Mimsy Review: Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave

I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason. He must be able to detect no inconsistencies in slavery; he must be made to feel that slavery is right; and he can be brought to that only when he ceases to be a man.

Around the net

Not only does slavery make life worse for slaves, it doesn’t make life better for slave-owners. And the ultimate freedom is freedom to learn.

| Recommendation | Read now• |

|---|---|

| Author | Frederick Douglass |

| Year | 1846 |

| Length | 158 pages |

| PDF Rating | 8 |

In the beginning of Frederick Douglass’s• Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave, he writes about growing up as a slave and not really having a family:

I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.

Douglass didn’t know his own birthday: slavers deliberately tore out of their slaves any sense of history or future by splitting up families.

And also by encouraging living in the moment rather than planning for the future. One of his masters said so explicitly:

He told me, if I would be happy, I must lay out no plans for the future, and taught me to depend solely upon him for happiness.

On holidays, they were expected to spend their time in celebration—mainly, getting drunk. While some of them spent their holiday time building up their living quarters or putting away meat in hunting,

By far the larger part engaged in such sports and merriments as playing ball, wrestling, running foot-races, fiddling, dancing, and drinking whisky; and this latter mode of spending the time was by far the most agreeable to the feelings of our masters. A slave who would work during the holidays was considered by our masters as scarcely deserving them. He was regarded as one who rejected the favor of his master. It was deemed a disgrace not to get drunk at Christmas…

Slaves, when questioned, reported themselves happy—in just the way that Natan Sharansky reported in The Case for Democracy about people under dictatorships:

It is partly in consequence of such facts, that slaves, when inquired of as to their condition and the character of their masters, almost universally say they are contented, and that their masters are kind. The slave-holders have been known to send in spies among their slaves, to ascertain their views and feelings in regard to their condition. The frequency of this has had the effect to establish among the slaves the maxim, that a still tongue makes a wise head. They suppress the truth rather than take the consequences of telling it, and in so doing prove themselves a part of the human family. If they have any thing to say of their masters, it is generally in their masters’ favor, especially when speaking to an untried man.

The comparisons they make in their lives tends to be between what they know; there is little concept of what could be under freedom.

I always measured the kindness of my master by the standard of kindness set up among slaveholders around us. Moreover, slaves are like other people, and imbibe prejudices quite common to others. They think their own better than that of others. Many, under the influence of this prejudice, think their own masters are better than the masters of other slaves; and this, too, in some cases, when the very reverse is true… They seemed to think that the greatness of their masters was transferable to themselves. It was considered as bad enough to be a slave; but to be a poor man’s slave was deemed a disgrace indeed!

Slaves competed to be trusted by slave-owners, because they wanted the perks of being treated well. One of the best jobs on the plantation that Douglass worked at was bringing deliveries among the various locations that made up the holdings of the slave-owner. It meant traveling instead of working in the fields. In an odd turn of phrase, Douglass compared slaves to politicians seeking to “please and deceive” voters:

The competitors for this office sought as diligently to please their overseers, as the office-seekers in the political parties seek to please and deceive the people. The same traits of character might be seen in Colonel Lloyd’s slaves, as are seen in the slaves of the political parties.

Slavery, of course, attracted people who preferred slavery, on both sides. About one of the overseers, the aptly-named Mr. Gore, “proud, ambitious, and persevering” and “artful, cruel, and obdurate”:

He was just the man for such a place, and it was just the place for such a man.

Once an overseer made an accusation, punishment must always follow, regardless of truthfulness, never using words where the whip would answer as well. Gore once shot a slave for running into the water during a whipping.

