Mimsy Review: All the President’s Men

That heady era of good feeling, in which reporters had rubbed elbows and shoulders with President Kennedy’s men in touch football and candlelit backyards in Georgetown and Cleveland Park, was a thing of the past.

Around the net

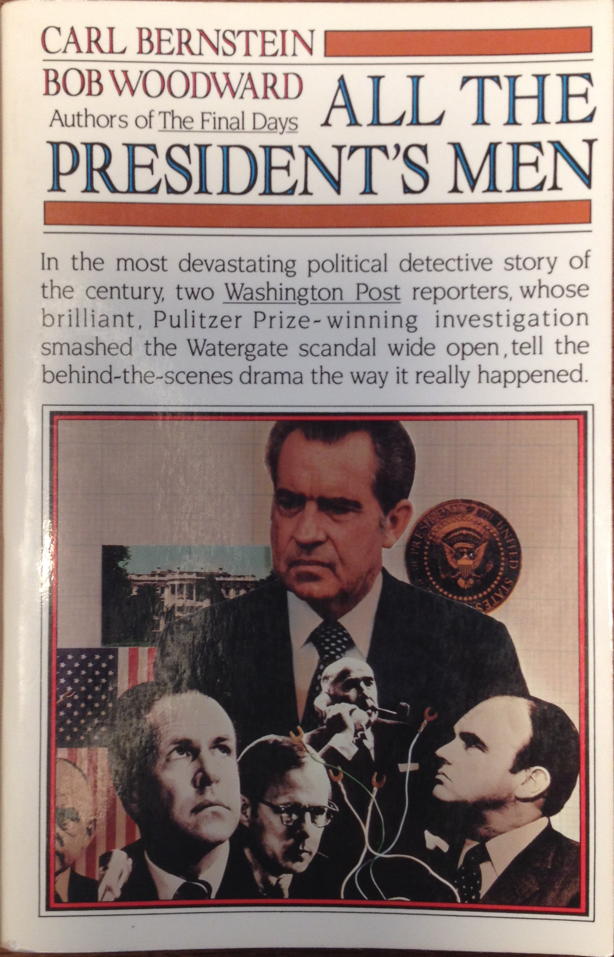

Supposedly written because Robert Redford wanted to base a movie on the book, this is a great memoir of two journalists wondering what the hell was up after a failed burglary on an office in the Watergate Building.

| Recommendation | Worth reading• |

|---|---|

| Authors | Carl Bernstein, Bob Woodward |

| Year | 1974 |

| Length | 345 pages |

| Book Rating | 7 |

There is probably no event more foundational to the modern journalist’s self-image than that of Woodward and Bernstein at the Washington Post, shoe-leathering out the connections between a failed burglary and the President of the United States. All the President’s Men• is an engaging and workmanlike look at what kind of shoe leather and stratagems were necessary (and what were, sometimes, unnecessary and, in retrospect, unreasonable) to get at the facts of the case: how the Committee to Reelect the President, with the explicit authority of President Nixon, broke some of the basic laws of both the country and general decency in order to ensure the reelection of the President and then to cover up their actions.

It’s a powerful story, and has entered the cultural lexicon mainly through the movie based on it.

One of the first things that struck me while reading the book is that the movie followed the book fairly accurately. Reading it after seeing the movie, it’s obvious when entering a section that made it into the film. Obviously the film had to cut stuff, and move a few things around, but what it kept, it didn’t significantly change.1

The other thing that struck me is just how deeply Woodward and Bernstein’s story have entered the national consciousness. Early in the book, describing how the Post works, they write:

The invariable question, asked only half-mockingly of reporters by editors at the Post (and then up the hierarchical line of editors) was “What have you done for me today?” Yesterday was for the history books, not newspapers.

That line was used verbatim when Jerry Hathaway discusses Chris Knights shortcomings in the great Real Genius•.2

There are also some good tricks in here for investigative journalism. For example, the Washington Post had printed that one of the bugging participants had not yet been disclosed and had been granted immunity. Bernstein didn’t know who it was, but one of the Committee to Reelect the President (CRP) people he was trying to get information from thought he did. She kept guessing names. Bernstein, rather than let her know he didn’t know, just kept saying, no, it wasn’t him, and was able to then get the names of people this person thought it might be.

