Mimsy Review: The Prince of Darkness

“It would be hard for today’s ultraserious journalists to imagine what fun it was on the campaign circuit then. A poker game most nights, and drinking around the clock. Everybody started the morning with a Bloody Mary. Near the end of the trip when Eastern Airlines ran out of vodka, reporters nearly rioted. Flight attendants solved the problem by mixing the Bloody Marys with gin. Nobody complained.”

Around the net

Robert Novak’s memoir covers his life from 1957 working for the Associated Press, through his 30-year partnership with Rowly Evans, and is bookended by the Plame affair. It’s very engaging, making you feel as much an insider as he dared as a conservative writer in a congenitally liberal town.

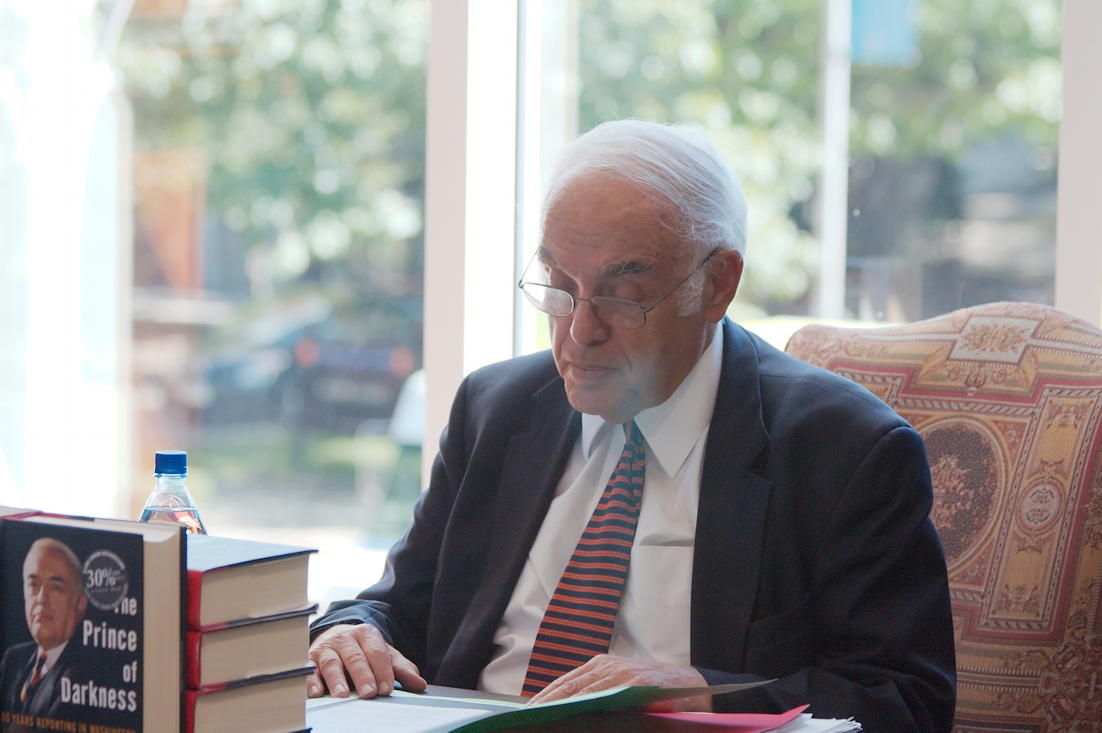

The Prince of Darkness talking about his book, September 13, 2007. (Photograph taken by Dori (dori@merr.info), CC-BY-3.0)

Of all of the memoirs I’ve read for the tDoPB project, The Prince of Darkness• made me most want to meet the author. He gets his name from his supposedly pessimistic personality, though it doesn’t show through in the book, at least toward the end. And, while Novak doesn’t say it, it appears that it partially comes from his “swarthy” appearance. Back in the 1968 Humphrey campaign, Rolling Stone reporter Tim Crouse wrote that Novak was

…short and squat, with swarthy skin, dark gray hair, a slightly rumpled suit, and an apparently permanent scowl. He kept his hands in his pockets and looked at the floor. Some of the other reporters pointed him out and whispered about him almost as if he were a cop come to shush up a good party.

“Novak looks evil,” said a gentle, middle-aged Timesman.