Douglass emphasizes how pointless all this was. When he escaped to freedom, he was both surprised and disappointed to find that slavery does not even enhance the lives of slave-owners:

I had very strangely supposed, while in slavery, that few of the comforts, and scarcely any of the luxuries, of life were enjoyed in the north, compared with what were enjoyed by the slaveholders of the south… I had somehow imbibed the opinion that, in the absence of slaves, there could be no wealth, and very little refinement. And upon coming to the north, I expected to meet with a rough, hard-handed, and uncultivated population, living in the most Spartan-like simplicity, knowing nothing of the ease, luxury, pomp, and grandeur of southern slave-holders…

…But the most astonishing as well as the most interesting thing to me was the condition of the colored people, a great many of whom, like myself, had escaped thither as a refuge from the hunters of men. I found many, who had not been seven years out of their chains, living in finer houses, and evidently enjoying more of the comforts of life, than the average of slaveholders in Maryland…

…I visited the wharves, to take a view of the shipping. Here I found myself surrounded with the strongest proofs of wealth… I saw no whipping of men; but all seemed to go smoothly on.

Emphasis mine. Even under the worst conditions, humans have a tendency to fear escaping the control of overbearing government programs, and believe that however preferable freedom may be, it remains an inferior state when compared to servility.

The most horrible thing was that all of that violence served upon slaves was nothing to freedom. Echoing Henry Grady Weaver, Douglass writes that even progress itself was forbidden in the south if it came from workers who were slaves. The punishment for progress was whipping:

Does he [the slave] ever venture to suggest a different mode of doing things from that pointed out by his master? He is indeed presumptuous, and getting above himself; and nothing less than a flogging will do for him.

What ultimately freed Douglass, my friends on Goodreads will be happy to know, was the desire to read. At one point, he is on loan to a couple in Baltimore; the woman begins to teach him to read, but the man berates her, as reading can lead to only one thing: a desire for freedom.

It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things… I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty—to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom… I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read.

What would Douglass think today about schools and politicians prioritizing social promotion over learning, especially among minorities?

I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason. He must be able to detect no inconsistencies in slavery; he must be made to feel that slavery is right; and he can be brought to that only when he ceases to be a man.

In fact, it was the slave-owners who were “nice” who instilled in him the desire to be free. At one point, he is on loan to a relatively nice couple in Baltimore (he often had more to eat than white children in the area, and used that to trade for favors); the woman begins to teach him to read, but the man berated her, telling her, in front of Douglass, that reading could lead to only one thing: a desire for freedom.

These words sank deep into my heart, stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought.

From then on, he noticed that whenever his condition improved, “instead of its increasing my contentment, it only increased my desire to be free”.

Contented slaves require a level of moral and intellectual impoverishment that must be enforced by slave-masters.

Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave

If you enjoyed Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave…

For more about abolition, you might also be interested in The Star-Spangled Banner in MIDI and I have read a fiery gospel.

For more about education, you might also be interested in Brainwashing 101, Cell phone neo-McCarthyism, The Washington, DC Prison Experiment, Can schools compete with the Internet by clicking?, D.C. voucher students show gains, Maintaining Educational Diversity, No room for education reform in spending frenzy, Blogs fight resegregation in DC?, Stupid in America?, The basement was my university, Government food courts, ACLU enables Texas textbook takeover, Teaching kids to fail, Cell phones: threat to public safety, and Another reason to ban cell phones from schools.

For more about family, you might also be interested in What is the state’s role in marriage and the family?.

For more about slavery, you might also be interested in The last time an actor assassinated a president?, Slavery does not create wealth, The Life and Writings of Abraham Lincoln, The Life of Stephen A. Douglas, and Senator Kamala Harris calls for slavery reparations.

acting white

- No, ‘Acting White’ Has Not Been Debunked: John McWhorter

- “Research confirms that the ‘acting white’ charge is a real problem that intimidates some black students. Our job is to confront it.”

- ‘Acting white’ and being black?: Crystal Wright at CNN

- “More recently, my blackness was questioned by Keli Goff during an appearance on CNN last week. The two of us were discussing the illegal immigration crisis and Goff didn't like the argument I made. So she tried to insult me.”

bad luck

- The Case for Democracy

- When did America forget that it’s America?

