Mimsy Review: World Chancelleries

Sentiments, ideas, and arguments expressed by famous occidental and oriental statesmen looking to the consolidation of the psychological bases of international peace.

Around the net

Compiled shortly after the devastation of World War One, World Chancelleries• is a plea for peace at any cost. It also sheds light on pre-Second World War viewpoints of progressive outlets like the Chicago Daily News.

| Recommendation | Special Interests Only• |

|---|---|

| Author | Edward Price Bell |

| Year | 1926 |

| Length | 215 pages |

| Book Rating | 5 |

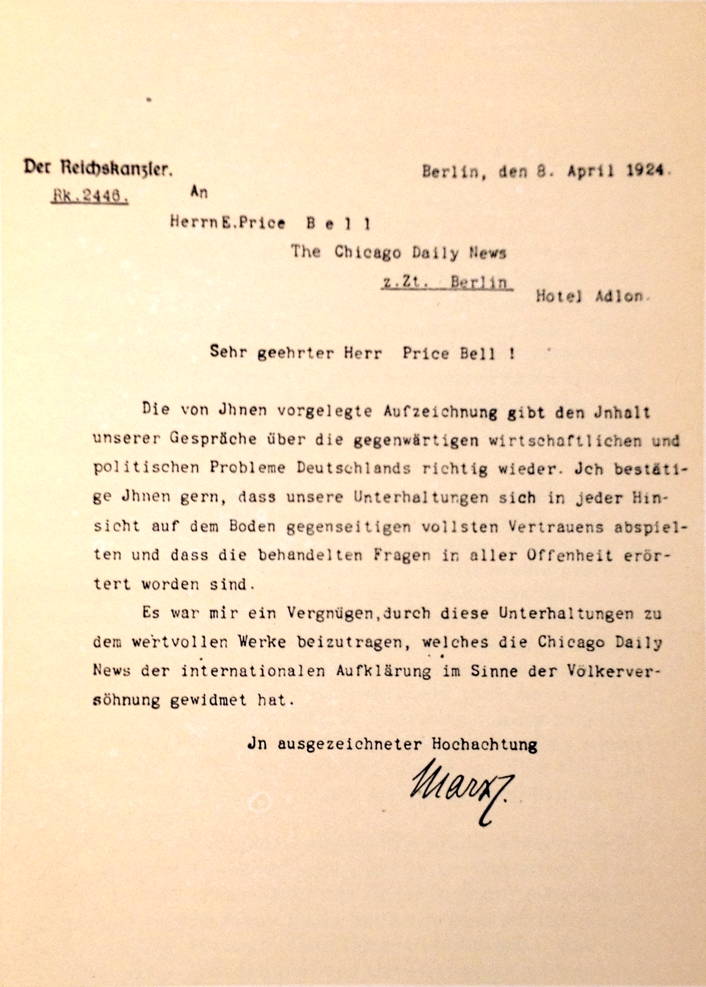

The plaintive thread of these interviews is probably best summarized in this exchange during Edward Price Bell’s interview with Germany’s Chancellor Wilhelm Marx:

“… Heavy wars disarm peoples in their minds; only the abolition of the teachings of war and of the objective symbols of war can keep peoples disarmed in their minds. If we are to abolish war we must forget war. If we are to abolish war we must fill the minds and souls of our young with the gospel, the emotions and the images of peace.”

“Your feeling is that the world’s supreme need is peace?”

“That certainly is my feeling.”

“Do you know of a better way than through a League of Nations to get peace?”

“No.”