The book also demonstrates the usefulness of having a layer of editors between writers and management:

The day after the election, Bradlee and Simons asked Sussman for a memo advising how Bernstein and Woodward intended to pursue their investigation and listing areas on which they intended to concentrate…

Woodward was demonstrably angered at the request. Not without a touch of arrogance, Bernstein and he advised Susan to write a memo for the editors saying any damn thing that came into his head.

Sussman wrote a one-page memo which concluded: “Woodward and Bernstein are going back to virtually every old source and some new ones who have shown an interest in talking now that the election is over. Some of our best stories to date were pretty much unexpected and did not come from particular lines of inquiry, and quite possibly the same will be true now.”

In some cases, they let their side3 off the hook for things that probably would be considered a lead for a good story if it were the target of their investigation. For example,

The chief prosecutor [Silbert] was a registered Democrat and his wife, an artist, had been a volunteer in the McGovern campaign. She had used her maiden name so that there would be no unfair connection made between her political activities and the prosecution of the Watergate case.

McGovern had been the most recent candidate running for President against Nixon, whose reelection team Silbert was prosecuting. It seems to me that a different prosecutor would have been a good idea, though, given what’s been going on in Wisconsin some people do think otherwise.

As the CRP started to put some heat on the Post, Bernstein discovered a novel means of getting a source: let yourself be served with a subpoena. CRP issued subpoenas for several people at the Post, including Bernstein.4 Bradlee told Bernstein to hide until they could talk to their lawyers and decide on the best way to be served. He went to see Deep Throat—the movie, not the source—and when the Post’s lawyers figured things out they had Bernstein return to the Post and wait to be served.

When the server came, Bernstein was working on a story, and,

Head down, Bernstein raised one hand and picked of the subpoena. But the page stood there silently. Finally, Bernstein glanced up from the typewriter. The page looked about 21, tousled blond hair, wearing a V-necked sweater, very collegiate.

“Hey, I really feel bad about doing this,” he said. “They picked me because they thought somebody who looked like a student could get upstairs easier.” He was a law student who worked part-time at the firm headed by Kenneth Wells Parkinson, the chief CRP attorney. He promised to keep alert for any information that might be useful to the Post and gave Bernstein his home phone number.

The authors don’t say whether this potential source generated any leads. In general, they are very good about not identifying sources that did not want to be identified.5 This has the tendency to amplify the contributions of those who are okay about being identified, such as Hugh Sloan. Sloan comes off very well here, as, I think, the only identified high-level employee of CRP to resign because he was uncomfortable with what CRP was doing.

A lot of this is journalism that doesn’t get done nowadays, except fictionally in journalistic thrillers. Ben Bradlee, the executive editor of the Washington Post at the time, seems to have let Woodward and Bernstein focus exclusively or nearly exclusively on the Watergate case. It’s hard to imagine a modern newspaper letting two of their employees stick with a single story for two years.

The book ends, for the most part, on the discovery of Nixon’s White House taping system and the missing 18½ minutes—their final, 3 page chapter after the tapes are discovered simply summarizes, I suspect, things that happened since sending the book to their publisher.

That final chapter ends with their highlighting Nixon vowing not to resign, as if they knew he’d be forced to do just that. In those days, the reporters, I suspect, could be sure that erasing their communications doomed any chances to remain as president. It assured either impeachment or resignation.

Reading this, it occurs to me that conservative Republicans must in retrospect be relieved that Nixon got caught in the Watergate scandal. Without Watergate, Nixon—wage-fixing, price-fixing Nixon—would have become a liberal hero, the Republican that all other Republicans would have been expected by the press to emulate.

If you are at all interested in journalistic history, and you haven’t read this book yet, you should. It has a reputation for being dry, but I disagree. It’s a well-written tale of how they built their story from interviews, research, and a determined cultivation of sources.

