Omni welcomes the eighties

I’ve managed to acquire a few caches of early OMNI magazines, and recently read the February, March, and April 1980 issues. With a likely three-month lead time to publication, the essays and editorials in these issues would have been written in November or so through January. That is, at the very end of the seventies and the height of seventies malaise. President Carter was still president. While the Iranian hostage crisis was weighing on his presidency, there was as yet no obvious alternative to Carter in the Republican Party.

On January 1, 1980, Carter seemed more vulnerable from an opponent in his own party—Ted Kennedy—than from any Republican. President Reagan wouldn’t even start showing his strength in the Republican primaries until March. Like President Trump in 2016, candidacy would be treated as a joke until it wasn’t.

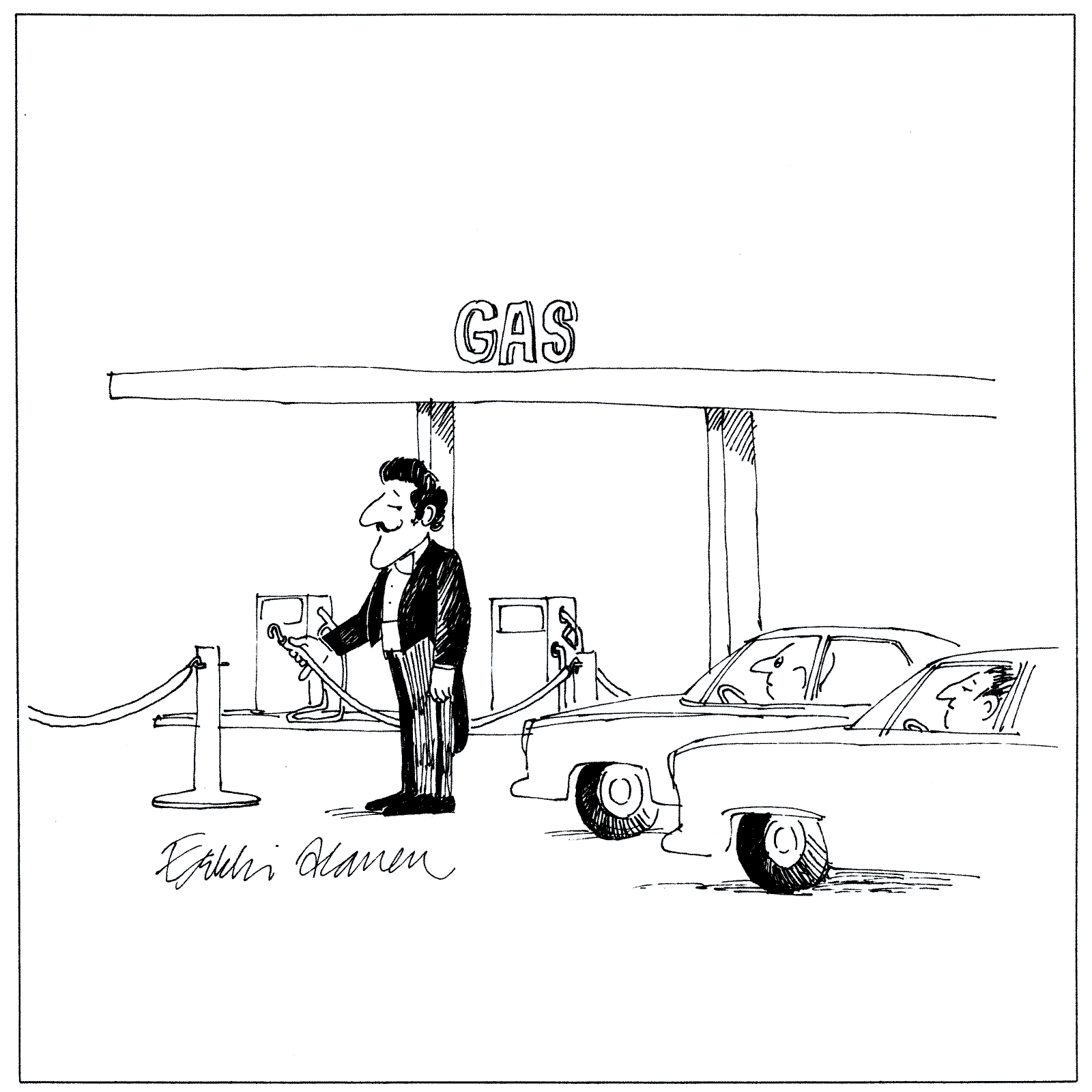

Emblematic of the era is a cartoon in the February issue showing a maitre’d controlling entry to a gas station. Under rationing and price controls, being able to both afford gas and have time to access it was becoming a class marker. That America was entering a period of decline was a widely spoken mantra in the beltway, and would continue to be until President Reagan’s new policies started taking effect in 1981 and 1982.