Novak talks about the early years on the campaign beat as a blast, “a poker game most nights, and drinking around the clock.” But you certainly can come out this book thinking that life sucks in DC. Friendships do not easily survive this town in Novak’s telling. Sometimes it has to happen: when there’s a special prosecutor looking into who you talked to and what you said to them, the person you actually did talk to is probably going to be under orders from their lawyers not to add to the list (Karl Rove).

Others are less necessary, such as co-workers who either disagree with your politics or who choose to use your misfortune to further their standing (James Carville).

I have also learned that there are two kinds of restaurants in DC: restaurants where you want to be seen, and restaurants where you do not want to be seen. The former are divided into those frequented by lobbyists and politicians, and those frequented by journalists and politicians. When Rowly Evans wanted to talk to Novak about doing a column together,

He picked Blackie’s House of Beef, an inexpensive steak house frequented by government workers. For one of Washington’s upscale journalists to pick such a downscale place suggested he did not want us to be seen by anybody he knew.

Some of the book is pure DC history. For example, Novak commonly took sources to the wonderfully-named Sans Souci, a moderately upscale French restaurant. It is now a McDonald’s, according to Novak. It was five minutes from the White House, a perfect place to talk to White House staffers and other political leakers. One of the sources he took there was Jeb Magruder, who was performing a Nixonian “planned leak” operation during the Watergate scandal.

Years later, one of Mitchell’s aides told me how irritated CREEP bean counters were by the pricey expense accounts submitted by Magruder for our Sans Souci lunches. This aide was surprised when I informed him that I had paid for all of Magruder’s meals.

During Watergate, Novak leaked the initial news about the missing eighteen minutes, sourced apparently from the special prosecutor’s press secretary, James Doyle•. I say apparently, because the information comes from this one-level-too-cute paragraph:

The Evans & Novak column of November 26 contained one of my most important Watergate exclusives… eighteen minutes had been erased from the critically important tape recording… In his book•, Jim Doyle did not speculate how I so quickly obtained all this inside information. He certainly did not finger himself as the source, and—from the distance of thirty years—neither shall I. In the interest of full disclosure, however, I find that my 1973 expense account record shows that on Friday, November 23, I lunched with Jim Doyle at Sans Souci. My records show lunch that day cost me $18.19 ($82.88 in 2007 dollars). The total indicated that Jimmy and I enjoyed more than one drink apiece. I then could shake off a couple of Scotches and a beer to write cogent copy. I left Sans Souci at about two p.m. to walk across the street and write a column containing my scoop.

After Nixon, Carter thought he could use Novak to get around potential scandals. Carter has a reputation as being a nice guy completely out of his depth as President. Novak portrays him as “a habitual liar who modified the truth to suit his purposes.”

Evans & Novak documented several of Carter’s fibs—things like making up past meetings with important people and making up relationships. Carter then met with Novak and lied about the contents of their meeting, saying that Novak had apologized for the column!

Perhaps because of this, and because he was moving to the right, Republican Presidents had a tendency to think him on their side—until he started reporting on them.

He had a tendency to go to news-making events without invites. Reporters weren’t allowed in polling places, at least in Illinois in 1968, so Novak signed up for poll-watcher credentials, and got in to a polling place on Chicago’s West Side. He was able to see vote fraud up-close:

A nod from the Democratic precinct captain allowed an unregistered voter to vote by merely signing an affidavit. Whether he might vote in another precinct as well would be impossible to determine…

Without asking whether the voter wanted help, the election judge… entered the booth with every voter and instructed him to pull the Democratic straight-party lever, breaking the state law.

Once the curtain had closed and the voter was alone inside the booth, the judge would hover just outside so that the vote was anything but secret.

Then, at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, he noticed that organized labor was about to hold a meeting—and wasn’t paying close attention to who walked in.

In those days before I was a regular television performer, I was not recognized and did not pay attention to my personal appearance. Wearing a wrinkled sports jacket with no tie and needing a haircut, I at age forty-five could pass for a labor skate. With close to three hundred people in the room, I unobtrusively took a seat in the rear.

Christopher Lydon, a New York Times reporter, also wanted in, but the union official at the door wasn’t letting him in. So Lydon pointed out that they had already let one reporter in. Which meant that Novak got kicked out, too.