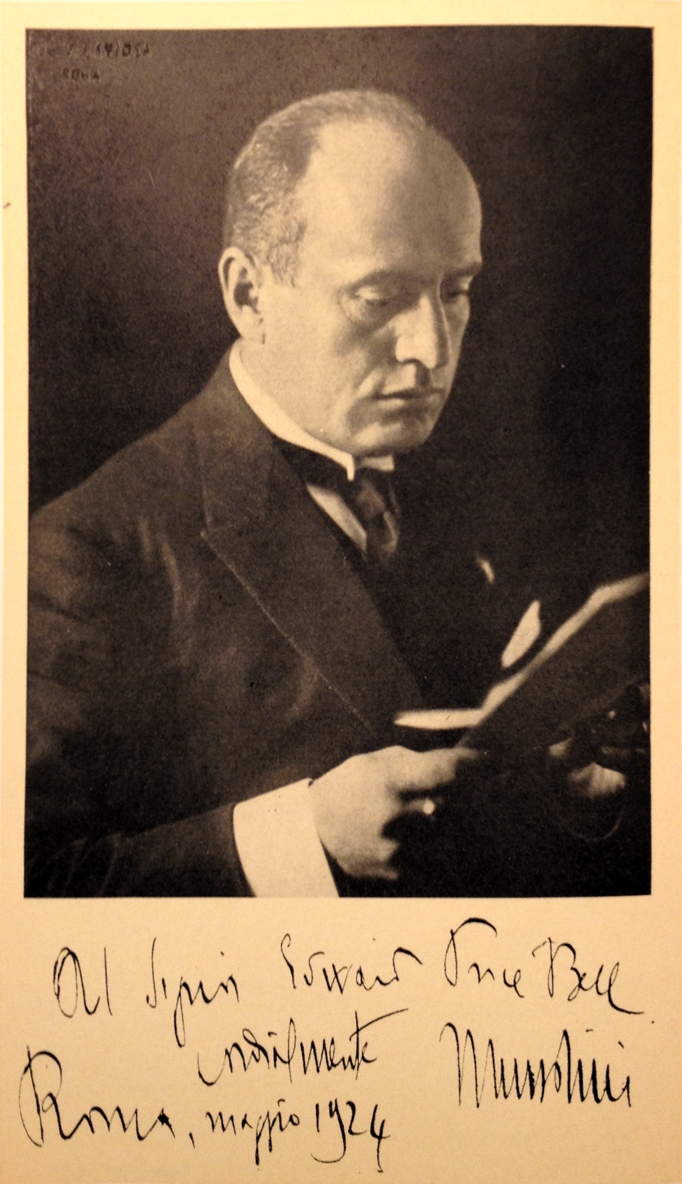

Throughout the book, Bell asks everyone about the efficacy of the League in ways that telegraph what he wants the answer to be. And the opening statement in the above quote, about abolishing the teachings of war, is reproduced as the frontispiece quote to this interview. Similarly, the Italy interview has Mussolini’s quote about creating a new Italian pulled out for emphasis:

“Fascismo is the Greatest Experiment in Our History in Making Italians.”

And in the China interview, Dr. Tang Shao-Yi argues that…

“Education is the specific for the disease of war, and education works slowly. We must teach our children that to kill in war is precisely as criminal an act as to kill in civil life. Murder is murder. We loathe murderers. People must understand that war killers are murderers.”

The importance of education by the right people is affirmed in Bell’s introduction:

Not only statesmen, but specialists and thinkers of every calling, have a natural allegiance with the interviewer for the education of mankind. Fame is power. Fame is responsibility. Names with hypnotic properties are obligated to kindle, enlighten, and direct an attentive world.

World Chancelleries• was published in 1926, and edited by Edward Price Bell, the “Dean of the Foreign Staff of The Chicago Daily News.”

This is an odd book all around. I first found it at a library book sale. I used to work at the University of San Diego, and saw it at their Copley Library discards sale for seventy-five cents. It appears to have arrived there after having been presented by the Chicago Daily News to a Mr. M.L. Hallett.

As a contribution to the cause of world peace, these interviews, originally published in The Chicago Daily News, are here compiled in permanent form in a limited complimentary edition, of which this copy is Number 7985.

Hallett gave it to his “Most Capable Assistant” Cecil Angelo Maggi, an artist and Los Angeles teacher who presumably donated it to the San Diego College for Women, which merged later to become the University of San Diego, where I found it.

Interestingly, while Maggi has minor fame as an artist I can find no reference to Hallett, however important he may have been in world peace circles in 1926. There was in 1901 a Massachusetts advertiser Mr. M.L. Hallett who studied in Chicago, and it makes sense that an advertiser might have an artist as an assistant, but I have no idea if this is the same person, or whether he was presented this copy for his own contributions to world peace or because he had subscribed to the publication in some way.

Throughout the book, the interviewees affirm the peaceful desires of all of the major players on the world stage, from France to Italy to Japan to China.

Italy’s peaceful nature is affirmed by Benito Mussolini, and Japan, we are assured, has no need or desire whatsoever for Guam or the Philippines.

In his introduction, Bell quotes his publisher, Victor Fremont Lawson:

“All nations, rightly studied, are likable,” was one of Mr. Lawson’s sayings.

It is important, I think, not to fault them too much—after a war such as World War I it is natural to cling to a desperate hope that war is over for good. But the level of self-deception prevalent throughout these interviews also cannot be downplayed. It is very likely that the desire throughout the work for strong leaders who can control their nations’ warlike desires, and the propaganda produced on behalf both of such leaders and of convincing the public that conquest was the furthest thought from all minds itself contributed to the climate of naive, desperate accommodations that produced World War II.