- The Mainspring of Human Progress: Henry Grady Weaver at Internet Archive

- “For 60 known centuries, this planet that we call Earth has been inhabited by human beings not much different from ourselves… But down through the ages, most human beings have gone hungry, and many have always starved… The Roman Empire collapsed in famine. The French were dying of hunger when Thomas Jefferson was President of the United States. As late as 1846, the Irish were starving to death; and no one was particularly surprised because famines in the Old World were the rule rather than the exception… Hunger has always been normal… Down through the ages, countless millions, struggling unsuccessfully to keep bare life in wretched bodies, have died young in misery and squalor. Then suddenly, in one spot on this planet, people eat so abundantly that the pangs of hunger are forgotten.”

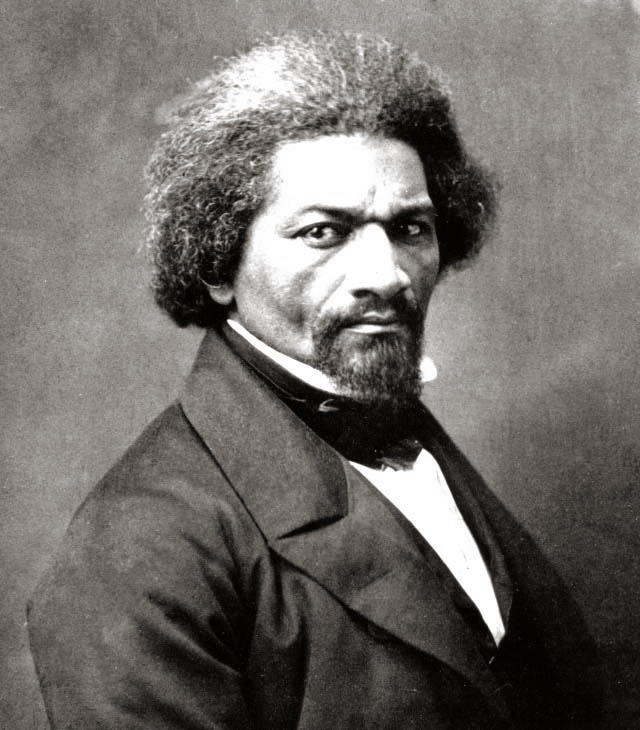

Frederick Douglass

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass•: Frederick Douglass (paperback)

- “Former slave, impassioned abolitionist, brilliant writer, newspaper editor and eloquent orator whose speeches fired the abolitionist cause, Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) led an astounding life.”

- Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave: Frederick Douglass at Internet Archive

- Frederick Douglass's amazing autobiography of his time as a slave, and his immediate experiences after leaving slavery.

- Frederick Douglass at Wikipedia

- “Frederick Douglass was an African-American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement from Massachusetts and New York, gaining note for his dazzling oratory.”

soft bigotry

- The Crushing Racism of Low Expectations: Liz Peek

- “Only 15 percent of black kids were deemed proficient in math, while 60 percent of Asians and 38 percent of whites made the cut. It begs saying that results across the board are appalling; but that less than one in five black kids can read or write with any fluency is truly criminal.”

- Oregon school district spends big on controversial ‘white privilege’ teacher training: Steve Gunn

- “The ‘white privilege’ crowd claims that fundamental ideals of American society, like hard work for personal gain and personal ownership of property, are products of white culture and completely foreign to black students. That means schools that try to prepare black children for success in the American free market economy are spinning their wheels, because black culture is collectivist in nature. The obvious political message is that black kids will only thrive in a socialist economy.”

- St. Louis schools taking aim at social promotion: Elisa Crouch

- “In the St. Louis area, 1,897 fourth-graders scored below basic on the state’s reading exam. Yet just 60 were forced to repeat fourth grade this fall, according to state retention data. No students at any grade level were held back at 274 area schools.”

“I will give Mr. Freeland the credit of being the best master I ever had, till I became my own master.”