You might think that, of course it didn’t, this stuff really happened. They can’t change it. I would only say that if you feel that way you haven’t seen too many movies based on real life!

↑The canonical phrase would appear to be What have you done for me lately?, but Real Genius• uses the Post form of the phrase.

↑That is, the side investigating the scandal rather than the side trying to cover it up.

↑Woodward was named as well, but he was out of town when CRP tried to serve the subpoenas.

↑Including, in a footnote, implying that they had no high-level FBI sources, when, in fact, Deep Throat was Mark Felt, the number two man at the FBI.

↑

If you enjoyed All the President’s Men…

For more about The Dream of Poor Bazin, you might also be interested in Release: The Dream of Poor Bazin, Intellectuals and Society, Scoop, The First Casualty, Advise & Consent, For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko, Call Northside 777, The Best of Mike Royko: One More Time, The Tyranny of Clichés, World Chancelleries, Liberal Fascism, The Elements of Journalism, Letters to a Young Journalist, Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting, The Vintage Mencken, Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism, A Matter of Opinion, Kolchak: The Night Stalker (TV Series), Front Row at the White House, The Prince of Darkness, The Vision of the Anointed, The Powers That Be, and The Dream of Poor Bazin (Official Site).

For more about journalism, you might also be interested in Kolchak: The Night Stalker (TV Series), All the President’s Men, Call Northside 777, The President’s freelancers, Confirmation journalism and the death penalty, Fighting for the American Dream, Mike Royko: A Life in Print, The World of Mike Royko, Fit to Print: A.M. Rosenthal and His Times, A Reporter’s Life, Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism, Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting, Letters to a Young Journalist, The Elements of Journalism, The First Casualty, Scoop, Release: The Dream of Poor Bazin, and Are these stories true?.

For more about Richard Nixon, you might also be interested in Dick and The Palace Guard.

For more about Richard Nixon, you might also be interested in Should we be pessimistic about good governance going into 2016? and The Palace Guard.

For more about Watergate, you might also be interested in Dick, All the President’s Men, and The Palace Guard.

- All the President’s Men•: Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (paperback)

- “Beginning with the story of a simple burglary at Democratic headquarters, Bernstein and Woodward kept the tale of conspiracy and the trail of dirty tricks and dark secrets coming—delivering the stunning revelations and pieces in the Watergate puzzle that brought about Nixon's scandalous downfall. Their explosive reports won a Pulitzer Prize for The Washington Post and toppled the President. This is their book that changed America.”

- All the President’s Men

- Probably one of the most influential events in journalism history made into one of the best films of the seventies.

- Bob Woodward

- “Bob Woodward has worked for The Washington Post since 1971. He has won nearly every American journalism award, and the Post won the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for his work with Carl Bernstein on the Watergate scandal. In addition, Woodward was the main reporter for the Post’s articles on the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks that won the National Affairs Pulitzer Prize in 2002. Woodward won the Gerald R. Ford Prize for Distinguished Reporting on the Presidency in 2003. The Weekly Standard called Woodward ‘the best pure reporter of his generation, perhaps ever.’”

- Carl Bernstein

- “Co-Winner of the 1973 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.”

- Chris meets with Jerry—Real Genius at Real Genius•

- Jerry Hathaway dresses down Chris Knight for distracting the team.

- Firing Line: The Limits of Journalistic Investigation at The Firing Line Archive

- From Firing Line, with William F. Buckley Jr., July 9, 1974, with Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward.

- Real Genius•

- A movie about college kids that didn’t dumb down college to get its laughs. One of my favorite movies.

- Richard Nixon

- “Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913 – April 22, 1994) was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961.”

- The Watergate Story at The Washington Post

- A timeline of the Watergate story at the Washington Post, with links to the relevant articles.

- What have you done for me lately?: Garson O’Toole

- “The Google Books Ngram Viewer for the shortened phrase ‘you done for me lately’ shows a flat line (roughly zero) until the early 1940s and then a rapid ascent up until the 1970s. There is a dip in the late 1980s and then another ascent.”