His life, in some ways, was like a movie. He gets lots of telephone calls from near-strangers asking him to meet, in front of his house, at various restaurants, in fast cars. He went to Nicaragua during a civil war, and jumped from an airplane at seventy-two.

And, back in 1972, Bill Sullivan, a former “number three official in the Federal Bureau of Investigation” told him, at lunch, that “I probably would read about his death in some kind of accident but not to believe it. It would be murder.”

Four years later, Sullivan was shot while hunting in New Hampshire; it was ruled an accident, and Sullivan’s co-writer said that both he and Sullivan’s family believed this.

Part of being a good journalist is knowing who to trust. Novak gave examples of trusting sources he shouldn’t have—and knew in his gut he shouldn’t have—during the Watergate scandal. In the months leading up to the presidential election of 1976, he gives an example of not trusting a source he knew in his heart was trustworthy and close to the action: Maureen Reagan. Ronald Reagan’s daughter told him that Reagan was running, and not to believe anyone who said otherwise—even Reagan himself. Novak chose not to follow that advice, and so lost out on a good story.

At the start of the 1984 campaign, Pat Caddell told him that Gary Hart would take New Hampshire.

Trusting shrewd political analysts such as Caddell often put me ahead of the pack in predicting political outcomes. This time I flinched. In my February 27 column the day before the primary, the best I could do was a super-cautious forecast that Hart “could well pass Glenn, surpass 20 percent and keep Mondale below 30 percent.

Just as Caddell predicted, Hart won New Hampshire—easily, with 39 percent to Mondale’s 27 percent.

Novak watched journalism grow more and more stridently left. Perhaps the turning point in alienating Novak from the anointed in Washington culture was when Evans and Novak wrote about Marxist revolutionary Orlando Letelier’s written desire to “[make] propaganda for American socialism…”. The Washington Post and the Boston Globe called it McCarthyesque and refused to publish the column. The Boston Globe started using their columns much less frequently after that, and their relationship with the Post also deteriorated.

If I had to do it all over again, would I have just ignored the file folder brought me by John Carbaugh and saved myself all these troubles? There are some columns I wish I had not written, but not these. The canonization of a Marxist-Leninist revolutionary by our colleagues in journalism was their problem, not ours. Nevertheless I felt more alienated after those events from the mainstream of Washington journalism.

During the Reagan years, they criticized the Reagan White House for not always living up to their ideals. This was not uncommon for journalists then; it certainly isn’t today. What was uncommon was for journalists to try and pull politicians to the right instead of to the left.

We were being criticized for what columnists do. The real complaint with us is that we were taking conservative positions.

It isn’t politics until someone questions the status quo. Then that person is injecting politics into the discussion. The status quo among the media, then as now, is leftist.

The Prince of Darkness• covers Novak’s political journey to the right as well as his spiritual journey to Catholicism. And along the way it also describes DC’s political and spiritual journey to the left. And it’s well-written. It’s a fascinating perspective.

If you enjoyed The Prince of Darkness…

For more about The Dream of Poor Bazin, you might also be interested in Release: The Dream of Poor Bazin, Intellectuals and Society, Scoop, The First Casualty, Advise & Consent, For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko, Call Northside 777, The Best of Mike Royko: One More Time, The Tyranny of Clichés, All the President’s Men, World Chancelleries, Liberal Fascism, The Elements of Journalism, Letters to a Young Journalist, Inside the Beltway: A Guide to Washington Reporting, The Vintage Mencken, Deadlines & Monkeyshines: The Fabled World of Chicago Journalism, A Matter of Opinion, Kolchak: The Night Stalker (TV Series), Front Row at the White House, The Vision of the Anointed, The Powers That Be, and The Dream of Poor Bazin (Official Site).

- The Prince of Darkness•: Robert D. Novak (paperback)

- The Prince of Darkness, besides being a memoir of Bob Novak’s life as a journalist, is also an engaging history of journalism and politics in the nation’s capital.

- Not Above the Law•: James Doyle

- “The Battles of Watergate Prosecutors Cox and Jaworski—A Behind-the-Scenes Account”. James Doyle was a Special Assistant to Water prosecutors Archibald Cox, Leon Jaworski, and Henry Ruth.