describing right-wing kooks their flaws were magnified, with Phil Graham they are minimized. Graham was an alcoholic; what this meant was that he was “a man who was always going to break the rules, a man who would always need to be forgiven. And she [his wife, Katherine Graham] would always forgive him.”

There’s a very interesting section about the Los Angeles Times, where Halberstam goes directly from his description of Kyle Palmer’s machinations to Buff Chandler’s. Kyle used the paper’s power for conservative policies, Buff for progressive, both ruthlessly and with no regard for others. Buff is described as a trailblazer, Kyle as a bully-boy.

In the midst of a section justifiably lauding Nick Williams for improving the reporting quality of the Los Angeles Times, for making it more fair, but especially for moving it away from a Republican tilt, he adds literally parenthetically, “(he [Williams] used to say privately that the responsibility of a truly great newspaper was to educate the elite and pacify the masses)” and then moves back to fawning over Williams. That would be a textbook example of burying the lede.

As he starts the section on the Washington Post, he writes:

It was a curious irony of capitalism that among the only outlets rich enough and powerful enough to stand up to an overblown, occasionally reckless, otherwise unchallenged central government were journalistic institutions that had very, very secure financial bases.

Ignoring for the moment that smaller organizations do stand up to our central government on occasion, what’s the actual irony here, and what does capitalism have to do with it?

And when he gets into the Washington Post, his admiration for Phil Graham reasserts itself over his distaste for political journalism. Phil Graham uses his power to be a speechwriter for Lyndon Johnson, to influence politics in ways Kyle Palmer of the Los Angeles Times could only imagine. It’s presented as a great achievement, though a sacrifice because it hurts Graham physically, making him sick from overwork and over-enthusiasm.

And I can’t tell how much sarcasm Halberstam is wielding when he writes:

By chance—and with a certain amount of irony—the Post’s assumption of the role of serious critic of the war coincided with the arrival of Richard Nixon in the White House.

But for all of his biases, Halberstam’s book is massive and detailed. There is one chapter about the New York Times, an entire chapter, presented for the sole purpose of explaining who did not become the editor of the Washington Post. The background was at the Times, not at the Post, and rather than give a short summary he digressed into a history of the New York Times.

Ultimately, the history of American media that Halberstam describes is a loss of balance; a precarious balance and not a very good one, but it did provide competing viewpoints. Balance in American media once meant conservative ownership butting heads with liberal journalists, and a field of reporters who were both liberal and conservative and sometimes something all their own. But over time, the editorial management has been taken over by the journalists, and the pressroom has been insulated from the ownership, who themselves have become chummy with politicians. The old system was flawed, but at least it required that journalists marshal their arguments. Today there is very little balance, and very little marshaling of facts.

The restraints of both papers were being pulled aside; either you trusted your reporters or you were out of the game.

And nobody wants to be out of The Beltway Game.

If you enjoyed The Powers That Be…

For more about The Dream of Poor Bazin, you might also be interested in Release: The Dream of Poor Bazin, Intellectuals and Society, Scoop, The First Casualty, Advise & Consent, For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko, Call Northside 777, The Best of Mike Royko: One More Time, The Tyranny of Clichés, All the President’s Men, World Chancelleries, Liberal Fascism, The Elements of Journalism, Letters to a Young Journalist, Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting, The Vintage Mencken, Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism, A Matter of Opinion, Kolchak: The Night Stalker (TV Series), Front Row at the White House, The Prince of Darkness, The Vision of the Anointed, and The Dream of Poor Bazin (Official Site).

For more about media, you might also be interested in The evolution of news to candy, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, Spin Cycle: Inside the Clinton Propaganda Machine, and The gullible media and the chocolate factory.

- David Halberstam interviews Rick Redfern: G. B. Trudeau at The People’s Doonesbury•

- “I write tomes. Tomes about power. They’re massive books, big, very big, towering best sellers, 750 pages, sometimes more, that’s how big they are. The kind of books about which men like to say ‘I own them.’” This is the start of David Halberstam interviewing Rick Redfern for a new book about press giants.

- The Powers That Be•: David Halberstam (paperback)

- A long and meandering story of how journalists gained the courage to oppose President Nixon.

- Washington Goes to War

- The Washington Metropolitan area’s population increased by over 50% between 1930 and 1941. Another 70,000 arrived in 1942, and 5,000 new federal workers were added every month. The reason was war, and the rumor of war. The book covers the period from 1939 to 1945, with much wandering in between. Part of it is from Brinkley’s personal memories of the period, and much more from interviews.

“There was a wonderful sense of being on the inside and knowing the inside things.”