Most people in publishing and politics thought higher prices and higher unemployment—stagflation—was America’s inevitable future. They had no idea everything would change in just over one year when gasoline price controls would be rescinded and gasoline prices—along with prices for everything that relies on gasoline—would drop.

Tying into this seventies malaise was another surprise for me: a Thomas Szasz-like rant about the psychiatric industry that opened February’s “Continuum”1—and seeing by the signature at the end that it was in fact written by Szasz! Everybody wrote for Omni. As I recall from reading one or two of his books, Szasz had a lot of very good points—obscured by a near-complete rejection of potential physical causes for mental issues.

Unable or unwilling to bear the inexorable tragedies of the human condition, people now seek solace in the utopian claims of psychiatry concerning the causes and cures of everything “bad” the human heart is heir to.

In retrospect, Thomas Szasz’s complaints about the medicalization of human anxiety were as much a product of seventies malaise as they were predictive of the future. But despite the rebirth of American greatness in the eighties, the tendency to treat the normal human condition as if it were a disease requiring medication never went away. It continues today even in grade schools.

I almost certainly read the April issue back in the day. April’s “Continuum” contains two of the oldest items in my quotefile (a file that also contains a lot of Thomas Szasz). I started that list—in a paper notebook—because of Omni. I started it to remember the best quotes from “Continuum”. These were the first two, taken from the April issue:

Sometimes I think we’re alone. Sometimes I think we’re not. In either case, the thought is quite staggering. — R. Buckminster Fuller

There’s a hell of a good universe next door. Let’s go. — e.e. cummings

One of Omni’s specialties was complaining about the decline in space exploration and space exploration funding. That continues in these issues. Among these complaints there’s a shocking, in retrospect, note in February’s “Continuum”:

Now under development is a backpack space-walking device… currently receiving added attention because of serious problems with the space shuttle, much to the embarrassment of NASA. Concern has been raised that fragile, heat-resistant tiles, permitting a safe fiery shuttle reentry could be jarred loose or be damaged during blastoff…

Of course, being able to fix damage doesn’t matter if no one notices the damage until after catastrophic re-entry as would happen two decades later with Columbia.

The worst part about reading Omni’s justifiably pessimistic takes on the space industry isn’t the pessimism. It’s the optimism that went nowhere—fast. Robert L. Forward’s “Comet Catcher” describes a “general-purpose solar-electric-propulsion system” which would, among other missions, power a visit to the asteroids:

A visit to six asteroids forms the basis of the multiple-asteroid-rendezvous mission, planned for late 1988. The spacecraft will stop to explore for two months at each of six asteroids: Medusa, Nyssa, Erigone, Masallia, Mimosa, and finally Protogenia in 1999. Completion of this mission will take us into the twenty-first century, when the first manned missions to the outermost planets will begin.

By press-time the electric propulsion system powering that mission had already been cancelled. Technically, we still have a lot of time in “the twenty-first century” for “the first manned missions to the outermost planets” to begin. But those plans required manned missions to the innermost planets before the twenty-first century. That is, we should have had men on Mars more than a quarter century ago.

There’s also a Heinlein interview reprinting his congressional testimony on how the space program benefited the aged and handicapped. Heinlein highlighted spin-off technologies that helped him overcome a recent “transient ischemic attack”. More interesting than the spinoffs is his characterization of America’s space program:

Our race will spread out through space—unlimited room, unlimited energy, unlimited wealth. This is certain. But I am not certain the working language will be English. The people of the United States… have suffered a loss of nerve.

Both in our exploration of the stars and our disdain of the human condition, we’ve never fully recovered from the malaise of the seventies.