It was the support for governments abolishing some points of view as beyond the pale that allowed for the evils of Nazi Germany.

Also in his introduction, there was apparently some attempt by warmongers to fortify Hawaii against Japanese aggression around the time he was performing these interviews. Fortunately, the peace statements of world leaders assuaged our fears:

As to the Pacific Ocean, The Daily News found it enveloped in war-fog and left it clear… People smiled at the thought of a “new Hawaiian Gibraltar in the Pacific.” Japan was not creeping up on the Philippines and Guam… It all had been a dyspeptic dream!

The Daily News also pronounced Ramsay MacDonald as the herald of world peace:

His name will be written boldly in political history as that of a man during whose term of office the final steps toward a durable peace were taken by the Great Powers of Europe.

Not the first steps, but the final steps, to durable peace. The two native Philippine interviews also emphasize that there is no danger to the Philippines that some foreign power, including especially Japan, poses them a threat.

Once you get past the desperate attempt to make all world leaders likable, and their warlike actions peaceable, these are interesting interviews. In the first interview, German Chancellor Wilhelm Marx1 describes the government’s attempts to alleviate overcrowding and the subsequent rise in the cost of housing: Germany…

“…drastically restricted rents, and this restriction operated against house construction…”

They tried to tax “the wealthier classes” to build more; people with multiple rooms were forced to accept lodgers at the restrictive rents. But—

“These authorizations mean that the matter covered by them was carefully read and formally approved for publication by the officials interviewed. Also, in most instances, the statements were sanctioned by the Cabinets concerned, thus acquiring the literal authenticity and moral authority of great State papers.”

“…this kind of administration had the tendency to lead to corruption. Socialism in this realm failed us.”

But that doesn’t mean socialism elsewhere was faulted.

“Opportunities shall be provided by law equalizing the advantages, bodily, mental, and social, of illegitimate children with those of legitimate children. Every care will be taken to promote in every practicable way the vigor, sanity, and happiness of the rising generation.”

This followed a section on safeguarding the family. I don’t know what it means in that context. But they also enforced freedom of religion by using government monies to fund churches:

“We have no State Church, but levy taxes for the support of all creeds and denominations in accordance with their numerical strength. These taxes enable the various religious bodies to devote all of their collections to the charities of their choice.”

It’s no wonder the Nazis were able to silence the churches when they took power—the government could directly cut off their funds!

But the most intense interview is his interview in Italy with Benito Mussolini, “…the forceful apostle of Fascismo…”. That was from the Daily News’s Rome Correspondent Hiram Kelly Moderwell. Now, Moderwell is known to have criticized the fascists, but here he shows none of it, describing Mussolini’s “musical and brilliant Italian… his fine eyes sometimes gleaming playfully…”.

But this is nothing compared to Bell’s descriptions:

“Those who see mental and moral rather than physical features will, I think, call him handsome.”

“Mussolini… has become a portent and a promise in the civilization of the world.”

“They call him dictator. To the unpatriotic, to the anti-social and anti-civilized, to the lawless, to the bolshevists, he is dictator. To Italy—full of sterling human worth—to Italy, in my judgement, Mussolini is liberator.”

Bell praises all of his interview subjects, but nowhere as effusively as he praises Mussolini.

Mussolini and Ramsay MacDonald, then the Socialist-Labor Prime Minister in Britain, echo themselves when they talk of their philosophies. Consolidation of power under the state is not an enemy of liberty; it is true liberty.

Mussolini says:

“…Fascismo is not an enemy of true liberty. It is an enemy of false liberty. It is an enemy of the liberty of one person or of any group of persons to take way the liberty of another person, or of the nation as a whole. Our point of view is that when we assert the rights of society we are asserting the rights of every member and of every element belonging to that society. No individual rights or liberties are secure in a State whose national rights and liberties are not secure. Upon social justice rests all justice; social justice is essential to social equilibrium; and social equilibrium is another name for civilization.”

MacDonald says:

“Socialism is for real, not fictitious liberty. Personal liberty of the real sort can come in no way except through a scientific social organization…”

They also both talked of their politics as spiritual politics. Mussolini called his Fascismo…

“… a thing of the soul, and a thing of practical politics. It is emotion, theory, and practice; it is sentiment, ideas, and acts; it is something felt, something thought, and something done. Fascismo is a spiritual inspiration, a body of doctrine, and a system of State policy.”

MacDonald used the same language to describe socialism:

“In the domain of emotion, of conscience, in the spiritual domain, Socialism is a religion of popular service—a deep enthusiasm for the physical, mental, and moral well-being of the human family. In the domain of intellect, of thought, of theory, it is a scientific program of social betterment.”