March computer ads in page order

One place where we—or a subset of us that included myself–were in full exuberance as we entered the eighties was the personal computer revolution, a wild and crazy frontier at the turn of the decade. This is where I came in, with a TRS-80 Model I purchased used in the summer of 1980. It kept me up late in high school and college programming games as well as tools to help me work.

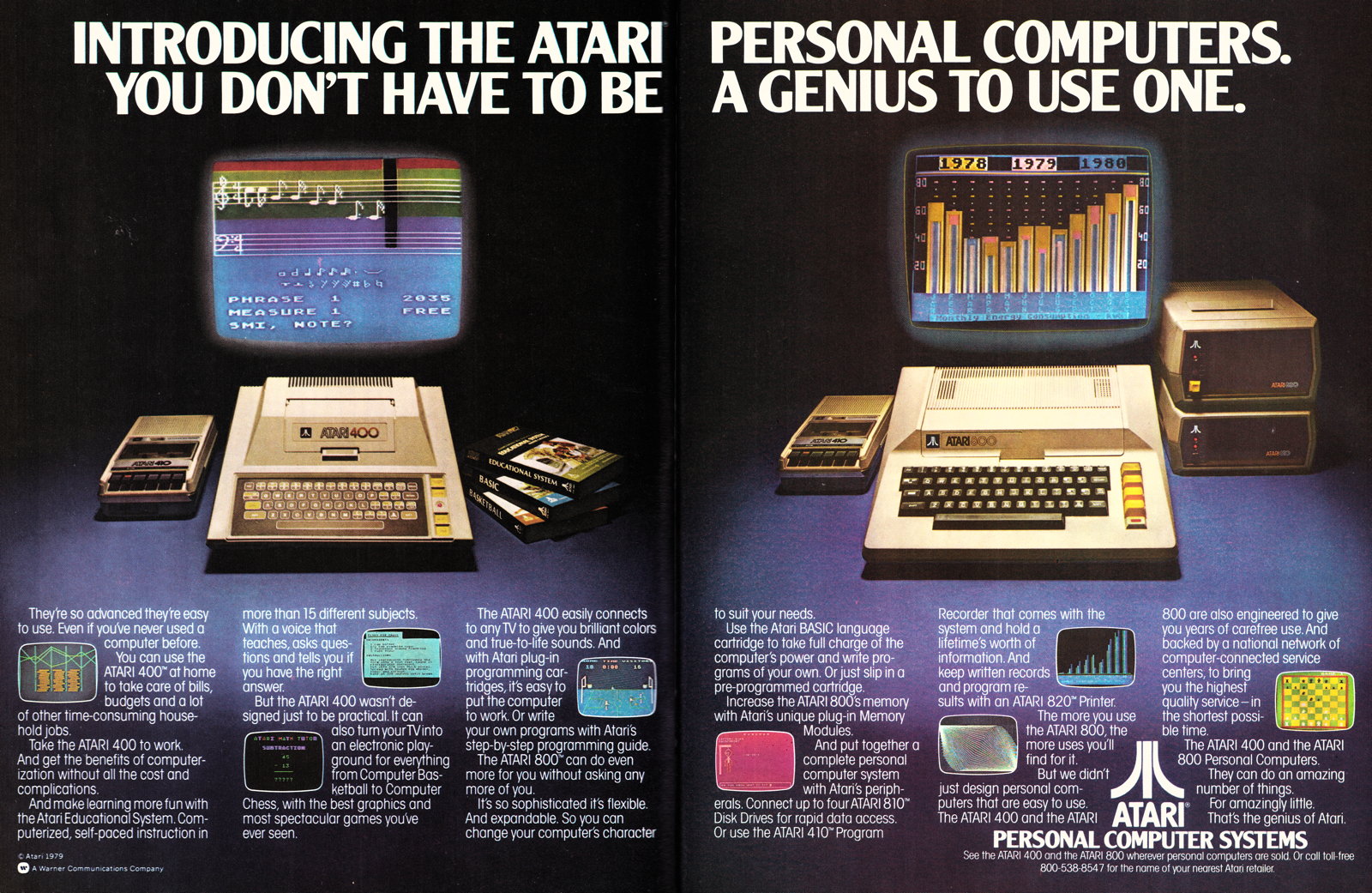

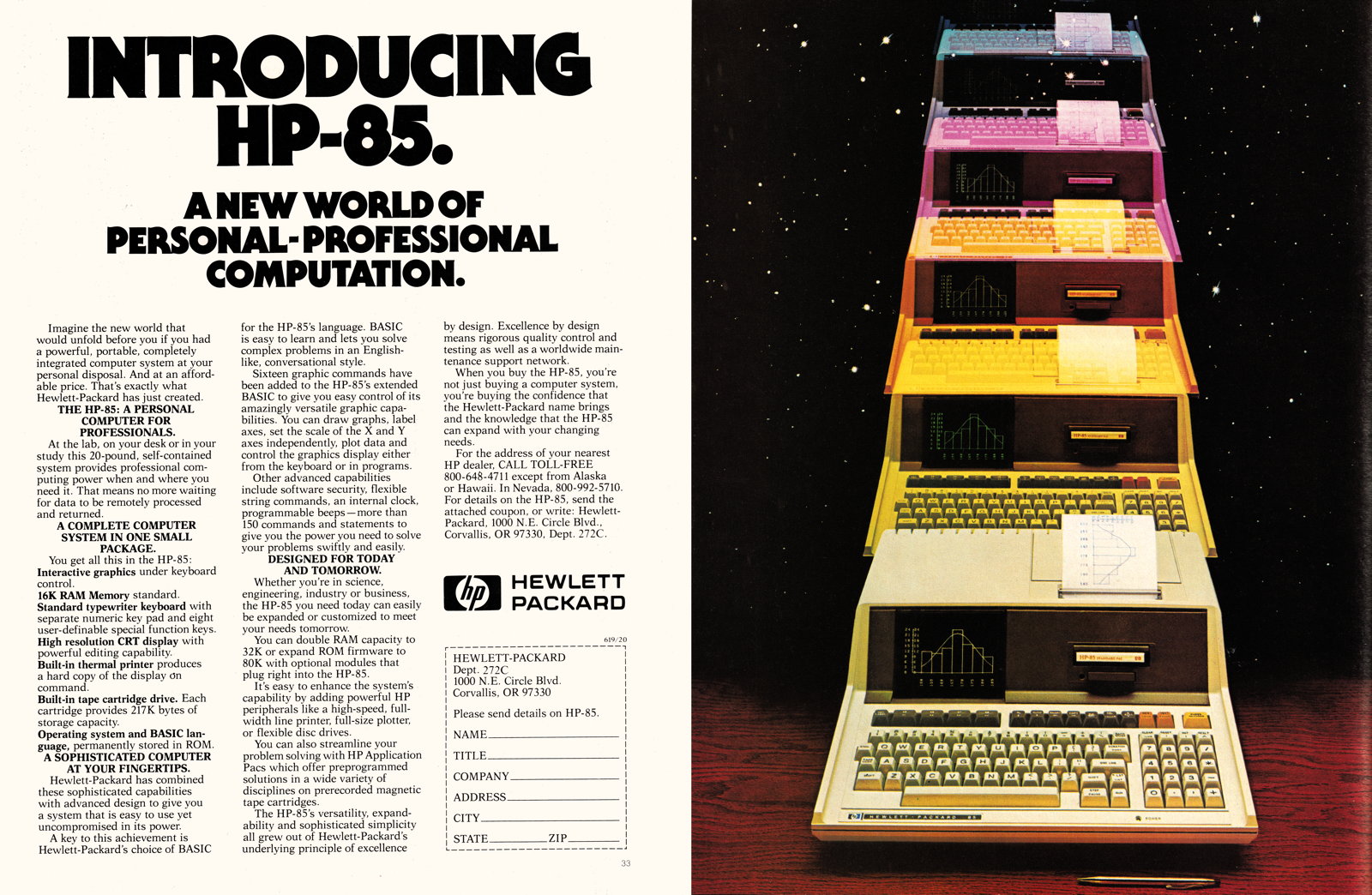

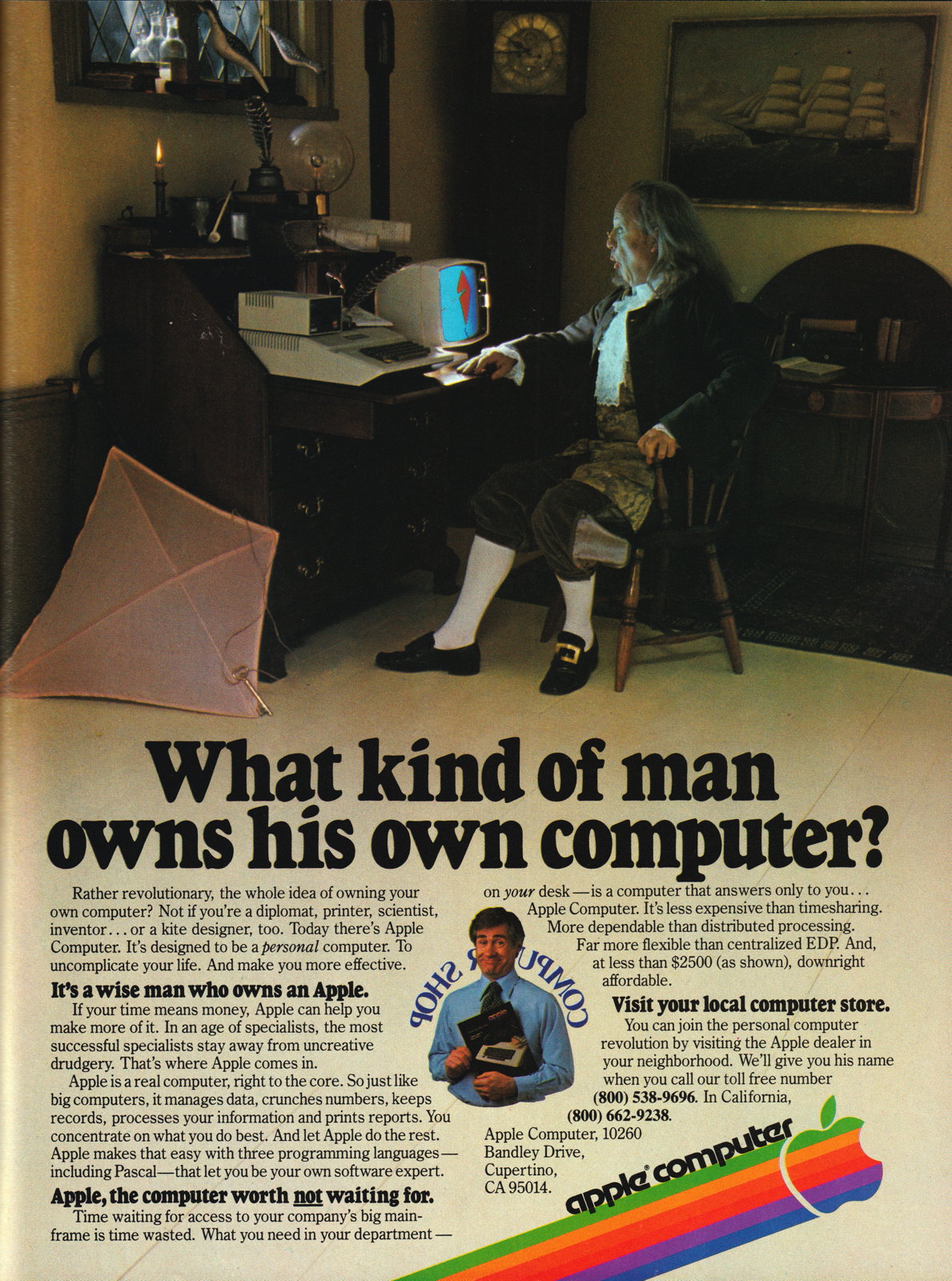

March contained several large personal computer ads. There’s a double-page spread for the Atari 400/800, an ad for the Hewlett Packard HP-85, a Motorola double-spread introducing the MC68000, and a full page Apple ad featuring Ben Franklin. Even Ohio Scientific has a small ad, albeit paired with a generic answering machine.

Did all of these ads happen to show up in the same issue, or did Omni contact a bunch of computer companies to let them know their competitors were buying space? There’s nothing particularly computer-themed about March. There were no such ads in February or April (or in January, or December of 1979).

“We’d never use computers to track your purchasing habits and show you ads based on what you’re talking about with friends.”

While Motorola had an ad in January, it didn’t mention any specific product. The only personal computing ad in April is a half-page for onComputing magazine. The issue pictured in onComputing’s ad featured Jerry Pournelle on the cover. There’s also an IBM ad, but focused on mainframes and business networks, not personal computing. IBM wouldn’t be introducing their personal computer until August 12 1981. It was almost two years away.

Given Frank Herbert’s tirade in the same issue—reminiscent of Ted Nelson—about how you should own a computer because the government and businesses are using them against you, it’s interesting that the IBM ad focuses on how business data retention is safe for consumers.

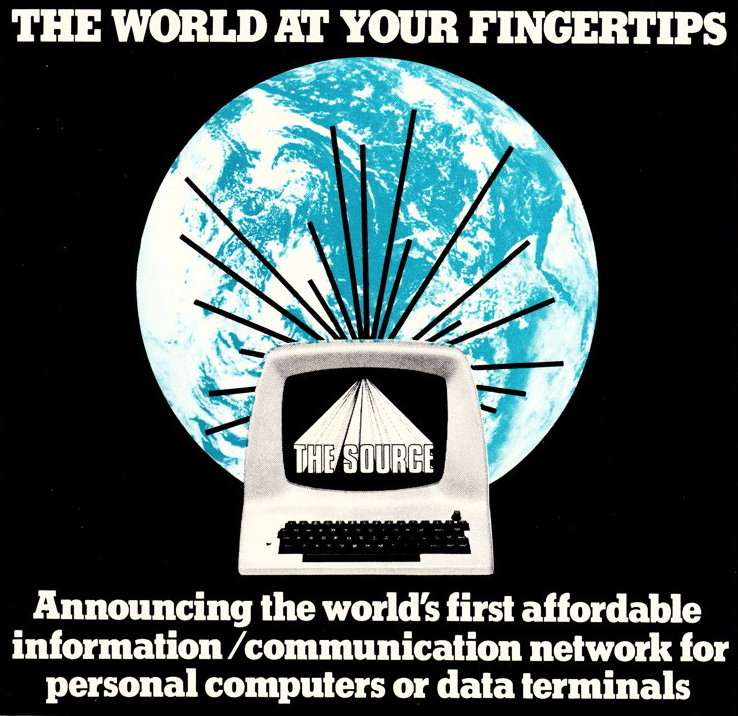

Another computer-oriented harbinger of the future in March is an ad for The Source, “THE WORLD AT YOUR FINGERTIPS”:

Announcing the world’s first affordable information/communication network for personal computers or data terminals.

Besides advertising access to sources such as the NYSE and UPI, it also advertised technical features:

THE SOURCE supplements your personal computer with unlimited mainframe storage capacity and complete editing, and debugging systems… plus programming in several languages including EXTENDED BASIC, FORTRAN, RPG II, and COBOL.

While those languages might not seem important today, three of them were among the most used languages of the era, in home computing (BASIC), scientific computing (FORTRAN), and business computing (COBOL).

All for “charges as low as $2.75 per connect hour (non-prime time), accessed through a local telephone call.” It was important that it be a local call, because long distance was still very expensive.

While we were still over a decade away from a public Internet2, connectivity was definitely on the rise, and it was obvious that computer-to-computer connectivity was going to replace both letters and telephones. All of which is a long introduction to Mark R. Chartrand’s March “Space” column predicting wrist radios within a decade, because:

Instead of making [satellites] heavy, with redundant circuitry, we can cram into them more power, larger antennas, more circuits. We no longer have to make them failure-proof: We can send a technician to fix satellites that go haywire. Because of this, the Dick Tracy wrist radio may be a reality by the end of the 1980s.

Building on local bulletin board systems, The SOURCE pioneered nationwide computer to computer communication.

So right and so wrong at the same time, demonstrating February interviewee Arno Penzias’s point that “Predicting is always a risky business”. While improving satellite technology certainly had a lot to do with the coming proliferation of cell phones, technicians in space were not the reason. Even now, almost half a century later, we aren’t sending technicians to fix communication satellites. Unlike technicians, satellites are mostly disposable, something that could have been predictable from the trends Chartrand used: the reduction in size and cost, and the increasing standardization, of the parts that go into making them.

The cost of sending up a technician vastly exceeds the cost of sending up a replacement satellite. As I write this in early May, SpaceX has already deployed 67 satellites in 2025. The Starlink system alone had 7,135 satellites in orbit as of March; “only” 7,105 were operational.