And when asked if socialism is anti-Christian, MacDonald replied:

“On the contrary, it is based on the Gospels. It signifies a reasoned and resolute effort to Christianize government and society.”

Throughout these books, Bell and his subjects decry “bolshevism” and “the bolshevist” but this does not indicate a lack of love for socialism. Daily News correspondent then in England, Hal O’Flaherty, describes MacDonald’s interview by calling socialism a universal solution for civilization:

Americans who read carefully and digest this amazingly clear exposition of Socialism must be impressed with its universality; for it not only brings to the light the desires of men and women here in England, Scotland, and Wales, but expresses much of the longing for better social and political conditions in every civilized community.”

Oddly, while these interviews were heavily edited, sent back and forth between interviewer and interviewee (imprimaturs from each interviewee appear in facsimile in the book, assuring the reader that they approved the interview), contradictions did appear. MacDonald, for example, assures Bell that “We have no notion of running British industry from Whitehall.” But a page later, we see the following exchange:

“Do you still hold, as you did in 1913, that nationalization of lands, mines, and railways is the best means of curing social unrest in England?”

“That is the next stage in evolution.”

The China interviews include a different kind of contradiction. The Chinese love peace so much that they endure “generations of foreign imposition and cruelty” without serious rebellion. But they also are a check on the designs of their warlords:

“Let no one infer from our war lords that the Chinese people like war lords. Observe this tiger skin on the floor. It once clothed a free-ranging and ferocious beast in the first, but finally this beast fell a victim to the hunter and was skinned. Our ruling generals are ranging somewhat freely at the moment. But they must be wary. Not one of them dares to go home. Not one of them would be safe at home. In this fact and in many others we have proof that the democratic heart of China is sound.”

China, he goes on to say,

“… is too great to worship the sword. Its power is the power of weakness, not of strength; only the weak need the sword.”

But to rid the world of swords, it follows—but is neither said nor questioned here—is to promote the rule of the strong over the weak. This is, ultimately, their solution for peace: strong leaders at the top of collectivist governments who “direct an attentive world” at the “physical, mental, and moral” levels.

Peace should not be so highly prized as that.

No relation, as far as I can tell, to Karl Marx.

↑

If you enjoyed World Chancelleries…

For more about The Dream of Poor Bazin, you might also be interested in Release: The Dream of Poor Bazin, Intellectuals and Society, Scoop, The First Casualty, Advise & Consent, For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko, Call Northside 777, The Best of Mike Royko: One More Time, The Tyranny of Clichés, All the President’s Men, Liberal Fascism, The Elements of Journalism, Letters to a Young Journalist, Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting, The Vintage Mencken, Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism, A Matter of Opinion, Kolchak: The Night Stalker (TV Series), Front Row at the White House, The Prince of Darkness, The Vision of the Anointed, The Powers That Be, and The Dream of Poor Bazin (Official Site).

For more about fascism, you might also be interested in A direct line to the Charlottesville riots… from 1938, Why now for the alt-right?, Liberal Fascism, and Eugenics and Other Evils.

For more about peace, you might also be interested in Peace is a deal.

- Edward Price Bell at Wikipedia

- “Edward Price Bell (March 1, 1869 – 1943) was a Chicago journalist, best known for his work with the Chicago Daily News.”

- Victor Fremont Lawson at Wikipedia

- “Victor Fremont Lawson (September 9, 1850 – August 19, 1925) was an American newspaper publisher who headed the Chicago Daily News from 1876 to 1925. Lawson was president of the Associated Press from 1894 to 1900, and was on the board of directors from 1900 to 1925.” “[The Chicago Daily News] was quintessentially an urban newspaper, committed to private business but also to activist government, to social welfare, and to the broad public life of the city. It was a progenitor of the kind of progressive reform politics that came to flower in many cities during the early twentieth century.”

- World Chancelleries•: Edward Price Bell (hardcover)

- “Sentiments, ideas, and arguments expressed by famous occidental and oriental statesmen looking to the consolidation of the psychological bases of international peace,” this is a book of original interviews with world leaders in 1925, from Wilhelm Marx of Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy, to lesser known Philippine, Japanese, and Chinese leaders.

- World Chancelleries

- A collection of interviews in 1924 and 1925 with an aim toward world peace.

I am in the process of putting World Chancelleries online. I’ve checked the copyright renewal databases at Stanford and at Gutenberg and its copyright does not appear to have been renewed in either 1953 or 1954. As I write this, I have the Italian and German interviews already online, and the British (Ramsay Mac Donald Socialism) interview should be up in a few days.