Arno Penzias’s full quote was that “Predicting is always a risky business, because if you had any clear idea of what lies beyond, you’d be working with it already.” Penzias is one of the cosmic-background discoverers. He also took on the educational system somewhat obliquely, asking why curiosity disappears from older children.

The question shouldn’t be “What makes me curious about that?” It should be “Why isn’t everybody curious about it?”

Theodore Sturgeon took on both instant communications networks and a specific kind of lack of curiosity among the elite in “Why Dolphins Don’t Bite”, a two-parter across February and March. Dolphins is a two-edged sword sort of a story. The initial perspective has the main character unwilling to accept the horrors necessary for universal instantaneous communication, horrors that as far as the rest of the universe are concerned are only horrific to provincial earthlings.

But it turns out that the atrocities that the entire universe, including the titular dolphins, have for eons been committing in exchange for their advanced communications network were completely unnecessary. All they needed to do was develop more humane technology, technology so easy that even a non-specialist could discover it once they knew such communication was possible.

All they had to do was look.

Curiosity about why something works is as important as that it works. And it’s important not just for effectiveness but for ethics. Too many times, people in power seem to be not just not curious, but actively anti-curious, about tradeoffs that aren’t even necessary between progress and saving lives. It’s a callousness about human life that seems almost strategic in its specificity.

My expectation is that the sky will fall. My faith is that there’s another sky behind it. — Stewart Brand (Omni, December 1979)

“Continuum” was Omni’s list of futuristic news factoids. It was always preceded by a guest editorial.

↑Until the World Wide Web went public in 1993, the Internet that the public saw was little more than another, if bigger, bulletin board system.

↑

excellence

- Natural monopolies: a 20-minute call for $8.83

- “A 20-minute call anywhere in the country will cost me only $3.33? What’s the catch?” The catch is that those are still outrageous monopolistic prices.

- Reagan’s Lincolnian Revolution

- Reagan provided an alternative to the assumption held by both parties that bureaucracy was superior to individual freedom.

- Starlink satellites: Facts, tracking and impact on astronomy: Tereza Pultarova, Adam Mann, and Daisy Dobrijevic

- “Are Starlink satellites a grand innovation or an astronomical menace?”

programming for all

- 42 Astoundingly Useful Scripts and Automations for the Macintosh

- MacOS uses Perl, Python, AppleScript, and Automator and you can write scripts in all of these. Build a talking alarm. Roll dice. Preflight your social media comments. Play music and create ASCII art. Get your retro on and bring your Macintosh into the world of tomorrow with 42 Astoundingly Useful Scripts and Automations for the Macintosh!

- Baseball in the rain

- In 1980, after I bought a personal computer, I wrote a simple computer program in BASIC and sold it to one of the many magazines at the time. To the second-major newspaper of the area, this was a big deal.

- Review: Computer Lib: Jerry Stratton at Jerry@Goodreads

- Rambling and incoherent by design, Nelson is adamant that computers should not be the domain of a technological elite.

- Tandy Assembly 2018

- Tandy Assembly was earlier this November, and I have never seen so many Radio Shack computers in one spot. Also, my love affair with daisy wheels is rekindled.

therapeutic state

- Ceremonial Chemistry

- Thomas Szasz subtitled this “The Ritual Persecution of Drugs, Addicts, and Pushers”. It’s a brilliant piece of work drawing on history from as far back as the witch trials and persecution of Jews. His thesis is that mankind requires scapegoats on a ritual scale. While hardly a ground-breaking idea, the depth of his examination is.

- The Modern Lobotomy: Whitewashing Child Mutilation

- Child mutilation in the service of gender quackery is something that future generations will look back on in horror, much as we today look back on the lobotomy.

- Why Dolphins Don’t Bite: Theodore Sturgeon

- “Dom Felix invented the Receiver. So say the almanacs. So say the encyclopedias, the infobanks, the students.”

More abortion

- My Car My Abortion

- “Let me drink and drive.”

- The universality of life in stories

- Evil doesn’t win by being evil. It wins by convincing us that it is virtuous. Pregnant women know, instinctively, that they are carrying a child. But we have allowed ourselves to be convinced as a society that they are wrong.

- Kirk Watson emerges from cave after 200 years of isolation

- Former Austin mayor confused, faint because of new laws that presume adults are children.

- Planned Parenthood announces baby delivery service

- The non-profit plans to compete with market leaders on speed, quality, and taste, to bring healthier, happier babies to a new convenience demographic.

- San Diego Pro-Choice and the Meaning of Life

- San Diego pro-abortion activists such as Canvas for a Cause and San Diego’s Radical Feminists of Occupy San Diego are protesting a San Diego Catholic organization that, in their words, “exists to prevent women from getting abortions”.

More computer history

- Creative Computing and BASIC Computer Games in public domain

- David Ahl, editor of Creative Computing and of various BASIC Computer Games books, has released these works into the public domain.

- Hobby Computer Handbook: From 1979 to 1981

- Hobby Computer Handbook lived for four issues, from 1979 to 1981. Back in 1979 and 1980, I bought the middle two issues. I’ve recently had the opportunity to buy and read the bookend issues.

- Hobby Computer Handbook

- Hobby Computer Handbook was a short-lived relic of the early home computer era, an annual (or so) publication of Elementary Electronics.

- 8 (bit) Days of Christmas: Day 11 (O Christmas Tree)

- Day 11 of the 8 (bit) days of Christmas is the graphic accompaniment to “O Tannenbaum” from Robert T. Rogers “Holly Jolly Holidays”, from December 1984.

- 8 (bit) Days of Christmas: Day 100 (Hearth)

- Lower resolution graphics were more appropriate for animation, because you could page through up to eight screens like a flip book. This is Eugene Vasconi’s Holiday Hearth from December 1986.

- Seven more pages with the topic computer history, and other related pages

More eighties

- Hesperia Class of ’82

- The 40th reunion for the Hesperia High School Class of 1982 is July 15 through July 17, 2022. We look forward to seeing you!

- Hobby Computer Handbook: From 1979 to 1981

- Hobby Computer Handbook lived for four issues, from 1979 to 1981. Back in 1979 and 1980, I bought the middle two issues. I’ve recently had the opportunity to buy and read the bookend issues.

- Nothing will be restrained from them, which they imagine to do

- Figuring out stuff from “the times before” is hard to do.

More Jimmy Carter

- Election lessons: be careful what you wish for

- Republicans should learn from the Democrats’ mistake of the primary season: be careful what you wish for, you might just get… half of it. They wanted Donald Trump as Hillary Clinton’s opponent.

More OMNI Magazine

- Power Play 2020

- Frederik Pohl shows why science fiction authors aren’t any better at being futurists than anyone else. Hubris is a powerful drug.

- Better for being ridden: the eternal lie of the anointed

- Whenever there’s a crisis, politicians and the media always tell us that if we do what they say, we’ll be all right. This is always a lie. And however often they fail and however many die from their ministrations, their wabbling fingers always return to the mire.

- The Best of Omni Science Fiction No. 2

- I always enjoyed Omni, but, unlike its sister publication, I enjoyed it for its photos more than for the stories. Its best, however, was not too bad, at least from 1978-1980.

- Omni’s Jobs of the Future from 1985

- What Omni’s popular science writers saw as the jobs of tomorrow thirty years ago.

More seventies

- Plain & Fancy in the seventies with Hiram Walker

- Enjoy a whole new world of fun, excitement and discovery in Hiram Walker Cordials, adding a personal touch to all your memorable moments and special occasions—plain or fancy!

- A Bicentennial Meal for the Sestercentennial

- Four community cookbooks celebrating the bicentennial. As we approach our sestercentennial in 2026, what makes a meal from 1976?

- A golden harvest of sunflower seeds

- Golden Harvest Sunflower Seed Recipes is a fascinating bit of ephemera from the seventies and the tail end of the era of regional whole grain mills.

- Hesperia Class of ’82

- The 40th reunion for the Hesperia High School Class of 1982 is July 15 through July 17, 2022. We look forward to seeing you!

- Hobby Computer Handbook: From 1979 to 1981

- Hobby Computer Handbook lived for four issues, from 1979 to 1981. Back in 1979 and 1980, I bought the middle two issues. I’ve recently had the opportunity to buy and read the bookend issues.

- Seven more pages with the topic seventies, and other related pages